Insight

February 23, 2017

Reconsidering Investing Social Security in Equities

The last time the U.S. considered a fundamental Social Security reform, the proposal stalled on Capitol Hill, and subsequent political candidates have shied from any further reform efforts. The concept of personal retirement accounts was a casualty of this process. The subsequent recession appeared to validate many critics’ concerns that exposing Social Security to stock market risk would jeopardize the social safety net. Despite the troubled politics and the 2008 recession however, the concept remains sound and should be considered in the future. Indeed, even including the great recession, retirees would be better off if some portion of their retirement were invested in equities rather than under the current system.

Social Security provides retirement benefits based on past work history. The system is financed with payroll taxes by current workers and borrowing from the public to provide cash benefits to retirees. The Social Security system is invested in non-marketable Treasury securities that account for past contributions and receive a rate of return based on a basket of U.S. Treasuries.[1] While the interest rate earned by the Social Security system is not entirely analogous to a return on investment, it does provide a useful benchmark for comparison to returns on equities and other securities. According to researchers from Boston College’s Center for Retirement Research, the geometric mean return on the S&P 500 stock index between 1928 and 2015 was 9.5 percent, while returns on Treasuries were far lower, 3.5 percent, and 5.0 percent on the 3-month and 10-year Treasuries, respectively.[2] This difference accrues dramatically over time: $100 invested in the S&P 500 in 1928 would be worth than $294,000 at the end of 2015. $100 steadily reinvested in the 10-year Treasury over the same period would be worth $7,062 at the end of 2015.[3]

A retroactive look at how the Social Security system would have fared as a whole had it been invested in equities proves that retirees are leaving a lot of money on the table by being forced into the current system. Indeed, if the Social Security System had been invested in equities in 1984, the Social Security Trust Fund would have held $3.8 trillion in assets as of 2015, compared to actual holding of $2.8 trillion. If the equity investment had begun later, in 1997, the Trust Fund would have forgone some years of higher income growth, but would still have held $600 billion more assets than occurred under the current system.[4]

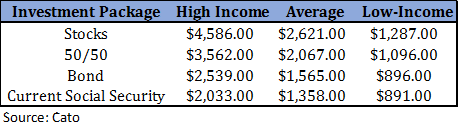

Importantly, this construct only illustrates the degree to which higher rates of return associated with equity investment compounding over time can benefit the system as a whole, and would merely have strengthened the system’s finances, forestalling future reductions in benefits when the Trust Fund becomes insolvent. A system of private accounts would allow for individuals to see higher benefits because of the higher returns. A study by Cato examined how workers who retired in 2011, right after the 2008 financial crisis, would have fared with individual accounts if they had been in available for 40 years and under different investment scenarios.[5] Under each scenario, the hypothetical workers are never worse off with the system of individual accounts and could have actually seen substantially increased benefits.

Hypothetical Workers Retiring in 2011

While the study has important caveats (these numbers, for instance can vary considerably between women and men and due to other factors), it does convey the attractiveness of allowing at least younger workers the ability to leverage the higher rates of return associated with investing in equities.

[1] https://www.ssa.gov/oact/progdata/intrateformula.html

[2] http://crr.bc.edu/wp-content/uploads/2016/07/wp_2016-6.pdf

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] https://object.cato.org/sites/cato.org/files/pubs/pdf/PA692.pdf