Insight

August 1, 2025

Is the $750B U.S.-EU Energy Deal a Fantasy?

Executive Summary

- The United States and the European Union (EU) have reached a trade agreement in which the EU pledged to purchase $750 billion worth of energy products (natural gas, oil, and nuclear fuel and reactors) from the United States over the next three years.

- Notably, the United States exported roughly $70 billion worth of energy products to the EU in 2024, and projected U.S. petroleum and natural gas exports to the bloc are about $207 billion in total for 2026–2028, meaning the EU would have to more than triple its current energy imports from the United States annually to fulfill the target.

- This insight provides a summary of the U.S.-EU energy deal, reviews the current energy market landscapes and mechanisms between the United States and EU – as well as the trade relationship – and concludes that it is very unlikely the EU will be able to fulfill the enormous energy deal target.

Introduction

The United States and the European Union (EU) reached a trade agreement on July 27. One of the most important components of this deal is the EU’s pledge to purchase $750 billion worth of energy products (natural gas, oil, and nuclear fuel and reactors) from the United States from 2026–2028.

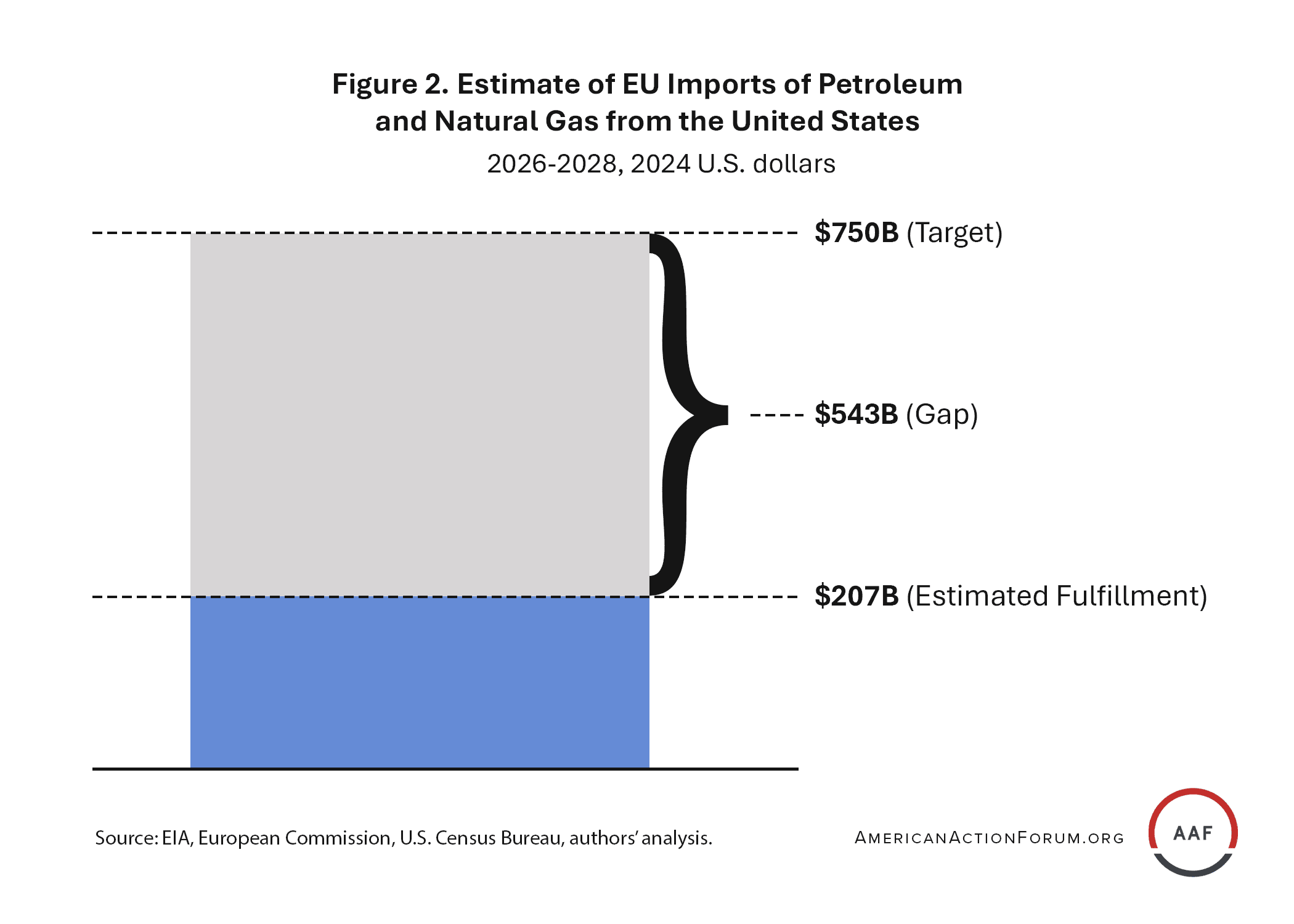

Notably, the United States exported roughly $70 billion worth of energy products to the EU in 2024, and projected U.S. petroleum and natural gas exports to the bloc are about $207 billion in total for 2026–2028, which falls nearly $543 billion short of the $750 billion target. This means the EU would have to more than triple its current energy imports from the United States annually to fulfill the target.

This insight provides a summary of the U.S.-EU energy deal, reviews the current energy market landscapes and mechanisms between the United States and EU – as well as their trade relationship – and concludes that it is very unlikely the EU will be able to fulfill the enormous energy deal target.

Summary of the U.S.-EU Energy Agreement

One of the key components of the EU-U.S. trade deal touted by the Trump Administration is the EU’s pledge to purchase more U.S. energy products. As the White House fact sheet states, “The EU will double down on America as the Energy Superpower by purchasing $750 billion of U.S. energy exports through 2028.” In a press conference after the trade deal was announced, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen commented that the EU’s energy-purchasing commitment “is divided into three years at $250 [billion] per year,” which she believes is an attainable objective. The official European Commission fact sheet reads, “the EU intends to procure US liquified natural gas, oil, and nuclear energy products with an expected offtake valued at $750 billion (ca. €700 billion) over the next three years.” An EU spokesperson clarified that nuclear energy products may include conventional and small nuclear reactors.

President von der Leyen also emphasized the fact that the EU “still [has] too much Russian LNG [liquid natural gas] that is coming through the backdoor and some Russian oil and gas,” stressing that the U.S.-EU deal is part of the effort to “absolutely get rid of Russian fossil fuels.” The European Commission’s desire to reduce reliance on Russian energy in favor of U.S. energy comes at the same time President Trump threatens to impose 100-percent secondary tariffs on countries between August 7–9. (The White House fact sheet does not explicitly specify a policy of requiring the EU to reduce reliance on Russian energy.)

It is worth noting that there is currently no formal or legally binding trade agreement signed by either party, with multiple points of contention that still must be ironed out. According to an EU official, both sides are working on a legal framework, but the content has yet to be confirmed. Any forthcoming framework will require a majority of EU member countries to ratify, meaning it may be months or years before a final, binding trade deal is completed.

Overview of U.S.-EU Energy Trade

The EU imported roughly €375 billion worth of energy products from the rest of the world in 2024, equivalent to about $430 billion.

As shown in Figure 1, the United States exported roughly $70 billion of energy products to the EU in 2024, accounting for 18 percent of total EU energy imports in the same year. While U.S. energy exports to the EU have increased significantly from 2022–2024, mostly driven by the substantial increase in natural gas exports after Russia invaded Ukraine in 2022, the annual $250 billion target from 2026–2028 seems unrealistically high. The EU would need to more than triple its energy imports from the United States in 2024 to reach the target.

Source: European Commission

Note: The “other energy products” category includes coal, lignite, peat, and coke imports.

Total imports of petroleum and natural gas from the United States are projected to be $207 billion (in 2024 dollars) from 2026–2028 based on the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) forecast. This number falls significantly short of the $750 billion target with an enormous gap of $543 billion to be fulfilled (see Figure 2). Note that this estimate does not include any U.S. nuclear fuel or reactor exports to the EU.

Why Is the Deal Difficult to Fulfill?

The EU’s ambitious promise of purchasing $750 billion worth of energy products from the United States over the next three years seems highly unlikely to be fulfilled for the following reasons.

Oil and gas market mechanisms

U.S.-EU trade in oil and natural gas products is determined by the energy demand of the EU, the supply of U.S. energy production, and the global oil and gas market trends. The European Commission cannot dictate how many energy products the bloc purchases from the United States, as it is market actors (mostly EU businesses) that import oil and gas products from foreign markets.

EU importers have existing long-term energy contracts with other countries such as Norway and Kazakhstan for oil and gas purchases. It is not realistic or feasible for the importers to breach the existing contracts and switch those purchases to U.S. exports. Additionally, the EU’s geographical proximity to countries such as Norway and the United Kingdom makes it easier to import energy products from those markets using existing infrastructure.

U.S. oil and gas producers make investment decisions to increase their production mainly driven by the demand and returns on investment. The vague and not legally binding energy deal is not likely to have material impact on U.S. oil and gas production.

Additionally, U.S. LNG export terminals are already running at full capacity. Building new energy export infrastructure is both costly and slow. It costs tens of billions of dollars and takes years to build a new natural gas export terminal in the United States. For example, the recent announcement of a terminal for natural gas exports to Europe is expected to cost more than $15 billion and will take two years before it begins to deliver energy to the EU.

The EU’s declined energy imports from Russia

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU has dramatically reduced its energy imports from Russia from $124 billion in 2022 to $25 billion in 2024 (see Figure 3). Even if the EU were to cut its energy imports from Russia entirely and fulfill the demand with U.S. exports, it would only add $20 billion annually to the purchase amount.

Source: European Commission

U.S. nuclear exports

There is also significant uncertainty about how much the EU nuclear products imported from the United States would contribute to the total amount of energy purchase.

U.S. nuclear developers import almost all of the uranium concentrate they used in nuclear reactors in 2023 from countries such as Canada, Australia, and Kazakhstan. In the same year, the United States only produced 0.05 million pounds of uranium concentrate U3O8, whereas it imported 32 million pounds of the same type of uranium.

It’s unclear how much nuclear fuel the EU will be able to purchase from the United States given the latter is a major importer of uranium. Additionally, the Trump Administration has adopted executive actions to boost the U.S. nuclear energy industry, which would, at least in theory, further increase domestic consumption of any domestically produced nuclear fuel.

Although the EU has indicated it is also interested in purchasing both conventional and small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) from the United States, this would not likely lead to a significant contribution to the target. From 2018 to 2023, total U.S. exports of nuclear equipment were about $2 billion, which is a negligible amount compared to the magnitude of the energy deal target. The United States also lags behind China and Russia significantly in terms of nuclear design exports, with no reactors currently being constructed in foreign markets with U.S. design. SMRs are under development in the United States, which makes exports of the SMR technology to the EU within the next three years challenging.

Global energy prices

The degree to which the EU can live up to the expectations of this deal will also heavily depend on energy prices, particularly natural gas and oil, given the fact the arrangement does not factor in energy volumes. This means that a sharp increase in energy prices – whether that be due to a geopolitical event or other market factors – makes the $750 billion goal easier to achieve. The reverse – that falling energy prices will make the deal harder to uphold – holds true as well. Additionally, the EU factsheet explicitly states that the $750 billion figure is the expected offtake value, which will include transportation costs rather than just the raw value of energy products. If the shipping costs rise unexpectedly or remain elevated as they have been in recent years, this will push the EU closer to the target.

Non-legally binding agreement

The U.S.-EU energy deal is also challenging to fulfill as it is not a legally binding agreement. There are no effective mechanisms to enforce the fulfillment of the target. For example, during President Trump’s first term, the administration negotiated a trade deal with China in January 2020 to de-escalate the U.S.-China trade war, which started in 2018. As part of the trade deal, China agreed to purchase additional U.S. goods and services worth $200 billion from 2020–2021 compared to the 2017 baseline level, whereby the total committed imports amounted to $502 billion. Yet China ended up importing only $290 billion over the two-year period, just 58 percent of the overall committed amount.

Conclusion

In view of the U.S.-EU energy market landscape and trade relationship, it is very unlikely that the EU will be able to fulfill the enormous energy deal target within the next three years. The agreed upon number of $750 billion seems to be symbolic rather than practical.