The Daily Dish

September 9, 2021

Medicare and the Map

Eakinomics: Medicare and the Map

Medicare is an entitlement program, and the traditional Medicare program guarantees access to health services by seniors. But, in the end, providing those services is a business. And as it turns out, the cost of doing business varies considerably across the country. As Jackson Hammond puts it in his new research Primer: Geographic Adjustment of Medicare Rates, “The cost of providing the treatment is itself influenced by multiple variables: the amount of labor and the mix of labor used in providing the treatment (potentially involving physicians, nurse practitioners, orderlies, or other providers); and the capital costs of the provider, including rent and taxes. Cost of living directly impacts the price of labor, so personnel costs vary substantially based on location. Similarly, rent and taxes vary substantially between different communities.”

So, in order to provide the same therapies and treatments to all beneficiaries, Medicare must adjust the reimbursement amounts to compensate for these differences in the cost of providing services. As explained in much detail by Hammond, there are two main geographical adjustments: (1) the Hospital Wage Index (HWI) and (2) the Geographic Practice Cost Index (GPCI). The former is intended to directly address differences in the wages of medical personnel in Medicare Part A, while the latter is designed to capture a broader array of costs of doing medical business in Medicare Part B.

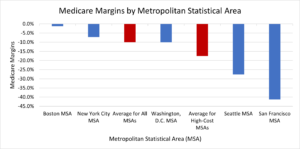

So, no problem, right? Not quite. Consider the graph (below) reproduced from Hammond’s primer. It shows the Medicare margins (the percent of costs that Medicare payments cover) for short-term care hospitals in high-cost areas versus the national average. As the data show, Medicare on average does not fully cover costs, but does a much poorer job in high-cost areas such as Seattle (-27.7 percent) and San Francisco (-41.2 percent).

So, what is the problem? Hammond identifies a slew of problems ranging from the fact that only nursing salaries are used for wage data (hospitals need plumbers and carpenters and many others), to the fact that the data are not updated frequently, to the complexity of the adjustment formulae, to the fact that any increased reimbursement in one part of the country must be offset (“budget neutrality”) elsewhere. And the list goes on. The mechanics of geographic adjustment are simply not up to meeting the conceptual standard.

Stepping back, the real problem is central planning (footnote: see Soviet Union, defunct). There is no way for Medicare officials to genuinely measure the quality of care, so there is no way to measure quality-adjusted unit costs, so there is no way to reimburse those costs. And no federal official can know the on-the-ground mix of inputs that each provider uses across the country. And even if it started out right, no federal bureaucracy is nimble enough to stay independent of politics and on top of new developments.

Central planning does not have the information or incentives to get it right. Since the Biden Administration and Congress are dead set on dragging the federal central planners into new lines of business in child care, pre-K, community college, and others, we can anticipate more delivery system problems in the years to come.

Fact of the Day

Ending the $300 a week unemployment supplement in nearly half of U.S. states was correlated with a 14 percent reduction in initial claims.