Week in Regulation

July 1, 2019

A Heavy Volume of Minor Rules

In one of the heavier flows of such rulemakings of late, there were 19 proposed and final rules last week that included some quantifiable cost-benefit analysis. There was, however, not much to show for this series of regulations. Only four of these rulemakings even made it into the tens of millions of dollars in economic impact. Across all proposed and final rules, agencies published $80.8 million in total net costs and added 196,190 hours of paperwork.

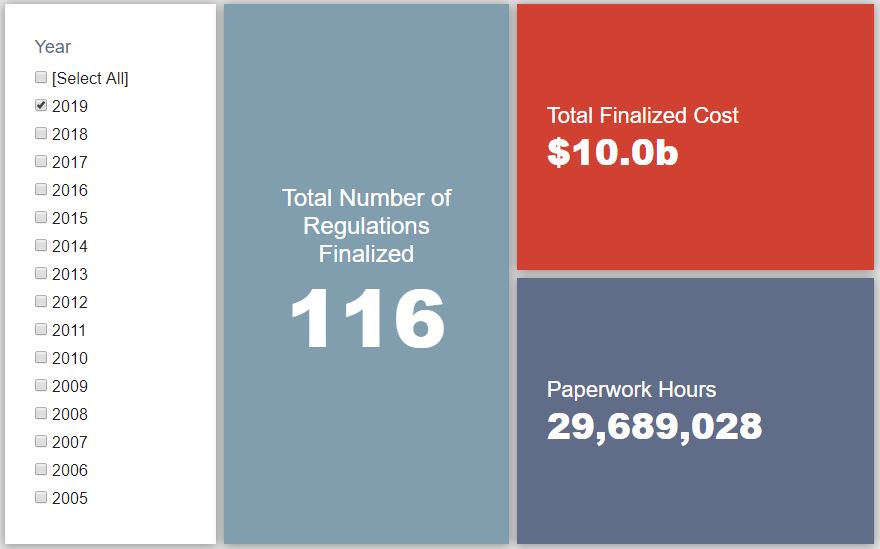

REGULATORY TOPLINES

- New Proposed Rules: 59

- New Final Rules: 73

- 2019 Total Pages: 31,108

- 2019 Final Rule Costs: $10 Billion

- 2019 Proposed Rule Costs: $1.7 Billion

TRACKING THE REGULATORY BUDGET

There was only one action that applied to the fiscal year (FY) 2019 regulatory budget under Executive Order (EO) 13,771. This final rule out of the Department of Agriculture (USDA) regarding “Plant Pest Regulations” would make some minor adjustments to the interstate transfer of certain agricultural items. Its overall impact on the regulatory budget, however, is rather small. USDA estimates that it will save roughly $55,000 annually (discounted at 7 percent in perpetuity), or nearly $786,000 in present value terms.

While it does not apply to the FY 2019 budget yet since it is still a proposed rule, the most significant rulemaking of the week came out of the Department of Labor (DOL). This proposal regarding “Apprenticeship Programs, Labor Standards for Registration, Amendment of Regulations” would establish a new framework for how certain industries could bring apprentices on board. DOL has preliminarily determined this to be a regulatory action as the administrative costs in setting up this program come out to roughly $65 million over 10 years.

So far in FY 2019 (which began on October 1, 2018), there have been 51 deregulatory actions (per the rubric created by EO 13,771 and the administration’s subsequent guidance document) against 27 rules that increase costs and fall under the EO’s reach. Combined, these actions yield quantified net costs of roughly $10.9 billion. This total, however, includes the caveat regarding the baseline in the USDA’s “National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard.” If one considers that rule to be deregulatory, the administration-wide net total is approximately $4.2 billion in net costs. The administration’s cumulative savings goal for FY 2019 is approximately $18 billion.

THIS WEEK’S REGULATORY PICTURE

This week, the Supreme Court tenuously upheld its doctrine of deferring to an agency’s interpretation of its own rules.

As the U.S. Supreme Court concluded its latest term this week, it issued a decision to uphold Auer deference, whereby courts will defer to an agency’s interpretation of its own rules in cases where a regulation is ambiguous. In doing so, however, it specified limits on that deference to such an extent that Justice Gorsuch referred to Auer as “zombified.”

The decision in Kisor v. Wilkie had little to do with the details of the case at hand. All nine justices voted to remand the case back to a federal appeals court. But the bigger question on whether Auer deference should remain the doctrine of the court resulted in a 4-1-4 split, with Chief Justice John Roberts siding with Justices Kagan, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor to uphold the doctrine, though he issued his own opinion on why Auer should remain. Justices Gorsuch, Thomas, Kavanaugh, and Alito thought it should be abandoned.

In writing for the four liberal justices, Justice Kagan defended the doctrine, saying Congress would want agencies to play a primary role in resolving regulatory ambiguities, comparing it to how one would ask the author of a memo about something in the memo that was unclear. She also emphasized some limits on Auer’s use: it should only be used when a rule is genuinely ambiguous, the agency’s reading of the rule must still be reasonable, and the agency’s interpretation must rely on its substantive expertise, among them.

Chief Justice Roberts, whose opinion is the deciding vote in favor of Auer, writes that the doctrine is precedent and there is not a novel basis for overturning it. He also opines that the effect of Auer is seldom a determining factor in a case, writing that “the cases in which Auer deference is warranted largely overlap with the cases in which it would be unreasonable for a court not to be persuaded by an agency’s interpretation of its own regulation.” He also writes that he thinks the views of the cohorts led by Justices Kagan and Gorsuch are not that far apart.

Justice Gorsuch disagreed with the prevailing view in his opinion, in which he argued that Auer deference is systematic judicial bias on behalf of the federal government and that the Supreme Court itself invented it with no direction from Congress. He further writes that Justice Kagan’s limits amount to “nebulous qualifications and limitations” in an attempt to keep Auer alive and that Chief Justice Roberts “claims to see little practical difference between keeping it on life support in this way and overruling it entirely.”

So, for now, Auer deference remains. There are two important implications of the ruling. The first is agencies will continue to have an upper hand in legal disputes over the meaning of their own rules, though the limits expressed in Justice Kagan’s opinion provide for less deference than many thought agencies had before.

The second is what it portends for more important precedent known as Chevron deference, which refers to courts deferring to an agency’s interpretation of a statute. Some Supreme Court watchers viewed the Auer case as a test of sorts to see how the court would rule on Chevron. With Auer upheld, it appears less likely Chevron will be overturned soon.

TOTAL BURDENS

Since January 1, the federal government has published $11.7 billion in net costs (with $10 billion in finalized costs) and 32.7 million hours of net paperwork burden increases (with 29.7 million coming from final rules). Click here for the latest Reg Rodeo findings.