Research

May 19, 2016

Final Overtime Rule: Minimal Benefits and Major Costs

Overview

The Department of Labor’s (DOL) final overtime pay rule has been advertised as a substantial pay raise for millions of U.S. workers. However, a closer look at the rule reveals the worker benefits are quite limited and the regulatory costs on businesses are substantial. In particular:

- Only 825,000 of the 4.2 million newly covered workers would regularly benefit from the rule;

- For all 4.2 million newly covered workers, the net average weekly pay increase would be only $5.48, while for those who regularly work overtime, the increase would be a dismal $19.97; and

- Businesses would face nearly $3 billion in compliance costs and over 2.5 million paperwork burden hours.

Introduction

This week DOL released the final overtime pay rule.[1] The DOL’s final rule will raise the minimum weekly pay threshold legally required to exempt salaried workers from overtime pay from $455 per week to $913 per week. The rule has been met with much praise among labor advocates, who believe it to be a “major victory for working people.” A closer look at the regulation, however, reveals that the DOL itself believes that the new overtime pay protections will only have a limited impact on workers. For instance, while 4.2 million workers will now be eligible for overtime pay, fewer than a million of those employees regularly work more than 40 hours per week and would actually benefit from the rule. Meanwhile, it will also impose billions of dollars in regulatory compliance costs over the next decade.

How DOL is Adjusting Overtime Pay Requirements

Under DOL regulations, there are three primary requirements to exempt a worker from overtime pay: the worker must be salaried (the salary basis test), the salary must meet a minimum level (the salary level test), and the worker’s duties must align with the definition of an executive, administrator, or professional (EAP) employee (the duties test). In the regulation released this week, the DOL is expanding eligibility for overtime pay by adjusting the salary level test. In particular, it is raising the salary level requirement for both standard exemptions and highly compensated employees (HCE). DOL, meanwhile, did not make any changes to the duties test.

The increase in the salary level required for standard exemptions is the primary way DOL is expanding overtime pay coverage. Under the new rule, DOL will raise the weekly pay threshold required to exempt salaried workers from overtime pay from $455 per week or $23,660 per year (set in 2004) to the 40th percentile of earnings for full-time salaried workers in the lowest-wage Census Region, which is currently the South. This results in a new salary threshold of at least $913 per week or $47,476 per year. DOL will also begin automatically updating the salary threshold requirement every three years so that it remains fixed at the 40th percentile of weekly earnings in the lowest wage census region. The first update will occur at the beginning of 2020.

DOL is also adjusting the salary level required for the HCE exemption. The HCE exemption was introduced in 2004 and it imposes minimal duties requirements for employees who earn at least $100,000 per year. In the new regulation, the DOL will raise the HCE salary requirement to the 90th percentile of earnings of full-time salaried workers nationally, which is $134,004 per year. DOL will also update the HCE salary threshold every three years so it remains fixed at the 90th percentile.

Workers Impacted by the Rule Change

Of all of the changes imposed by the new regulation, the standard salary requirement (the increase from $455 to $913 per week) will have the largest impact on the workforce (the salary threshold increase for the HCE exemption only makes 64,900 workers eligible for overtime pay). Table 1 contains the DOL’s estimates for the number of workers who would be exempt from overtime pay under the current overtime rule, the number who will no longer be exempt because of the standard salary increase in the new overtime rule, and the total number who will actually benefit from the standard salary level increase.

|

Table 1: EAP Workers by Salary Level, 2017 |

|

| Worker Category |

Workers |

| Total EAP |

22,500,000 |

| EAP who earn between $455 and $913 per week |

4,163,000 |

| EAP who earn between $455 and $913 per week and work overtime |

825,000 |

DOL estimates that in 2017 there will be about 22.5 million workers who would qualify for an EAP exemption status under the current rule. That is, next year DOL expects there to be 22.5 million workers who earn over $455 per week and meet the duties requirements to be exempt as an EAP worker. About 4.2 million of those workers will earn between $455 and $913 per week and under the new rule will no longer be exempt from overtime pay. Most of those workers, however, will not benefit from the overtime pay rule. In particular, DOL estimates that only 825,000 workers who will no longer be exempt from overtime pay actually regularly work more than 40 hours per week.

Unfortunately, the impact of expanding overtime pay coverage is not as simple as giving 4.2 million workers’ a 50 percent raise for their overtime hours. In particular, the DOL recognizes that the cost of expanding overtime pay will result in lower base wages and fewer weekly hours for roughly 1.5 million workers who either occasionally work overtime or regularly work overtime.

To evaluate the proposed overtime rule’s impact on wages and hours, the DOL breaks the 4.2 million newly covered workers into four main types, which are shown in Table 2.

|

Table 2: The DOL’s Worker Types |

||

| Category |

Number |

Percent |

| Total |

4,163,000 |

100.0% |

| Type 1 |

2,523,000 |

60.6% |

| Type 2 |

815,000 |

19.6% |

| Type 3 |

730,000 |

17.5% |

| Type 4 |

95,000 |

2.3% |

Type 1 workers never work overtime and will thus not be impacted by this rule change. DOL estimates that there are 2.5 million Type 1 workers, representing 60.6 percent of all newly covered workers. Type 2 workers are those who only occasionally work overtime and would be somewhat impacted by the rule. DOL estimates that 815,000 workers fall under this category. Type 3 worker workers are the 730,000 workers who regularly work overtime and will see the largest declines in wages and weekly hours. Finally, Type 4 workers also regularly work overtime, but earn a salary high enough that DOL expects their employers to increase their pay so they remain exempt. As a result, their wages will increase and their hours will not change. Only 95,000 workers fall under this category.

Table 3 illustrates how DOL expects the new overtime pay rule to impact these workers’ wages and hours.

|

Table 3: Overtime Rule’s Impact on Wages and Hours |

||

| Category |

Wages |

Hours |

| Total |

-0.8% |

-0.2% |

| Type 1 |

0.0% |

0.0% |

| Type 2 |

-0.4% |

-0.1% |

| Type 3 |

-5.3% |

-0.8% |

| Type 4 |

1.3% |

0.0% |

DOL estimates that on average, wages and hours for all 4.2 million workers will decline by 0.8 percent and 0.2 percent, respectively. However, since the wage and hour effects will be concentrated on those who regularly work overtime, these figures hide the negative pay consequences for some workers. In particular, DOL estimates that regular wages and hours for Type 3 workers (those who regularly work overtime) will fall by 5.3 percent. In addition, their hours will fall by 0.8 percent. Meanwhile wages for Type 4 workers (those who’s weekly pay will rise so they remain exempt) will increase 1.3 percent and their hours will not change.

After taking into account the changes in hours and wages, DOL finds that the actual net benefit from earning overtime pay would be very small. The average per worker net weekly income change is shown in Table 4.

|

Table 4: Overtime Rule’s Net Impact on Weekly Pay |

||

| Category |

Change in Weekly Pay |

Percent |

| Total |

$5.48 |

0.7% |

| Type 1 |

$0.00 |

0.0% |

| Type 2 |

$8.63 |

1.1% |

| Type 3 |

$19.97 |

2.8% |

| Type 4 |

$12.70 |

1.4% |

According to DOL, across all 4.2 million newly covered workers, the average weekly pay increase only comes out to be $5.48. While average weekly earnings will not change for Type 1 workers, they will only increase by $8.63 for Type 2 workers, $19.97 for Type 3 workers, and $12.70 for Type 4 workers. DOL estimates that on net, the standard salary level increase will raise pay by $1.2 billion per year. That’s only 0.3 percent of the $344.3 billion that total wage earnings in the United States grew between 2013 and 2014.[2]

Businesses Face Major Costs

While this rule’s actual benefits for workers will be minimal, businesses would face significant compliance costs and paperwork burdens.

Breakdown of Compliance Costs

- Total Costs (over 10 years): $2 billion

- Annualized Costs: $265.8 million

- Paperwork Burden: 231,250 hours

Final Rule:

- Total Costs (over 10 years): $2.9 billion

- Annualized Costs: $304.3 million

- Paperwork Burden: 2,507,338 hours

Regulatory Analysis

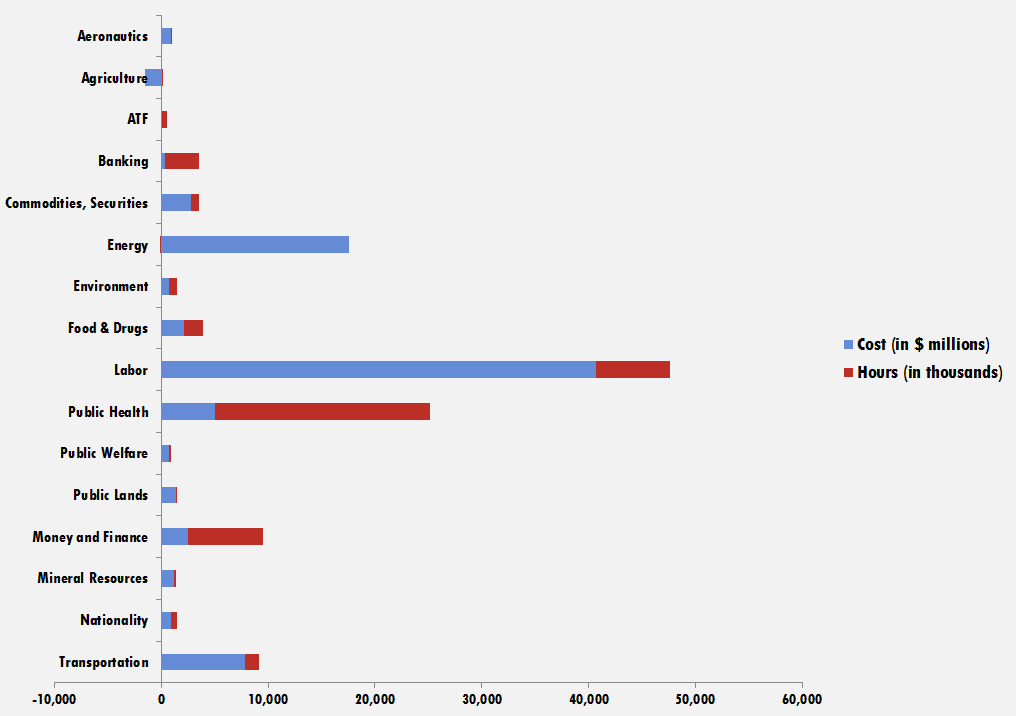

DOL estimates that total costs and paperwork will substantially increase from the rule’s proposed version. At nearly $3 billion in total costs, this rule is now the 4th most expensive DOL rule since 2006 (or third place if you disregard the nullified-yet-reissued 2010 Fiduciary rule). Adding it to DOL’s 2016 tally means that rules from the agency this year make up more than 80 percent of the its total costs since 2006. The graph below illustrates the pace of labor’s regulatory burdens relative to other issue areas so far in 2016:

Although the overall price tag is significant, the paperwork increase is even more dramatic. The final paperwork burden estimate is more than ten times that of its proposed version. Why is this? According to DOL: “This Final Rule does not impose new information collection requirements; rather, burdens under existing requirements are expected to increase as more employees receive minimum wage and overtime protections due to the proposed increase in the salary level requirement.” The agency re-iterates this further, stating: “The actual recordkeeping requirements are not changing in the Final Rule. However, the pool of workers for whom an employer will be required to make and maintain records has increased under the Final Rule, and as a result the burden hours have increased.” Yet, a deeper look into their figures demonstrates how much this information collection will actually affect these additional respondents.

According to DOL, the two information collection requirements (ICR) under the rule (ICR # 1235-0018 and 1235-0021) will undergo the following increases:

- 2,508,683 Respondents

- 2,554,673 Responses

- 2,507,338 Hours

This means that each new response will involve just under one hour (58.9 minutes). However, look at the respondents already subject to these requirements according to DOL:

- 3,040,664 Respondents

- 43,540,549 Responses

- 994,703 Hours

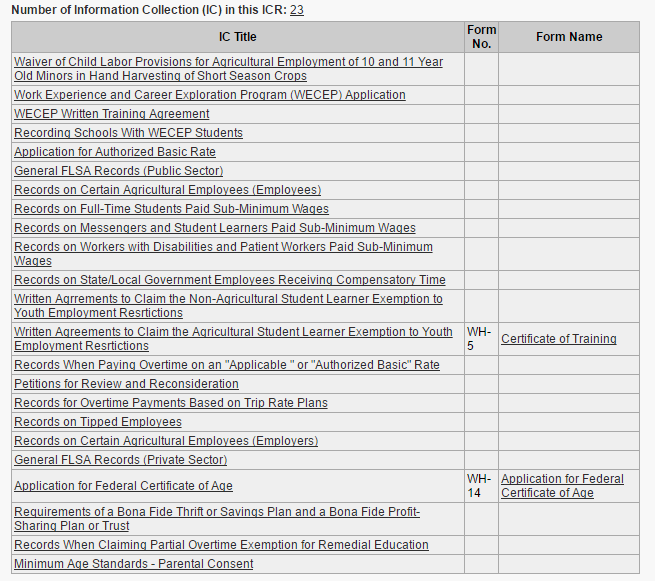

That yields roughly a mere 1.4 minute per response rate. Thus, for these newly covered entities, the regulatory familiarization and readjustment learning curve means taking an hour to do what currently takes roughly 80 seconds per response. Even the current rate seems somewhat incredulous considering it involves 23 information collections:

Conclusion

The DOL’s new overtime rule is being celebrated as a way to increase incomes for hardworking low- and middle-income families. A careful reading of the rule itself, however, reveals it will do very little for workers. The DOL projects that only about 825,000 workers will actually regularly benefit with an increase in weekly pay and that those workers would only receive at most an extra $20 per week. This is not something most rational people would call a “major victory for working people.” Meanwhile, the rule will impose billions in compliance costs and burden the economy with millions of fewer hours of work.

[1] 29 CFR Part 541, RIN 1235-AA11, “Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees, Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor, May 2016, Final Rule, https://s3.amazonaws.com/public-inspection.federalregister.gov/2016-11754.pdf

[2] Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages, Bureau of Labor Statistics, http://www.bls.gov/data/