Insight

October 29, 2020

Naturalizations for Non-Citizens in Military Service

Executive Summary

- Since the Revolutionary War, non-citizens have served a vital role in the U.S. military by helping to meet recruitment goals and by bringing necessary skills.

- The number of naturalizations for non-citizen members of the armed services has fallen every year since the beginning of the Trump Administration due to increased regulation on immigration and restrictions on non-citizens in the armed forces.

- With the cost of becoming a U.S. citizen rising, immigration reform and reintroducing programs such as the Military Accession Vital to National Interest program or the Naturalization at Basic Training Initiative could incentivize non-citizens to join the U.S. Armed Forces, which ultimately would contribute to national security and the goals of the U.S. military.

Introduction

The naturalization rate for non-citizen service members has fallen substantially during the Trump Administration, dropping 43 percent in 2018 from 2017. Over 760,000 non-citizens have gained U.S. citizenship through military service in the past century. In addition to providing sheer numbers to the country’s military, non-citizens encompass skills that are highly valuable to the national interest. The U.S. government should consider streamlining the naturalization process via military service as a way to diversify and enhance the armed forces. With the cost of becoming a U.S. citizen rising, as fees increased by 83 percent this year, naturalization via military service provides an alternate path to citizenship for non-citizens, while the military benefits from the range of skills non-citizens bring.

Naturalization Through Military Service and Its Recent History

Non-citizens have served in the U.S. Armed Forces since the Revolutionary War. Each year, around 24,000 non-citizens actively serve in the military and 5,000 join. In 2018, the Philippines and Mexico were the two largest countries of origin for non-citizen U.S. military personnel. Historically, other top countries of origin for non-citizen service members include Jamaica, Korea, and the Dominican Republic.

Since the founding of the United States, many non-citizens have used the military as an avenue to obtain expedited citizenship. Encouraging non-citizens to enter the military by offering them expedited citizenship gives the military access to a broader pool of soldiers and more skills.

Immigration and Nationality Act

Non-citizens who serve in the U.S. Armed Forces can expedite the naturalization process and waive certain naturalization requirements under Sections 328 and 329 of the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). Non-citizens can start the naturalization process after one year of honorable service during peacetime through Section 328, or immediately if serving actively during a designated period of hostility through Section 329. Naturalizations via military service are highest during times of war. During World Wars I and II, 143,000 non-citizen military personnel were immediately naturalized, and 31,000 were naturalized during the Korean War.

Since the INA, the number of non-citizens naturalized via service in the armed forces has fluctuated depending on whether it is a time of war or peace, but also as programs and policies have changed to incentivize or disincentivize the service of non-citizens.

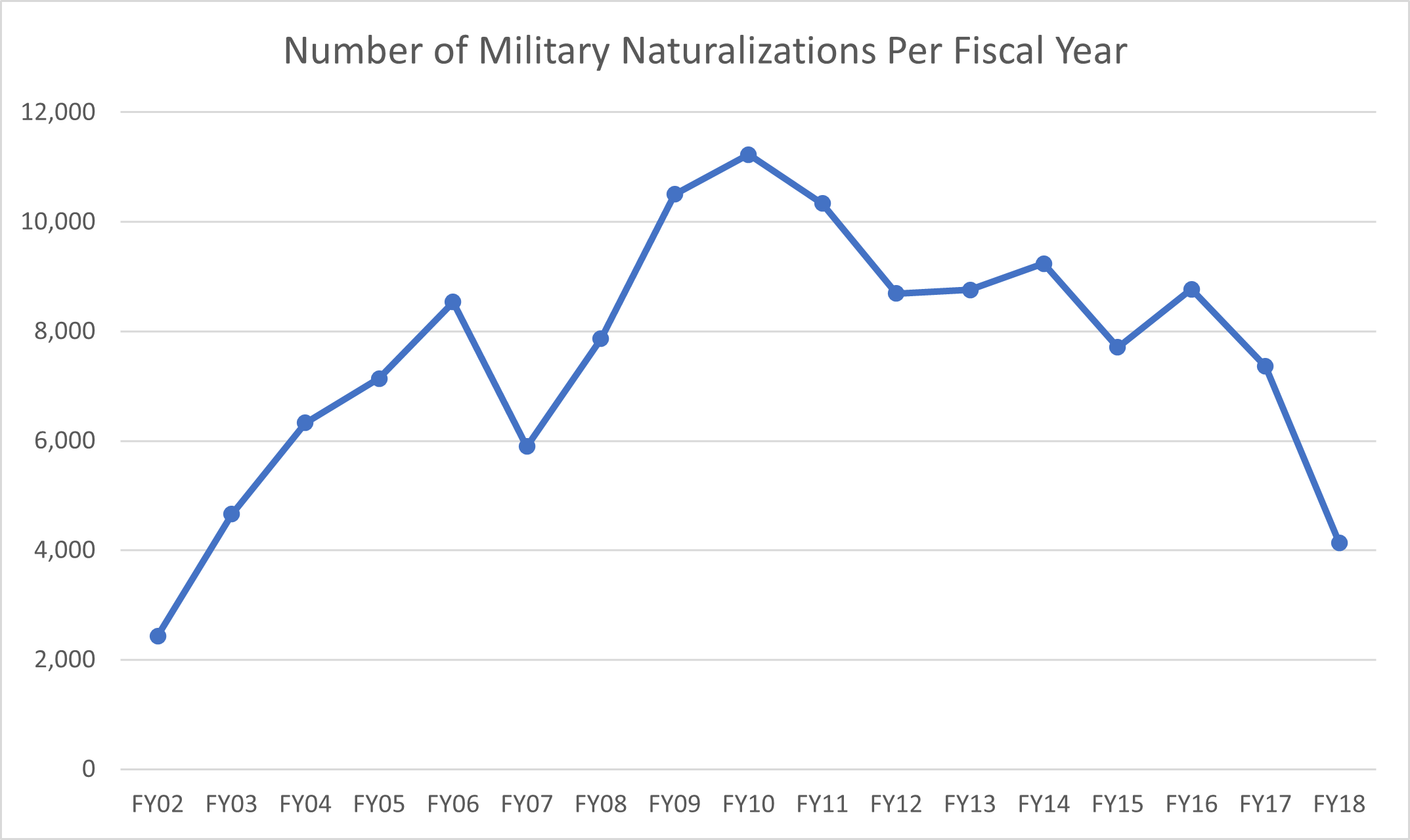

The latest data from 2018, show that 4,135 service members were naturalized that year, down 43 percent from 2017. 2018 saw the lowest number of naturalizations since 2002, when 2,434 service members were naturalized. In 2010, United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) completed 11,230 military naturalizations, the highest rate in history.

Chart 1

Data from USCIS naturalization statistics

Shifting Policies Under the Trump Administration

Under the Trump Administration, the Department of Homeland Security and the Department of Defense (DOD) have implemented a series of new policies that have created barriers for non-citizens to gain citizenship via military service, and these changes could be reasons why less service members are applying to naturalize—an indication that the pathway is becoming more cumbersome and less attractive.

In 2017, Defense Secretary Jim Mattis added more background checks for non-citizens and implemented mandatory wait times before the DOD could issue “honorable service” paperwork that non-citizens must have in order to apply for citizenship. After this came out, the number of applications dropped to 1,069 for the first quarter of 2018, down from 3,132 in the last quarter of 2017. This policy was ultimately ruled illegal in 2020.

In 2018, USCIS terminated the Naturalization at Basic Training Initiative, which provided onsite immigration resources and staff to support recruits beginning the naturalization process. USCIS also shut down 19 of its 23 field offices abroad in 2019, complicating the naturalization process for many service members abroad.

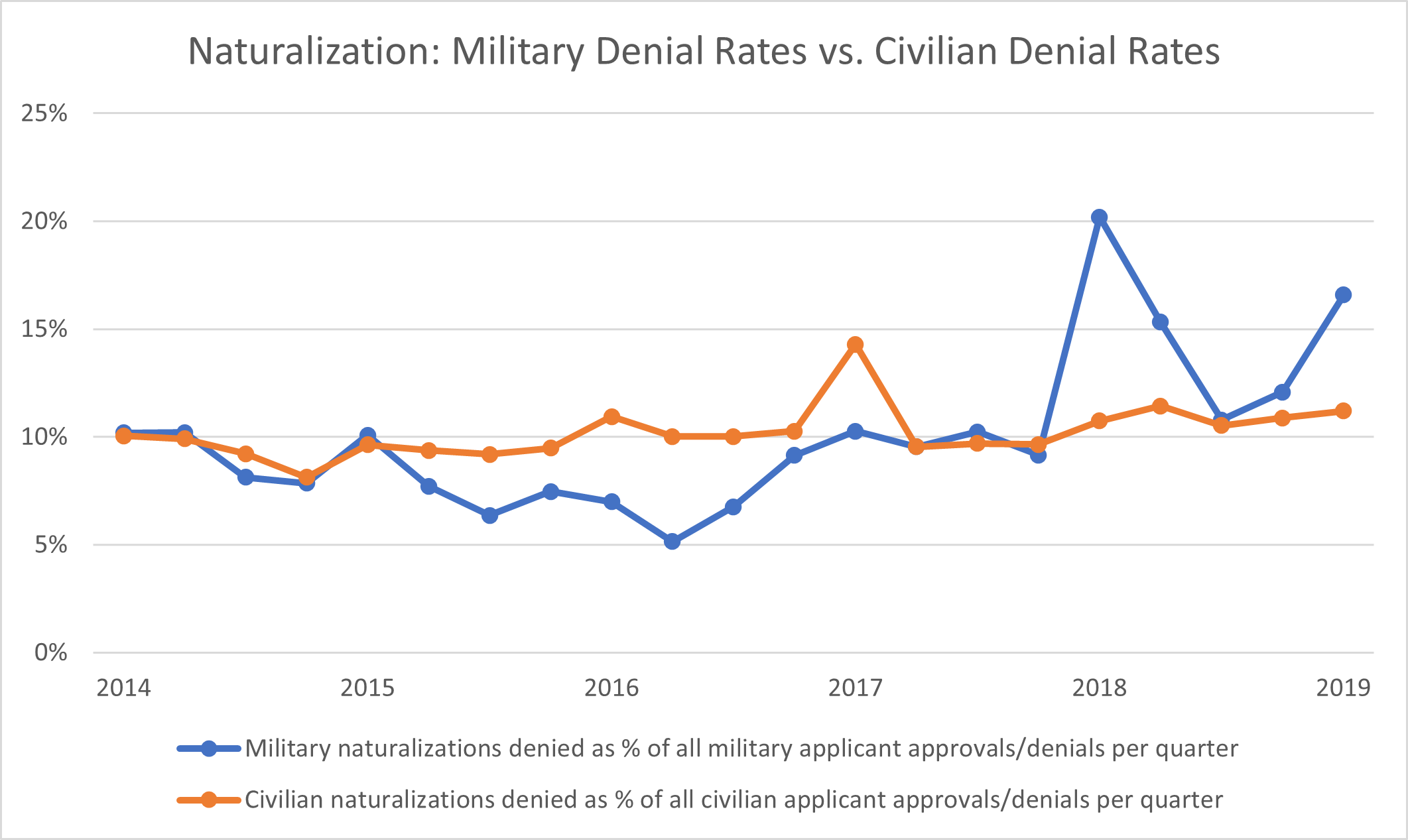

For those who finish the naturalization application through section 328 or 329 in the INA, approval is not always guaranteed. In fact, USCIS has denied military naturalization applications at a higher rate than civilian applications for every quarter since the beginning of fiscal year (FY) 2018. See Chart 2 for an illustration of military denial rates compared to civilian denial rates.

Chart 2

Data from USCIS Number of N-400 Applications for Naturalization

Under the Trump Administration, as a result of more relegation placed on the naturalization via service process, it has been found that civilian applications are approved far more frequently than military applications. To naturalize via service, a non-citizen service member must be found to be “honorable,” and this is determined by branch of the U.S. Armed Forces in which the person is serving. “Honorable” service can be proved by the statements written on a Form N-426, where a representative from the branch must certify it. The DOD, however, has changed the rule regarding who can certify the form for a non-citizen: The DOD now requires a colonel or Navy captain to certify the form. With a small pool of colonels and Navy captains, it makes it much hard for non-citizens to be certified “honorable.” Civilians obviously do not have any similar hurdle.

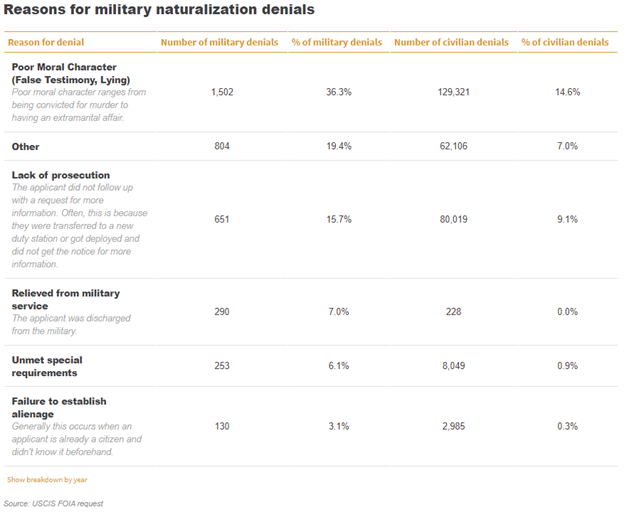

There are several reasons why a military application could be denied in general (see Chart 3). The main reason for denial is that a service member may not be found to possess “good moral character.” Under current law, honorable service does not prove good moral character, and even having a minor offense on one’s record could categorize a non-citizen as having poor moral character. Of note, 36 percent of the 4,137 denials of military naturalization applications in 2015 were denied because the service member lacked “good moral character,” whereas 15 percent of non-military naturalization applications were denied for the same reasoning in the same year. The difference in military denials versus nonmilitary denials likely reflects the degree to which military personnel struggle with addiction and violence.

Another main reason for military denials is “failure to prosecute” (i.e. did not follow up on) an incomplete application, even if due to deployment. In fact, in 2016, about 16 percent of military naturalization applications were denied for not following up on the applications, while only 9 percent of civilian applications were denied for the same reason.

Chart 3

Military Accessions Vital to the National Interests (MAVNI) Program

The INA is currently the only way to naturalize through military service. In the early 2000s, another program called Military Accessions Vital to the National Interests (MAVNI) was created to fill specific military shortages and meet general recruitment goals. Unlike the INA, MAVNI allowed certain non-citizens to gain citizenship without first having to go through the lengthy process of obtaining a green card. Around 10,400 non-citizens have enlisted through the program since its founding.

To enlist through this program, a non-citizen must have come to the United States (and stayed) legally for two years and proved that they are vital to the national interest. To prove this, an applicant would have to show that they had medical skills or critical language and cultural skills in the areas where the military was lacking. The U.S. government rewarded successful applicants with the promise of an expedited path to citizenship.

The Obama Administration added Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) recipients to the list of those eligible for the MAVNI program in 2014, and since then around 900 DACA recipients have taken advantage of the opportunity. After President Trump took office and due to the DACA addition, however, the military began requiring enhanced background screenings on MAVNI recruits because of perceived national security threats, and the DOD decided to stop enlisting non-citizens through the MAVNI program in October 2016.

By 2017, The Trump Administration had added additional background checks, and the remaining MAVNI recruits were not allowed to start basic training until their background checks were approved. These combined efforts have frozen the MAVNI program and created a backlog within the DOD. After 2017, the DOD decided to allow MAVNI recruits to finish their contracts, but to not renew MAVNI for future years.

Over 4,000 non-citizen recruits were left in limbo after the suspension of the program in 2017, with many falling out of legal status and faced with the risk of deportation. Still in 2020, some MAVNI recruits are still awaiting background check clearances to begin basic training.

Naturalization Fee Hikes

With naturalization fees increasing by 83 percent this year, the U.S. military may see an increase in demand for naturalization through military service. On July 31, 2020, the USCIS increased the fee to apply for citizenship through naturalization from $640 to $1,160 (if filed online) or $1,170 (if filed on paper). Those who naturalize through military service have their application fees waived. With an increase in application fees for naturalization, more non-citizens may be willing to enlist in the armed service to receive an expedited and cheaper way to citizenship.

Immigrants’ Contributions to the Armed Services

Though non-citizens account for a small percent of the U.S. Armed Forces, they are vital. The Center for Naval Analyses highlights three reasons why immigrants are important to the military: The number of recruitable non-citizens in the United States in the desired age range is quite large (approx. 1.2 million); immigrants possess skills critically needed in the armed forces; and non-citizen recruits have far lower attrition rates and are much less likely to leave before the end of their service.

These and other reasons are outlined below and suggest that the U.S. military would benefit from policies enabling expedited naturalization through military service.

Military Recruitment Goals and Retention

The U.S. military is struggling to meet its recruitment goals. For example, the army fell 10,000 recruits short of the 80,000 required in 2018. Roughly, 1.2 million green card holders met the baseline requirement for military service in 2011, and this does not include the non-citizens that would be eligible through MAVNI. In 2016, there was 690,000 non-citizens aged 18-24, the age range most likely to enlist, on temporary visas who met the requirements to enlist. By limiting green card holders’ entrance into military service, recruitment goals are not being met and critical skills remain in demand.

While serving, non-citizens bring a variety of necessary skills in fields other than medical, linguistics, and cultural, such as technology, engineering, and medicine. While they bring necessary skills, non-citizens also tend to perform better than citizens in the military. Data show that non-native born service members have lower rates of attrition than native-born service members. A 2011 CNA study found that 18.2 percent of non-citizens leave the military within four years, compared to 31.9 percent of citizens. Also, when surveyed, 50 percent of MAVNI recruits indicated they would like to remain enlisted until retirement. Non-citizen military personnel also tend to have higher educational levels than citizens and commonly outperform citizens when it comes to military testing.

Finally, the children of non-citizens may go on to contribute to the armed forces. According to a report from the National Immigration Forum, the net growth in the U.S. population of 18- to 29-years-olds, which is the segment of the population most likely to enlist, will come entirely from immigrants and children of immigrants. Historically, we have seen a trend in U.S.-born children of immigrants serving in the armed forces; almost 1.9 million veterans are the U.S.-born children of immigrants. Including the 2.4 million veterans of immigrant origin, 13 percent of all veterans are immigrants or the children of immigrants.

Language and Cultural Competency

Non-citizens often have critical skills such as deep understandings of the language and culture of regions where the United States is currently or could be engaged militarily. Language and cultural gaps in the military could pose a national security risk or at least make the work of these groups far less efficient and successful. In 2017, a Government Accountability Office report found that the DOD lacks sufficient foreign language proficiency, which has created a backlog in the translation of intelligence documents, hindering the U.S. military. MAVNI was created specifically to address and fill these languages and culture gaps in the U.S. military. When it was still an active program, MAVNI served as a way to bring native speakers with deep cultural understandings into the military. The termination of the program and the recent barriers placed on non-citizens entering or already in the military likely hinder the acquisition of cultural and language competencies that are necessary for creating a viable and effective military.

Conclusion

With the rising cost and stricter criteria for becoming a U.S. citizen through non-military avenues, non-citizens could be more inclined to join the armed services in order to naturalize. In the last several years, however, the discontinuation of MANVI and the Basic Training Initiative along with additional regulations surrounding non-citizens service members make it more challenging for non-citizens to naturalize via service. With so many obstacles and rising denials, the U.S. military could be forgoing an opportunity to enhance and diversify its skills. Reviving the MAVNI program and the Basic Training Initiative or creating other paths to citizenship through military service could result in a stronger military and streamlined immigration process that would benefit the non-citizens, their families, and the U.S. Armed Forces.