Weekly Checkup

January 15, 2021

The Real Failure of the Vaccine Rollout

While America’s political health has taken a nosedive recently, the nation’s physical health has entered even more precarious straights. This week saw daily COVID-19 deaths exceed 4,000 for the first time, with the new and more contagious strains of the virus appearing around the globe, including a novel mutation just found in Columbus, Ohio. These depressing recent numbers stand in stark contrast to the enthusiasm many felt in the waning months of 2020 as Pfizer and Moderna saw highly effective vaccines approved for emergency use and Trump Administration officials declared that 20 million Americans would be vaccinated by the end of the year.

The reality, however, is that just over 30 million vaccine doses have been distributed by the federal government and only 11 million people have received the first of two required vaccine injections. The obvious question is, what went wrong?

The likely answer is that the primary failure has been of managing expectations. As Kaiser Health News’ Rachana Pradhan reported this week, the obstacles to a rapid vaccination campaign are myriad. Most people are familiar by now with the cold storage challenges presented by both vaccines, but particularly the Pfizer product. The vaccines can’t be shipped in individual doses in part because of these storage constraints, and once a vial is opened all the doses must be used within roughly 6 hours or be discarded. As Pradhan reports, other factors are at play including shortages of workers, a more time-consuming process of preparing and administering the shot, and chronically underfunded and resourced state health systems. Additionally, the effort to target specific populations with early vaccination has created its own logistical challenges.

This week, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) moved to encourage states to broaden distribution beyond the first priority tier and announced that additional vaccine distribution will be weighted in favor of states that have administered higher percentages of their allotted vaccines. The latter policy could lead to unintended, albeit totally foreseeable, problems as states prioritize vaccination of populations most receptive to the vaccine and with better access to health care and information about vaccine availability. Additionally, HHS has adopted a proposal from the incoming Biden Administration to release all of the current vaccine supply for first doses, instead of holding half in reserve to guarantee those vaccinated have access to the crucial second dose. HHS maintains that there is enough vaccine in the pipeline to meet this need—but that plan contains obvious risks.

Most of the challenges that are slowing vaccine distribution were entirely foreseeable, and this underperformance fits a pattern of the last year. The Trump Administration has consistently failed to manage expectations, from “the virus will go away on its own” all the way to “we’ll have a vaccine before the end of October.” Unfortunately, President-elect Biden seems to be on a similar trajectory, as he has promised 100 million people will be vaccinated in his first 100 days in office.

It’s tempting to hope for the best, and it’s critical with a fast-mutating virus to accelerate vaccinations as much as possible. But it’s also important for policymakers, especially those at the top, to be honest with the public and remind the country that preventing the spread of the virus through social distancing, mask wearing, and other precautions will continue to be our first line of defense for some time. Better to under promise and overdeliver than give people a false sense of security and allow the virus to claim even more lives.

Chart Review

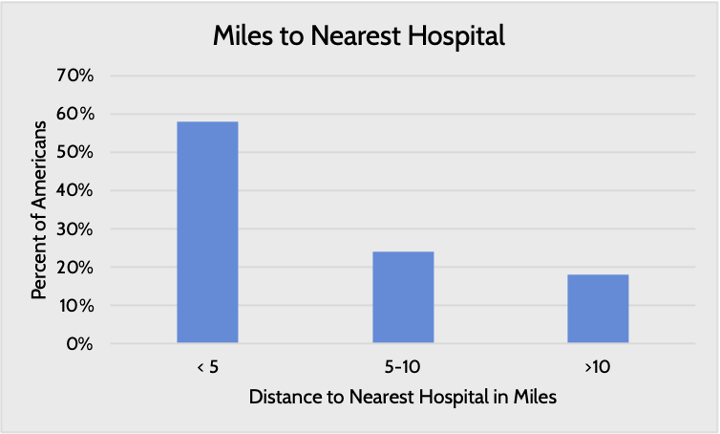

Access to quality health care can affect an individual’s awareness and control of chronic disease, and one major aspect of access is distance to care centers, write AAF’s Director of Human Welfare Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes and Serena Gillian in a recent paper. While the distance to the nearest health provider varies by region and income level (i.e. poorer and more rural individuals tend to live further away from hospitals), nearly 20 percent of Americans live more than 10 miles away from their nearest hospital. Further, large swaths of the country are designated as health professional shortage areas, whether for primary care, dental care, or mental health care, and rural areas in particular struggle with access to specialists. These access challenges are correlated with other challenges, such as poverty and pollution, that together can compound the risk of chronic disease, Hayes and Gillian argue.

Worth a Look

The Hill: Moderna CEO warns the coronavirus is ‘not going away’

New York Times: A Colonoscopy Alternative Comes Home