Testimony

June 15, 2016

The Need for Budget Process Reforms

Introduction

Chairman Price, Ranking Member Van Hollen and members of the Committee, I am pleased to have the opportunity to appear today and speak to the need for reforming the federal budget process. In this testimony, I wish to make a few basic points:

- The current budget process itself is flawed, disjointed, and does not actually produce anything that should be called a “budget,”

- The result of the current process has been a series of adverse outcomes such as government shutdowns and most federal expenditures operating on autopilot,

- To address these failures, I would recommend material reforms to the Congressional Budget Act that reorient the budget process to a fiscal goal, and

- Lastly, I would caution that budget process reforms – however commendable – should be pursued, but are no substitute for necessary underlying policy changes.

Let me discuss each in turn.

The Modern Budget Process

The current process for establishing the federal budget was borne of dysfunction. Prior to the enactment of the Congressional Budget and Impoundment Act of 1974, Congress created the Joint Study Committee on Budget Control to address perceived failures in the existing budget process that gave rise to “growing deficits, excessive spending and a growing portion of outlays considered to be ‘relatively uncontrollable’ and an undue reliance upon the executive for budgetary information and analysis.”[1] Of further concern to Congress was then-President Nixon’s impoundment of over 10 percent of appropriated funds that stretched the executive branch’s authority over the nation’s fiscal matters.[2] To address these challenges, and clarify the exercise of its “power of the purse,” Congress passed the Budget Act, which established the budget process that we bemoan today.

The Budget Act reasserted the role of Congress in the federal budget process, and in establishing the Budget Committees and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) created important institutions that have served the nation well. Despite these contributions, the challenges that the Act sought to address persist to this day. The budget process still does not produce a cohesive budget for any given fiscal year.

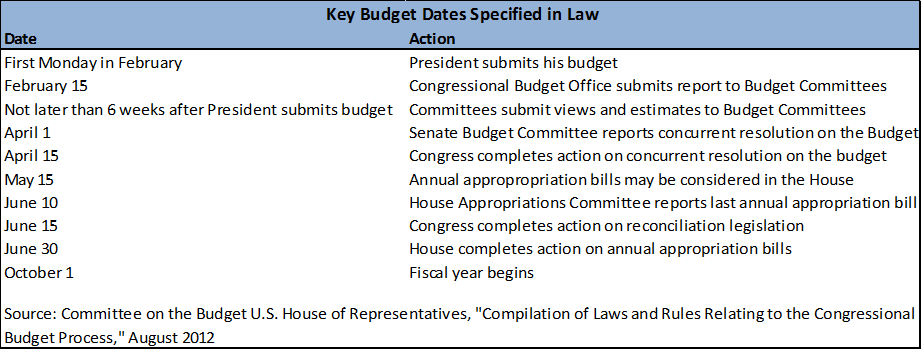

Section 300 of the Congressional Budget Act established what has proven to be an optimistic timetable for establishment of the budget for a fiscal year:

Table 1: Timetable for the Congressional Budget Process

A review of administration and congressional adherence to this timetable reveals a history of missed deadlines and unfinished business. In terms of strict observance of these deadlines, both the executive branch and Congress routinely complete timely action on the budget. To begin, 6 of the past 8 budgets from the current administration have been late arriving.[3] This further compresses the budget timetable, and impedes prompt completion of the succeeding steps on budget matters. For its part, Congress has failed to complete action on a budget resolution in 6 of the past 10 years. Owing to these delays and inaction, Congress has competed work on time on all 12 of its appropriations bills just 4 times in the 40-year history of the Congressional Budget Act.[4] Clearly, the process is broken.

The Cost of a Broken Budget Process

Failure to adhere to the timetable set forth in the Congressional Budget Act would not necessarily warrant concern if the process eventually led to a stable and coherent fiscal policy. Unfortunately, the federal government does not have a fiscal “policy.” Instead, it has fiscal “outcomes.” As noted, the House and Senate do not reliably agree on a budget resolution, and when they do, the executive branch does not necessarily concur, having only been meaningfully engaged at the end of the appropriations process. While this end-of-year engagement is often uneventful, discord can prove costly and dramatic in the form of a government shutdown.[5] While process alone cannot bridge fundamental political divides, the bifurcated process currently in place hardly engenders collaboration between the executive and legislative branches.

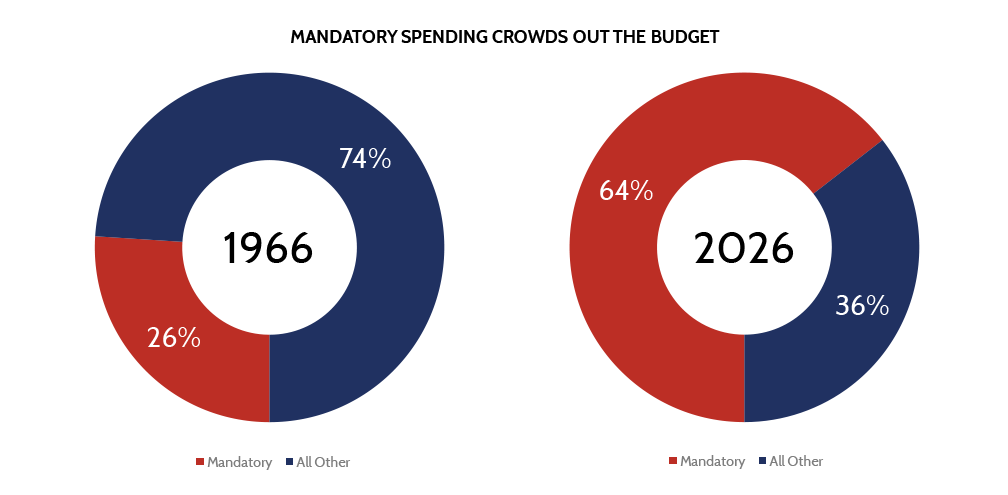

While breakdowns in the budget process are costly and foster public distrust of the federal government, they reflect debates over only about one third of federal expenditures – discretionary spending.

Figure 1: Federal Expenditures Increasingly on Autopilot

The budget “process” governs an ever-smaller share of federal expenditures. Indeed, as dramatic as disruptive as government shutdowns appear, they reflect discrepancies over a relative pittance in the context of total spending. According to the most recent CBO projections, the composition of federal spending will essentially flip from being dominated by discretionary spending subject to annual appropriation to a two-thirds composition of entitlement spending, which is effectively walled off from the annual budget process.

Annual discretionary spending is not coordinated in any way with the outlays from mandatory spending programs operating on autopilot. Nothing annually constrains overall spending to have any relationship to the fees and tax receipts flowing into the U.S. Treasury. And debt service costs merely reflect credit markets’ appetite for financing these gaps. The fiscal outcome is whatever it turns out to be – usually bad – and certainly not a policy choice.

The budget process is intended to facilitate a regular and disciplined evaluation of the inflow of taxpayer resources and outflow of federal spending. It should enhance the role of the Congress as a good steward of the federal credit rating. It does neither because the current process is insufficiently binding. As a result, it easily degenerates to the mere adoption of current-year discretionary spending levels, with no review of the real problem: the long-term commitments in mandatory spending and increased borrowing costs.

These core, long-term issues have been outlined in successive versions of the CBO’s Long-Term Budget Outlook.[6] In broad terms, the inexorable dynamics of current law will raise federal outlays from an historic norm of about 20 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to anywhere from 30 to nearly 40 percent of GDP. Spending at this level will far outstrip revenue, even with receipts projected to exceed historic norms, and generate an unmanageable federal debt spiral.

This depiction of the federal budgetary future and its diagnosis and prescription has all remained unchanged for at least a decade. Despite this, meaningful action (in the right direction) has yet to be seen, as the most recent budgetary projections demonstrate.

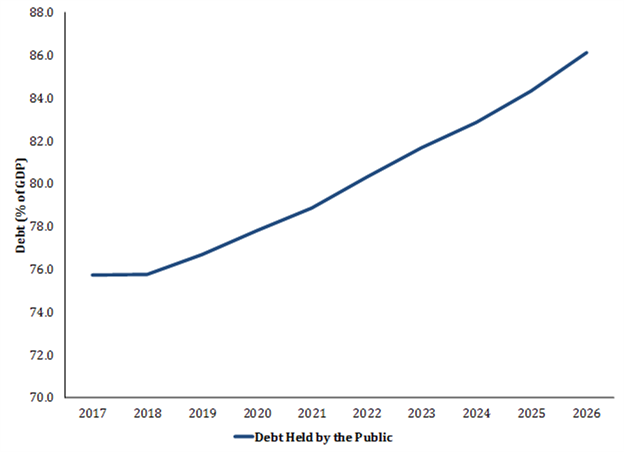

The basic picture from CBO’s most recent budget projections is as follows: tax revenues return to pre-recession norms, while spending progressively grows over and above currently elevated numbers. The net effect is an upward debt trajectory on top of an already large debt portfolio. The CBO succinctly articulates the risk this poses: “Such high and rising debt would have serious negative consequences for the budget and the nation… Such high and rising debt relative to the size of the economy would dampen economic growth and thus reduce people’s incomes compared with what otherwise would be the case. It would also increasingly restrict policymakers’ ability to use tax and spending policies to respond to unexpected challenges, and it would boost the risk of a fiscal crisis in which the government would lose its ability to borrow at affordable rates.”[7]

Figure 2: Debt Ultimately on an Upward Trajectory

The trajectory, direction and the magnitude of the federal debt outstanding is ultimately the most telling characteristic of the U.S. fiscal path. The widely acknowledged drivers of the long-term debt – health and retirement programs for aging populations, and borrowing costs – will begin to overtake higher than average tax revenue and steady economic growth by the middle of the decade, and grow ever inexorably upwards until creditors effectively refuse to continue to finance our deficits by charging ever higher interest payments on an increasingly large debt portfolio. This crisis state is more pernicious than mere stabilization of the debt at a high level, which would suppress economic growth as financing the debt crowds out other productive investment. Rather, unchecked accumulation of debt would precipitate a fiscal crisis that would upend world financial markets and do lasting harm to the nation’s standard of living.

The current budget process does not meaningfully address this fundamental challenge. Any reforms to the budget process should recognize this deficiency and facilitate the achievement of budget goals and targets that would improve the nation’s fiscal trajectory.

Suggestions for Reform

The most striking failure of the federal budget process is that it is not a process at all, or at least not a process oriented towards a goal. The Committee should consider reforming the Budget Act to incorporate a specific budget goal. Section 301 of the Budget Act sets forth the content of the budget resolution and includes a number of budget metrics. 301(b)(4) allows for “such other matters, and require such other procedures, relating to the budget, as may be appropriate to carry out the purposes of this Act,” and could accommodate the stipulation of a specific goal in a budget resolution.

Reforming the Budget Act to reflect the need to produce a specific goal would be a healthy public policy debate in and of itself. This reform should not include a specific budget goal in the Budget Act itself, but rather dictate the content of budget resolutions. This goal should then inform the other totals, aggregates, and assumptions that form the content of the budget resolution and ultimately congressional consideration.

A firm understanding of the nation’s existing fiscal position is essential to achieving a given budget goal. The Budget Act sets forth the current process for constructing the budget baseline, essentially the lodestar for fiscal policy. Only since January of this year has CBO’s “current law” baseline closely resembled current policy.”[8] For the past decade, the disparate treatment of tax and spending policies in the baseline created a multi-trillion dollar gap between what the nation’s budget path was under “current law” and what it would likely be based on what Congress and the executive branch routinely adopted as policy. The largest driver of this gap was the scheduled “sunset” of tax policies enacted in the early 2000s, which like all tax policies are affixed with expiration dates in the baseline unless routinely extended. Contrasted with major spending programs, which grow with projections of costs and beneficiaries in the case of entitlements or the last year’s appropriations plus inflation in the case of discretionary spending, tax policy faces an unrealistic bias in the baseline. The annual tax “extenders” exercise was a reflection of this treatment. While Congress addressed many of these gaps through legislation, formal adoption of current policy as the baseline would provide greater clarity to lawmakers and assist in the achievement of budget goals.

While I have painted an admittedly bleak picture of the federal budget process, there is also recent cause for optimism. First, this hearing and similar efforts in the Senate reflect a recognition of the need for improvement. I believe there is sincere interest by both parties to improve the process. Second, the Congress has already adopted one important budget reform: dynamic scoring. I have long advocated for incorporating macroeconomic estimates in the scorekeeping process where appropriate.[9] Requiring dynamic scores for economically significant policy changes strengthens the budget process and assists policy makers in sorting policy options that might appear equal in budget terms on a static basis, but have very different economic effects, which in turn affect the budget.

Necessary Political Will

Process reform, no matter how well intentioned or considered is no substitute for the actual reforms needed to address the looming debt crisis fueled by federal spending. No reform to the Budget Act or statutory spending cap or sequester can replace the needed debate on what should be a realistic or fair retirement age, or what is the proper federal role in seniors’ health care delivery. So while I commend any meaningful improvement to process reform, I would also caution this Committee’s membership that the clock is ticking on the need for that broader discussion.

Thank you. I look forward to your questions.

*The opinions expressed herein are mine alone and do not represent the position of the American Action Forum. I thank Gordon Gray for his assistance.

[1] http://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/BudgetCommitteeHistory2.pdf

[2] Ibid.

[3] https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/browse/collectionGPO.action?collectionCode=BUDGET

[4] http://www.budget.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/FINAL.Process%20Reform%20BB042816%202.pdf

[5] http://www.americanactionforum.org/research/government-shutdowns-what-they-are-and-what-they-are-not/

[6] Congressional Budget Office. 2015. The Long-Term Budget Outlook. Pub. No. 50250. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/50250

[7] Congressional Budget Office. 2016. The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2016 to 2026. Pub. No. 51129. https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/51129-2016Outlook.pdf

[8] http://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/cbos-january-baseline-closer-to-reality/

[9] http://waysandmeans.house.gov/UploadedFiles/Holtz-Eakin_Testimony_SRM_073014.pdf