Weekly Checkup

January 17, 2020

The Limits of Managed Care

The most politically prevalent challenge in the U.S. health care system is the cost of care, and both left and right seem to agree that managed care is a potential solution. By coordinating care among providers, managed care systems can ensure patients receive high-quality care at a lower cost. Some observational studies indicate coordinating care does indeed increase quality, but the recent results from a more rigorous study, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, appear to throw cold water on the supposed efficacy of managed care programs.

The study examined the impact of “hotspotting,” a strategy developed by the Camden Coalition that mirrors managed care programs in certain ways. Hotspotting identifies “superutilizers”—those with exceedingly high use of health care services—and connects them with an intensive, face-to-face care approach that provides the medical care, government benefits, and community services needed both to improve immediate health and to reduce future utilization of health care services. In an effort to investigate the capacity of hotspotting to improve quality of care among these superutilizers, Amy Finkelstein from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and her colleagues conducted a randomized control trial to compare health outcomes, as measured by 180-day readmission rates.

In theory, this approach to care seems worthwhile—and it follows the overall concept of managed care. Rather than allowing patients to repeat their vicious cycles of readmission for complex and chronic diseases, it swiftly identifies and enrolls them into programs that provide more comprehensive care services both inside and outside the health care system, not only minimizing their returns but promoting self-sufficiency to maintain their daily health.

But hotspotting doesn’t seem to work. After separating a control group (who received the current standard of care) from the intervention group and looking at differences in 180-day readmission rates, there was no significant difference. In an op-ed, Finkelstein notes regression to the mean as one likely reason for the negative result.

This study implicates broader health care systems and policies. Accountable Care Organizations (ACOs) and Managed Care Organizations (MCOs), forms of managed care programs within Medicare and Medicaid, respectively, aim to increase quality and reduce costs for the government using a similar system to hotspotting. Should we scrap these managed care systems because of this study?

No, but if anything this study should encourage policymakers and researchers to look at results beyond the hospital. Research indicates that the health care delivered within a hospital system accounts for, at most, 10 to 20 percent of mortality (more recent evidence places it at the low end of this range). Factors at the level of the individual and immediate community—such as health behaviors, genetics, socioeconomic status, and environmental circumstances—collectively have a far greater impact. Based on this evidence, changes to care within a hospital system will certainly help, but the impact is constrained by the proportion of hospital care’s contribution to health outcomes.

The results of this study focus on metrics within the hospital system, constricting the measure of success to an area with diminishing returns as more resources are allocated to it. Fortunately, however, ACOs and MCOs coordinate care and connect patients with resources both within and outside the hospital. The study has other limits, too. Using readmission rates as the metric of success ignores other impacts of managed care, such as potentially reducing the cost for that round of care. And the sample came only from Camden, NJ, potentially limiting the generalizability of the study.

Nevertheless, the results of this study call for a much closer look at the efficacy of such approaches to improve patient costs and outcomes. Hospital care is a large driver of health care costs, but if we want to improve outcomes while lowering costs, any effective policy will have to look beyond the walls of hospital systems.

Chart Review: Examining Medicaid Expansion

Andrew Strohman, Health Care Data Analyst

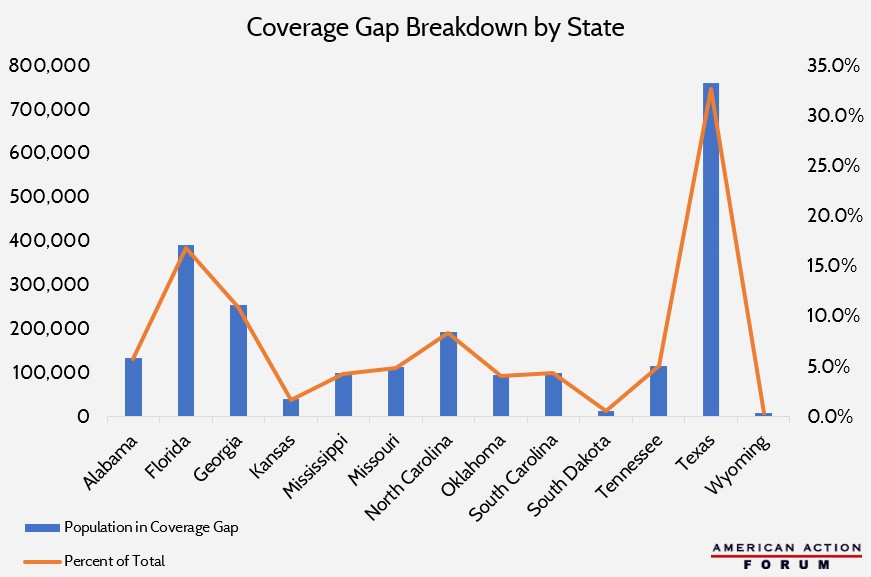

The Kaiser Family Foundation recently published a report breaking down the health insurance coverage gap. As a refresher, the coverage gap refers to individuals in non-Medicaid expansion states with income too low for Affordable Care Act marketplace subsidies but who do not qualify for Medicaid. Medicaid expansion closes this gap by expanding Medicaid eligibility effectively to all individuals at less than 138 percent of the federal poverty level, but some states have hesitated to adopt it amid concerns about the potential long-term impact on state budgets. The chart below depicts the population in the coverage gap for each state that has not expanded Medicaid. Texas contributes the largest percent of the national population in the gap at 32.7 percent (761,000 people), followed by Florida at 16.8 percent. Of note, Wisconsin has not expanded Medicaid but fills the gap with a Medicaid waiver; in other words, it solved the problem without expansion but through similar mechanisms.

Data obtained from the Kaiser Family Foundation

Worth a Look

Reuters: How Fitbits can help predict flu outbreaks

Health Affairs: Nudging Into Insurance Coverage: Lessons From 401(k) Auto-Enrollment