The Daily Dish

January 12, 2023

The FTC Meets Noncompetes

On January 5, Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chair Lina M. Khan issued a clarion call to unchain the American worker: “The freedom to change jobs is core to economic liberty and to a competitive, thriving economy.” The problem? Noncompete Agreements (NCAs): “Noncompetes block workers from freely switching jobs, depriving them of higher wages and better working conditions, and depriving businesses of a talent pool that they need to build and expand. By ending this practice, the FTC’s proposed rule would promote greater dynamism, innovation, and healthy competition.”

Liberty! Innovation! Dynamism! Competition! Puppies! Kittens! Sunshine! Eakinomics was pumped. What was going on?

As it turns out: “The Federal Trade Commission proposed a new rule that would ban employers from imposing noncompetes on their workers, a widespread and often exploitative practice that suppresses wages, hampers innovation, and blocks entrepreneurs from starting new businesses. By stopping this practice, the agency estimates that the new proposed rule could increase wages by nearly $300 billion per year and expand career opportunities for about 30 million Americans. The FTC is seeking public comment on the proposed rule, which is based on a preliminary finding that noncompetes constitute an unfair method of competition and therefore violate Section 5 of the Federal Trade Commission Act.”

NCAs are contracts between employer and employee signed at the onset of employment that prohibit the employee from competing with their former employer upon separation – particularly for a specific geography and over a specific amount of time.

“Exploitive,” “hampers innovation,” and “blocks entrepreneurs” does sound bad, but are NCAs really a big deal? After all, that massive $300 billion in wages would mean just a 2 percent increase in employee compensation. The Biden Administration routinely wipes out many multiples of that in consumer price inflation. Moreover, one would expect that a worker would not knowingly enter into an NCA – forfeiting future options – without a compensating increase in current pay. And previous AAF research had indicated that NCAs made sense in certain C-suite executives and employees with knowledge of trade secrets, and concern only arose when NCAs “trickled down the organizational chart to include even entry-level employees.” There is the further empirical question of whether entry-level NCAs are really enforced: Has Subway ever really gone after a former employee across the street at Jimmy John’s?

Bottom line, does a blanket prohibition on NCAs pass a benefit-cost test? Eakinomics has its doubts.

The second issue is whether the FTC has the authority to do this. As Fred Ashton points out in his review of the FTC proposed rule, the agency is just following orders. “President Biden’s executive orderon Promoting Competition in the American Economy included a directive for the Chair of the FTC to use the agency’s rulemaking authority to ‘curtail the unfair use of non-compete clauses…that may unfairly limit worker mobility.’” This order set in motion a series of events that culminated in the proposed rule.

But even if the president wants the FTC to undertake this rulemaking, there are reasons to doubt that Congress has given the FTC the authority to do so. Indeed, the legislation creating the FTC has been repeatedly revised over the years specifically because the agency is a serial over-stepper of its rulemaking authorities. And layered on top of this is the “major questions doctrine” invoked in the recent Supreme Court ruling in West Virginia v. EPA. The desirability of a nationwide intervention in all new labor contracts and an ex post revision of all existing contracts with NCAs does seem like a major question that only Congress could settle. It is simply above the FTC’s pay grade.

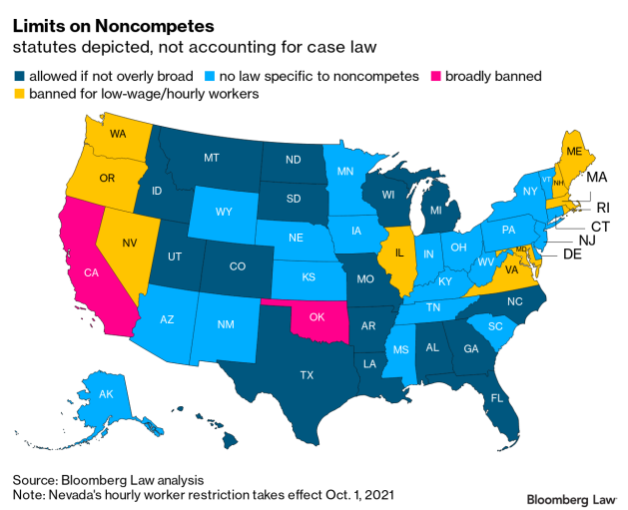

Finally, even if it has the authority, does this pass the Mama Eakin test? After all, just because you can do something, it does not mean that you should do something. Banning NCAs is a classic one-size-fits-all, liberal strategy. In contrast, labor markets differ dramatically across the United States. As it turns out, the states have been quite active in differing approaches to NCAs:

If the states are keeping an eye on the best interests of labor market competition in their borders, why should the FTC override their efforts?

In the end, the proposed rule is less a clarion call on behalf of the American worker than a self-serving exercise by an overreaching federal bureaucracy.

Fact of the Day

Based on 2021 data, Section 301 tariffs on imports from China covered over $260 billion worth of goods and cost U.S. consumers $48 billion.