Insight

December 5, 2024

Lowering the Cost of the Universal Service Fund

Executive Summary

- The Universal Service Fund (USF) provides subsidies for both broadband deployment and affordability, but with the program’s funding mechanism relying on a decreasing base, there are calls for reforms that could require that broadband services or “big tech” pay into the fund.

- While USF likely needs some reform to its contribution mechanism, it is important to note that the total cost of the program has increased over time because it was extended to cover broadband services, even while many of the USF programs overlap with a variety of other broadband support subsidies.

- As the incoming Congress considers USF reforms, it should look to lower the costs of USF’s deployment and affordability subsidies, thereby reducing the strain on the contribution side.

Introduction

The Universal Service Fund (USF) was created to provide telephone service to all Americans and, over time, expanded to provide support for the deployment and adoption of broadband services. Yet expanding the program to support broadband has increased the costs of the program, putting an increased strain on the traditional telephone subscribers who fund it.

Since 2023, a bipartisan group in Congress has been working with industry, academia, and public interest groups to reform the program. A major focus of these discussions has been on the contribution mechanism – how to fund the program – and suggested reforms would potentially expand the contribution base to include broadband services or profits from “big tech” that benefit from USF infrastructure. Before even looking at contributions, however, Congress should consider whether its distributions need reform: If Congress can lower the costs of the program, the funding requirements will likewise be reduced.

Currently, the Universal Service Fund costs over $8 billion a year. Most of these costs come from deployment subsidies in the “High Cost” program and the schools and libraries support mechanism, “E-Rate.” The need for such subsidies, however, is now in question, in part because deployment subsidies have been made duplicative by significant investment from the Broadband, Equity, Access and Deployment (BEAD) program and the deployment of low-earth orbital satellite systems that can cover the most difficult-to-reach locations. As Congress considers reforms to the USF funding mechanism, it should first focus on limiting the program’s costs.

USF and its Funding Issues

USF was first created to subsidize the deployment of voice telephone service to low-income households and high-cost areas but was later expanded to provide support for rural health care providers and schools and libraries. USF has been also extended to provide support for broadband services.

USF consists of four programs. First, the High-Cost Support Mechanism, now known as the Connect America Fund, provides subsidies for the deployment of broadband to high-cost areas, which are typically rural. Second, the Lifeline program provides low-income consumers with a monthly $9.25 subsidy for their broadband service, and a monthly $34.25 for low-income consumers on tribal lands. Third, the schools and libraries support program, E-Rate, provides support to schools and libraries to obtain affordable broadband. Finally, the Rural Health Care program provides funding to eligible health care providers for telecommunications and broadband services necessary for the provision of health care.

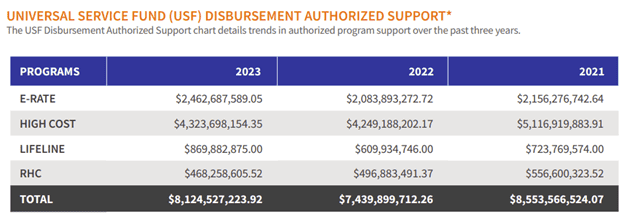

In 2023, USF distributed around $8.1 billion, with the majority of these distributions – over $4 billion – going to the High-Cost program. About a quarter of the USF’s distributions – $2.4 billion – went to the E-Rate program, and the Lifeline and Rural Health Care programs received $869 million and $468 million, respectively.

To support the program, telecommunications subscribers pay a percentage fee on their bill every month. Since transitioning to support broadband, USF costs have increased dramatically, but the number of telecommunications subscriptions has decreased. As a result, those consumers still subscribing to telephone services must pay a much larger percentage of their bill in fees. In 2000, the contribution factor was around 5.7 percent. Today, it is 35.8 percent.

Efforts to Reform USF Funding

The current structure of USF places a significant burden on traditional telecommunications subscribers. As a result, there have been a variety of calls to reform the program, specifically with regard to which services can be assessed and therefore which subscriptions will see a USF fee. Under current law, only telecommunications services can be included, so information services like broadband are not.

One proposal is for the USF contribution base to include broadband services, as they are now subsidized by the program. The Federal Communications Commission (FCC) could theoretically assess broadband if it designates broadband as a Title II telecommunications service, but even when the FCC did so in the past, it refused to extend the contribution base to broadband subscriptions. What’s more, the FCC’s authority to reclassify broadband at all is in serious doubt due to ongoing litigation and significant doctrinal changes in the courts.

More recently, some commentators including FCC Chairman-designate Brendan Carr have called for the inclusion of “big tech” into the USF contribution base. Under this theory, those services that benefit from the subsidization of broadband should contribute to it, but the exact structure of such a proposal is unclear.

Regardless, to reform the contribution mechanism, Congress would likely need to pass legislation giving the FCC additional authority. In Congress, a bipartisan working group has been considering reform to the USF program since 2023 and will likely continue in the new Congress.

Where Congress Should Focus: Distributions

While the contribution discussion has received the most attention, Congress and the FCC should instead start with reforms to limit USF distributions. If regulators can lower the overall cost of the program, the contribution factor will likely decrease as well. And while universal service is a laudable goal, waste from overlapping programs, as well as fraud and abuse in USF, could be reduced to maximize the program’s benefits while minimizing its costs.

For example, High-Cost support receives over half of the current distributions. Meanwhile, however, Congress has spent more than $42.5 billion on the BEAD program to provide universal broadband connectivity in the United States. Much of the High-Cost distributions are part of ongoing commitments, and thus difficult to alter. But there are areas in which the FCC can reduce waste, fraud, and abuse, and in particular make reforms to ensure that a technology-neutral approach to broadband connectivity provides universal service at minimal cost. Further, to the extent that any funding for new builds is still available, the FCC could begin to wind down the program entirely.

Further, waste in programs such as E-Rate reduces the value of funds going to schools and libraries. For example, recent changes to the E-Rate program allow schools and libraries to use E-Rate funds on Wi-Fi routers for school buses, raising significant criticism from Republicans that this was both ineffectual and duplicative. First, it is unclear whether Wi-Fi on school buses actually helps children with their studies and could indicate that some schools are receiving more funds than necessary to achieve the objectives of the program. Second, Congress created the $7.2 billion Emergency Connectivity Fund during the COVID-19 pandemic to support students learning outside of the classroom – and this program specifically provided $60 million for Wi-Fi on school buses. Such wasteful overlap could be eliminated relatively easily.

Finally, while the FCC has reformed the Lifeline program to eliminate waste, fraud, and abuse, there are still many instances in which the program has been exploited. For example, the FCC recently found that a Florida company had stolen more than $100 million from the program over eight years. In other cases, price isn’t a primary factor in whether a household would choose to subscribe to broadband, and perhaps the Lifeline’s eligibility criteria could be revisited to ensure that only those households that truly need support receive it.

Conclusion

The USF program serves an important role in ensuring that all Americans have access to high-speed, quality broadband. While the Congress should consider reforms to the contribution mechanism to ensure the fund can be sustainable, the more prudent course of action is to first focus on distributions. With so many broadband subsidy programs currently available, many with overlapping goals and functions, it is incumbent on Congress and the FCC to limit distributions to those that are necessary to achieve universal service, thereby limiting the overall burden on consumers.