Testimony

April 11, 2018

Unleashing America’s Economic Potential: Testimony to the Joint Economic Committee

Introduction

Chairman Paulsen, Ranking Member Heinrich and members of the Committee: I am honored to have the opportunity to testify on the necessity of a pro-growth policy agenda. Pro-growth policies are essential for ensuring that current and future American families enjoy the same—or greater—improvements in their living standards as previous generations.

In my testimony, I wish to make three simple points:

- Encouraging more rapid long run economic growth remains the most pressing policy issue faced by the Congress;

- The Trump Administration has pursued a policy agenda that has had a mixed effect on the economic outlook – with tax reform and regulatory policy achievements contributing positively to the growth outlook, but immigration and trade policies introducing needless economic headwinds; and

- Notwithstanding the policy developments of the past year, considerable work remains to improve the economic trajectory of the United States.

Let me discuss these in turn.

Recent Economic Performance and the Growth Challenge

Supporting more rapid trend economic growth is the preeminent policy challenge. The nation has experienced a disappointing recovery from the most recent recession and confronts a projected future defined by weak economic growth. Left unaddressed, this trajectory will give the next generation a less secure and less prosperous nation.

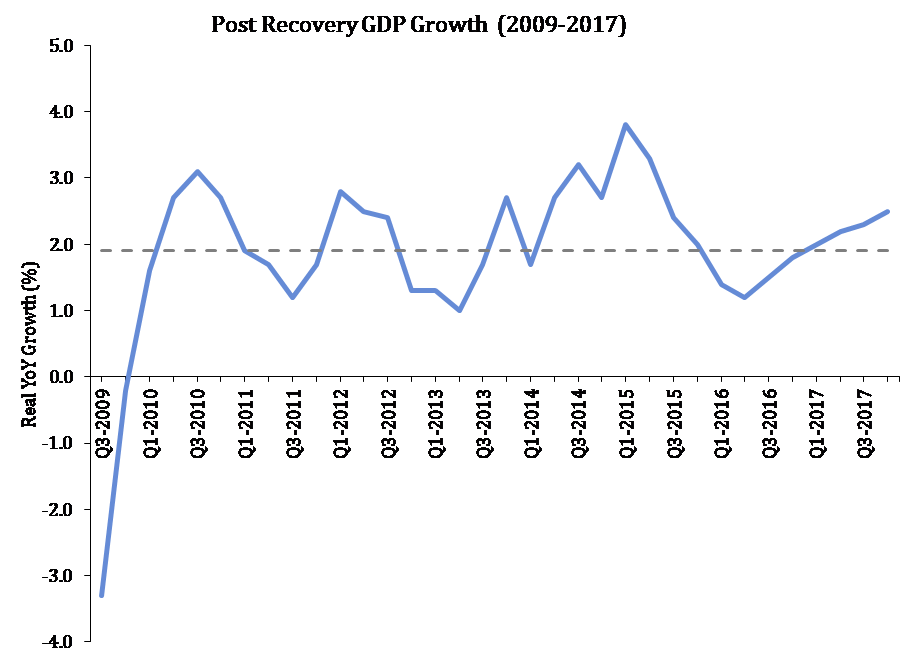

Figure 1: Disappointing Economic Growth

Figure 1 shows quarterly, year-over-year growth rates for real gross domestic product (GDP) since the official end of the Great Recession in June of 2009. As displayed, real GDP growth has been stubbornly weak, averaging 1.9 percent (the dotted line). While recoveries from recessions precipitated by financial crises tend to be weaker, the persistence of the nation’s weak economy should not be considered inevitable, but rather as an encouragement to implement better economic policy.

Figure 2: Productivity Growth is Lagging Past Performance

Household income, a metric that more working Americans can appreciate, underscores the tepid economic recovery. According to the most recent comprehensive income survey conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau, earnings growth of men and women who worked full-time and year-round was essentially zero in 2016.[1] Stagnant earnings growth reflects poor productivity growth that lags behind the rate seen in other recoveries or the prevailing historical trends (see Figure 2).[2]

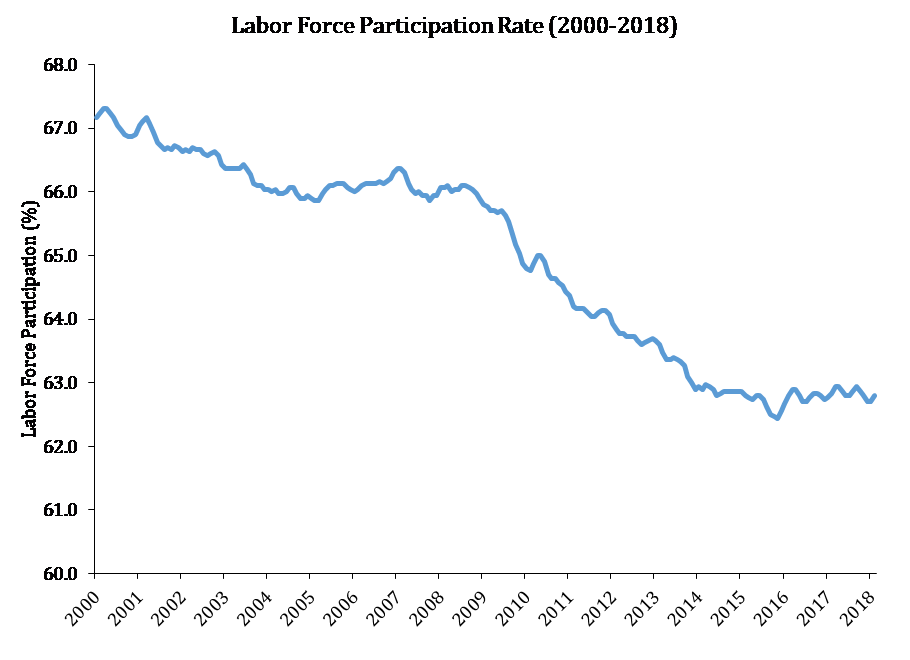

Figure 3: Labor Force Participation

The other essential building block for stronger trend economic growth is growth in the labor force – the population willing and able to work. As a share of the population, the labor force has declined from historical highs in 2000, but this decline has accelerated since the Great Recession (Figure 3).

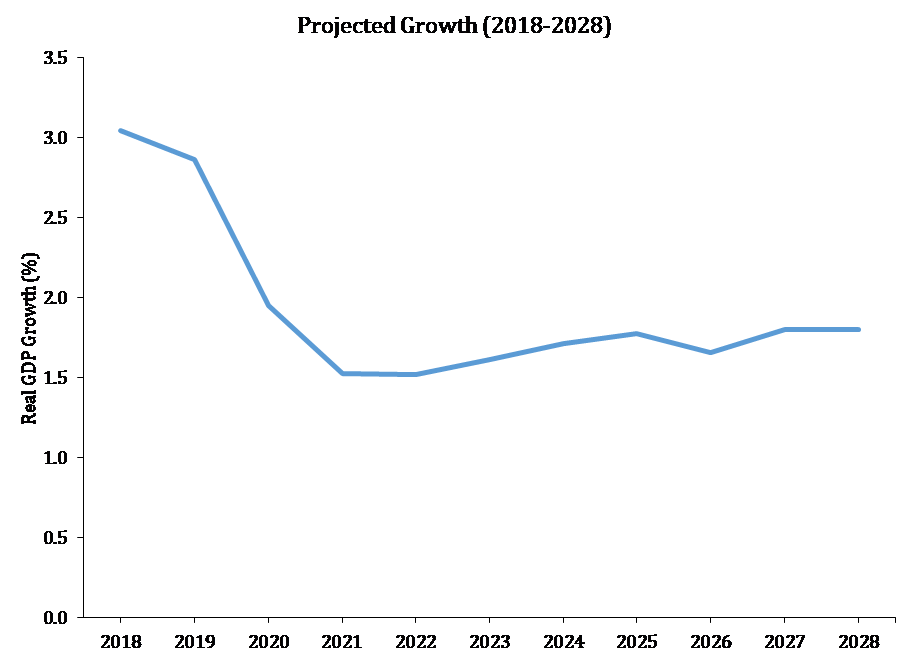

Figure 4: CBO April 2018 Baseline

Even more troubling than the recent economic past is the outlook. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected in its April Budget and Economic Outlook that U.S. economic growth will average 1.9 percent over the period 2018-2028. This is essentially unchanged on average from CBO’s June projections, but reflects near-term improvement largely attributable to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) that dissipate over the budget window.

The rate of growth projected in the current economic baseline is certainly below that needed to improve the standard of living at the pace typically enjoyed in post-war America. During the early postwar period, from 1947 to 1969, trend economic growth rates were quite rapid. GDP and GDP per capita grew at rates of 4.0 percent and 2.4 percent, respectively. Over the subsequent 25 years, however, these rates fell to 2.9 percent and 1.9 percent, respectively. During the years 1986 to 2007, trend growth in GDP recovered to 3.2 percent, while trend GDP per capita growth rose to 2.0 percent.

These rates were quite close to the overall historic performance for the period. These distinct periods and trends should convey that the trend growth rate is far from a fixed, immutable economic law that dictates the pace of expansion, but rather is subject to outside influences – including public policy.

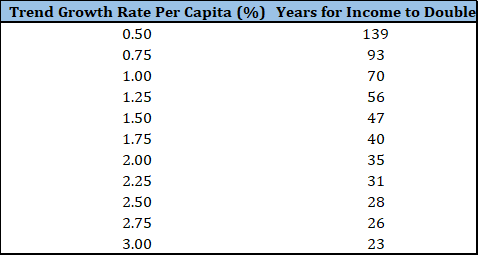

Table 1: The Importance of Trend Growth to Advancing the Standard of Living

The trend growth rate of postwar GDP per capita (a rough measure of the standard of living) has been about 2.1 percent. As Table 1 indicates, at this pace of expansion an individual could expect the standard of living to double in 30 to 35 years. Put differently, during the course of one’s working career, the overall ability to support a family and pursue retirement would become twice as large.

In contrast, the long-term growth rate of GDP in the most recent CBO projection is 1.9 percent. When combined with population growth of 0.8 percent, this implies the trend growth in GDP per capita will average about 1.0 percent. At that pace of expansion, it will take 70 years to double income per person. The American Dream is disappearing over the horizon.

More rapid growth is not an abstract goal; faster growth is essential to the well-being of American families.

A Policy Regime for Faster Trend Growth – Assessing Recent Developments

Given the poor growth legacy of the last administration, Congress and the current administration must break from the economic policies of the past decade.. “Economic growth policy” is more a philosophy than a piece of legislation. It is a commitment at every juncture in the policy process to evaluate tradeoffs between social goals, environmental goals, special interest goals, and economic growth – and then to err on the side of growth.

The second flaw in the prior administration’s policy approach was its misguided reliance on temporary, targeted piecemeal policymaking. Even if one believed that countercyclical fiscal policy (“stimulus”) could be executed precisely and had multiplier effects, it is time to learn from experience that this strategy is not working. The various stimulus programs – the Economic Stimulus Act of 2008(checks to households), the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (the gargantuan stimulus bill in 2009), the Car Allowance Rebate System (“cash for clunkers”), the Federal Housing Tax Credit (tax credits for homebuyers), the HIRE Act (consisting of a $13 billion payroll hiring credit, expensing of certain investments, $4.6 billion for schools and energy), the Small Business Jobs Act of 2010, and the state-local bailout Public Law 111-226 ($10 billion to education; $16 billion to Medicaid) – all have failed to generate adequate growth.

Just as the policy regime of macroeconomic fiscal (and monetary) fine-tuning backfired in the 1960s and 1970s, leaving behind high inflation and chronically elevated unemployment, this regime has worked no better in the 21st century. The Trump Administration and the Congress have an opportunity to commit to raising the long-term growth rate of the economy through permanent reforms. We have seen some noteworthy progress toward this goal, specifically with respect to tax reform and regulatory policy. But the administration has also pursued trade and immigration policies that are decidedly anti-growth, risking the progress made in other areas of economic policy. This Committee can and should continue to serve as a forum for encouraging sound economic policies that support a pro-growth agenda and dissuading those policies that impede such an agenda.

Tax Reform

Prior to the enactment of the TCJA, the U.S. tax code was broadly viewed as broken and in need of repair, and for good reason. Whereas the previous administration and past Congresses made the tax system worse – adding higher rates and new taxes, including on the middle class – the Trump Administration and Congress embarked on an effort to overhaul the fundamentals of the nation’s tax system. A sound reform of the U.S. tax code was an essential element of a pro-growth strategy, and this reform promises to support substantially increased long run economic growth.[3]

The last time the United States undertook a fundamental tax reform was with the Tax Reform Act of 1986 (TRA). A robust literature demonstrates negative relationships between higher marginal rates and taxable income, hours worked, and overall economic growth.[4] Highly respected economists David Altig, Alan Auerbach, Laurence Kotlikoff, Kent A. Smetters, and Jan Walliser simulated multiple tax reforms and found GDP could increase by as much as 9.4 percent because of tax reform.[5] The highest growth rate was associated with a consumption-based tax system that avoided double-taxing the return to saving and investment. The study also simulated a “clean,” revenue-neutral income tax that would eliminate all deductions, loopholes, etc., and lower the rate to a single low rate. According to their study, this reform raised GDP by 4.4 percent over 10 years – a growth effect that roughly translates into about 0.4 percent higher trend growth, resulting in faster employment and income growth. This theoretical work essentially staked out the upper bound for the growth potential from tax reform.

The TCJA addressed some of the most glaring flaws in the business tax code:It lowered the corporation income tax rate to a more globally competitive 21 percent, enhanced incentives to investment in equipment, addressed some of the disparate tax treatment between debt and equity, and refashioned the nation’s international tax regime. Primarily for these reasons, the TCJA will enhance the nation’s growth prospects. The likely growth effects over the long-term will fall short of the theoretical ideal but will ultimately be positive. The long-run contribution to GDP from the TCJA could be as much as 3 percent, though there are a range of credible estimates and myriad factors that could alter the ultimate impact of the TCJA on the economy.[6]

The TCJA is not an ideal tax reform, however, and there remains considerable opportunity for improving the law itself and the overall tax environment in the United States

Regulatory Reform

Perhaps the most striking policy departure from the previous administration has been in the area of regulatory reform. The Obama Administration finalized a costly regulation at the average rate of 1.1 per day, and the cost of complying with those regulations cumulated to $890 billion – according to the agencies themselves that issued the regulations. That cost is an average stealth tax increase of over $110 billion a year. Enter the Trump Administration, which from the president’s inauguration to September 30 of last year (the end of the federal government’s fiscal year) incurred essentially zero additional regulatory costs.[7] While much of the reduced regulatory burden identified by the administration can ultimately be traced to delays or paperwork reductions, the taming of the regulatory state has been remarkable. Congress also contributed to this effort by invoking the Congressional Review Act (CRA) to repeal 14 rules.[8]

Going forward, the Trump Administration has promised to make even more progress in reducing the burden of the regulatory state. For 2018, the administration produced a regulatory “budget” — the amount by which the nation’s 24 regulatory entities’ regulations are permitted to increase the overall cost of complying with regulations. These budgets, detailed by the American Action Forum’s (AAF) Dan Bosch, show that overall deregulation will accelerate. Annualized costs are to decline by $687 million, or an up-front $9.8 billion.[9] Not all entities must deregulate equally. eight got budgets of zero – that is, flat overall regulatory burdens – while the remaining 16 got negative targets – that is, continued deregulation. Of note, nobody got an increase. Among the decreases, the largest is the Department of Interior, with $196 million in annualized reductions, or $2.8 billion in up-front costs.

The current administration should also be commended for enforcing a common method of measuring regulatory costs, especially by making sure that every regulatory entity uses comparable time periods over which to do the cost accounting. The infrastructure of regulatory budgets and cost accounting have taken a very large step forward and will likely continue to evolve in the years to come.

Trade Policy

Trade is an important driver of productivity and economic growth in the United States and globally. Trade creates jobs, increases GDP, and opens markets to American producers and consumers. The United States is the world’s largest participant in global trade – with over $2.3 trillion in exports of goods and services and imports of over $2.9 trillion – and has established trade agreements with 20 countries.[10] The United States is the largest exporter of services in the world.[11] Trade supports over 11 million jobs in the United States[12] and U.S. exports comprise nearly 13 percent of U.S. GDP.[13]

It is therefore regrettable that the Trump Administration has embraced protectionism at the expense of the opportunities that global trade provides. The administration walked away from the Trans-Pacific Partnership, which offered both economic and geo-strategic benefits. More recently and notably, the administration has decided to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum for dubious “national security” reasons. The national security rationale is undermined by the Department of Defense, which notes in a memo that the military’s requirements for steel and aluminum can be met by a fraction of current domestic production.[14] Ultimately, these tariffs are likely to have the same effects of similar past actions – they will harm consumers, antagonize strategic and economic allies, and ultimately fail in their stated policy objections.[15]

Immigration Reform

Immigration reform can raise both population and labor force growth, and thus can raise GDP growth. In addition, immigrants inject entrepreneurialism into the U.S. economy.[16] New entrepreneurial vigor embodied in new capital and consumer goods promises a higher standard of living. Without this policy effort, low U.S. birth rates will result in a decline in the population and overall economy. An economically based immigration reform would raise the pace of economic growth substantially, raise GDP per capita, and reduce the cumulative federal deficit. It is therefore disappointing that the current administration has continued to pursue an immigration policy agenda that forgoes these benefits and threatens to diminish the effects of other pro-growth economic policies.

The Trump Administration has advocated restricting legal immigration, which is a sufficiently misguided policy as to earn the rebuke of nearly 1,500 economists, covering the spectrum of political preferences and including six winners of the Nobel Prize in Economics.[17] Restricting legal immigration would harm entrepreneurialism, accelerate the aging of the United States’ demographics, and disqualify the U.S. economy as a home for the innovation and diversity of skills that immigrants bring. The current administration’s chosen course of action with respect to Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals (DACA) also introduces needless policy risk to the economy. AAF’s Jackie Varas estimates that “the average DACA worker contributes $109,000 to the economy each year. If all DACA recipients were removed, U.S. GDP would decrease by nearly $42 billion.”[18] Put differently, the DACA population is an economic asset, and failure to address its uncertain status either through legislation or administrative action could undercut economic performance.

Structural Reforms to Enhance Trend Growth

The Unfinished Work of Tax Reform

The TCJA was an important first step in improving the U.S. tax code but should not be viewed as the final word in U.S. tax reform. Several features of the bill will need to be revisited and improved. Specifically, the temporary provisions should be made permanent. These include business and individual provisions, and expensing of qualified equipment should top the list of provisions that should be made permanent.

Making these changes permanent, however, should be done in a revenue neutral way. According to the President’s Budget, just making the individual and estate tax provisions of the TCJA permanent would cost $541.6 billion over the next decade.[19] It would be fiscally imprudent to layer this additional deficit effect on top of existing budget challenges.

The Trump Administration and Congress, with the assistance of this Committee, should also continue the reform effort of tax reform and continue to flatten distortions in the tax code. The tax preference for debt over equity, for instance, persists in the tax code and should be revisited.

Entitlement Reform and a Sustainable Debt Trajectory

One of the biggest policy problems facing the United States is that spending rises above any reasonable metric of taxation for the indefinite future. A mini-industry is devoted to producing alternative numerical estimates of this mismatch, but the diagnosis of the basic problem is not complicated. The diagnosis leads as well to the prescription for action. Over the long-term, the budget problem is primarily a spending problem and correcting it requires reductions in the growth of the largest mandatory spending programs – namely, Social Security and federal health programs.

At present, Social Security is running a cash-flow deficit, increasing the overall shortfall. There are even larger deficits and future growth in outlays associated with Medicare, Medicaid, and the Affordable Care Act (ACA). These health programs share the demographic pressures that drive Social Security, but include the inexorable increase in health care spending per person in the United States.

For this reason, an immediate reform and improvement in the outlook for entitlement spending would send a valuable signal to credit markets and improve the economic outlook. The United States is courting a further credit downgrade as a sovereign borrower and the ensuing increase in borrowing costs such a downgrade would generate. Any sharp rise in interest rates would have dramatically negative economic impacts. Moreover, an actual liquidity panic would replicate (or result in a crash worse than) the economic contraction in the fall of 2008.

Alternatively, businesses, entrepreneurs and investors perceive the future deficits as an implicit promise of higher taxes, higher interest rates, or both. For any employer contemplating locating in the United States or expanding existing facilities and payrolls, rudimentary business planning reveals this to be an extremely risky environment.

But purely budget-driven arguments are insufficient to marshal support for entitlement reform. The large entitlement programs need reform in their own right. Social Security is a good example. Under current law, retirees will face a 23-percent across-the-board cut in benefits in less than two decades.[20] That is a disgraceful way to run a pension system. It is possible to reform Social Security to be less costly overall and financially sustainable over the long term.

Similar insights apply to Medicare and Medicaid, the key health safety nets for the elderly and poor. These programs have relentless appetites for taxpayer dollars yet do not consistently deliver quality outcomes. Reforms can address their open-ended draws on the federal Treasury and improve their functioning at the same time.

Growth-oriented fiscal strategy will re-orient spending priorities away from dysfunctional autopilot spending programs and toward core functions of government. It will focus less on the dollars going into programs and more on the quality of the outcomes. Such a strategy will do so because it is the principled approach, because it coincides with the best strategy to deal with the debt and growth dilemmas, and because it will force a restructuring of the entitlement programs to generate a quality social safety net.

In short, entitlement reform is a pro-growth policy move at this juncture. As summarized by AAF, research indicates that the best strategy both to grow the economy and to eliminate deficits is to keep taxes low and reduce public employee costs and transfer payments.[21]

Structural Regulation Reform

As noted above, the Trump Administration and Congress have made remarkable progress in halting the growth of the regulatory state and show promise in pursuing a regulatory agenda that should reduce net regulatory burdens. The remarkable progress on this front, however, underscores how quickly it could be reversed under another administration. There remains a need for structural regulatory reform to check the growth of the regulatory state in the future.

The Regulatory Accountability Act (RAA) is one example of how Congress can impose structural checks on future burdensome regulations. Among other provisions, the Act defines a “high-impact” rule as a measure that would impose annual costs of $1 billion and require an advanced notice of proposed rulemaking for any high-impact rule. It would also require a public hearing before adoption and for agencies to adopt rules on the basis of the best evidence and the least cost to the economy. This is one of several potential legislative efforts that could improve checks on regulatory growth.

Education Reform

K-12 education is underperforming, and reform attempts have disappointed since No Child Left Behind passed. Our economy’s future workforce is in crisis. Of 100 children born in 1983 who started kindergarten together in 1988, only 30 graduated on time in 2001. Of the 70 who eventually graduated, 50 started college, and just 28 of those 100 kindergartners had a college degree by spring of 2007. But it gets worse.

Our nation continues to report significant achievement gaps between students based on race and socioeconomic factors. On average, students of color have a much lower likelihood of graduating, at 76 percent. Of those who graduate, they typically exit high school with the functional equivalent of an 8th or 9th grade education. Despite more than $16 billion annually in targeted federal aid, our poor neighborhoods usually lack the essentials, such as good teachers. This achievement gap in the United States feeds an embarrassingly persistent and worsening gap between our students’ performance and that of students in the rest of the industrialized world. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development found that in 2012, America ranked 27th out of 34 industrialized countries in math and 20th in science.

In addition to the previously discussed policy areas, higher education requires significant reform . The amount of student loan debt has received a lot of attention, but how poorly these programs operate has received comparably little. The flaws are manifold: little-to-no meaningful underwriting at the time loans are issued, poor accounting for dollars once they are dispersed, and chronic underestimates of defaults and other taxpayer costs. In many fundamental ways, federal higher education policy looks remarkably similar to federal health policy, as both are marked by large open-ended subsidies, uneven quality, and inexorable cost growth. The federal programs that finance higher education need substantial reform, perhaps preceded by a needed assessment of the central value proposition those programs deliver.[22]

Combined, these reforms should be part of an overall workforce development agenda that also addresses other critical deficiencies in America’s workforce. While these reforms cannot fully mitigate the demographic trends contributing to the relative decline of the labor force, they can meaningfully improve the prevailing economic trend and improve the nation’s growth outlook.

Conclusion

Achieving more rapid trend economic growth is the most pressing federal policy issue. Fortunately, the roots of subpar growth are found in subpar growth policies. Focusing on permanent structural reforms to entitlement, tax, regulatory, immigration, education, and trade polices holds the promise of improving the economic outlook for this generation and those that follow.

Notes

[1] https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/demo/p60-259.html

[2] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/does-compensation-lag-behind-productivity/; Also see https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-6/below-trend-the-us-productivity-slowdown-since-the-great-recession.htm on which figure 2 is based

[3] http://americanactionforum.org/research/economic-and-budgetary-consequences-of-pro-growth-tax-modernization

[4] See: Feldstein, Martin, “The Effect of Marginal Tax Rates on Taxable Income: A Panel Study of the 1986 Tax Reform Act.” Journal of Political Economy, June 1995, (103:3), pp 551-72; Carroll, Robert, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, Mark Rider and Harvey S. Rosen, “Income taxes and entrepreneurs’ use of labor.” Journal of Labor Economics 18(2) (2000):324-351; Prescott, Edward C., “Why do Americans Work So Much More Than Europeans.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis July 2004; Skinner, Jonathan , and Eric Engen. “Taxation and Economic Growth.” National Tax Journal 49.4 (1996): 617-42; Romer, Christina D., and David H. Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks.” National Bureau of Economic Research NBER Working Paper No. 13264 July 2007 Web.http://www.nber.org/papers/w13264

[5] Altig, David, Alan J. Auerbach, Laurence J. Kotlikoff, Kent A. Smetters and Jan Walliser, “Simulating Fundamental Tax Reform in the United States.” American Economic Review, Vol. 91, No. 3 (2001), pp. 574-595

[6] https://www.wsj.com/article_email/how-tax-reform-will-lift-the-economy-1511729894-lMyQjAxMTI3MjI1NzIyMTc4Wj/

[7] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/deregulation-trump-savings-coming/

[8] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/deregulation-obama-trump/

[9] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/first-look-fy-2018-regulatory-budgets/

[10] https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/current_press_release/exh1.pdf; https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements

[11] https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/world_trade_report15_e.pdf

[12] http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/build/groups/public/@tg_ian/documents/webcontent/tg_ian_005500.pdf

[13] http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS

[14] https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/trumps-tariff-is-the-wrong-way-for-trade-enforcement-but-there-is-a-right-way

[15] https://www.usnews.com/opinion/economic-intelligence/articles/2018-03-02/trumps-steel-and-aluminum-tariffs-will-achieve-nothing

[16] Holtz-Eakin, “Immigration Reform, Economic Growth, and the Fiscal Challenge.”

[17] https://www.americanactionforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Economist_Immigration_Letter_-1.pdf

[18] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/estimating-economic-contributions-daca-recipients/

[19] https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/spec-fy2019.pdf

[20] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/future-americas-entitlements-need-know-medicare-social-security-trustees-reports/

[21] http://americanactionforum.org/insights/repairing-a-fiscal-hole-how-and-why-spending-cuts-trump-tax-increases

[22] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/priorities-reforming-modernizing-federal-financial-aid-system/

[1] https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2017/demo/p60-259.html

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/does-compensation-lag-behind-productivity/; Also see https://www.bls.gov/opub/btn/volume-6/below-trend-the-us-productivity-slowdown-since-the-great-recession.htm on which figure 2 is based

[1] See: Feldstein, Martin, “The Effect of Marginal Tax Rates on Taxable Income: A Panel Study of the 1986 Tax Reform Act.” Journal of Political Economy, June 1995, (103:3), pp 551-72; Carroll, Robert, Douglas Holtz-Eakin, Mark Rider and Harvey S. Rosen, “Income taxes and entrepreneurs’ use of labor.” Journal of Labor Economics 18(2) (2000):324-351; Prescott, Edward C., “Why do Americans Work So Much More Than Europeans.” Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis July 2004; Skinner, Jonathan , and Eric Engen. “Taxation and Economic Growth.” National Tax Journal 49.4 (1996): 617-42; Romer, Christina D., and David H. Romer, “The Macroeconomic Effects of Tax Changes: Estimates Based on a New Measure of Fiscal Shocks.” National Bureau of Economic Research NBER Working Paper No. 13264 July 2007 Web.http://www.nber.org/papers/w13264

[1] Altig, David, Alan J. Auerbach, Laurence J. Kotlikoff, Kent A. Smetters and Jan Walliser, “Simulating Fundamental Tax Reform in the United States.” American Economic Review, Vol. 91, No. 3 (2001), pp. 574-595

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/deregulation-trump-savings-coming/

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/deregulation-obama-trump/

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/first-look-fy-2018-regulatory-budgets/

[1] https://www.census.gov/foreign-trade/Press-Release/current_press_release/exh1.pdf; https://ustr.gov/trade-agreements/free-trade-agreements

[1] https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/booksp_e/world_trade_report15_e.pdf

[1] http://www.trade.gov/mas/ian/build/groups/public/@tg_ian/documents/webcontent/tg_ian_005500.pdf

[1] http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NE.EXP.GNFS.ZS

[1] https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/opinion/trumps-tariff-is-the-wrong-way-for-trade-enforcement-but-there-is-a-right-way

[1] https://www.usnews.com/opinion/economic-intelligence/articles/2018-03-02/trumps-steel-and-aluminum-tariffs-will-achieve-nothing

[1] Holtz-Eakin, “Immigration Reform, Economic Growth, and the Fiscal Challenge.”

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Economist_Immigration_Letter_-1.pdf

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/estimating-economic-contributions-daca-recipients/

[1] https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/spec-fy2019.pdf

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/future-americas-entitlements-need-know-medicare-social-security-trustees-reports/