Research

September 10, 2024

Destroying De Minimis

Executive Summary

- Federal lawmakers are considering legislation that would alter or effectively eliminate the use of de minimis, a U.S. trade rule that allows imports valued below $800 to enter the United States free from tariffs and added fees.

- The primary argument for restricting what critics call the “de minimis loophole” is that it disfavors U.S. trade interests and allows a path for illicit drugs and counterfeits to enter the country; nevertheless, these arguments ignore the extent to which data collection already takes place and fail to weigh the economic harms that would result from eliminating this rule.

- The full elimination of de minimis would impact more than 1 billion shipments – in total, valued at $54 billion – and would result in $8 billion to $30 billion in additional annual costs that would eventually be passed on to consumers; eliminating de minimis would also harm small businesses, which would be forced to absorb these costs or else lose customers, as well as damage trade relations by encouraging retaliation.

Introduction

Federal lawmakers are considering legislation that would alter or effectively eliminate a section of U.S. trade law known as “de minimis,” which allows shipments valued under $800 to enter the United States duty-free. Members on both sides of the aisle argue that closing the “de minimis loophole” through increased data collection and limiting its use would promote trade fairness, limit the flow of illicit drugs, and crack down on counterfeit goods. While these are valid concerns, the vast majority of narcotics that result in fatal overdoses enter via the southern border and intellectual property seizures represent a tiny fraction of the total value of shipments entering via de minimis. As for trade fairness, many countries do, in fact, have a lower de minimis threshold than the United States, which may put U.S. exports at a disadvantage in foreign markets. Lowering the U.S. de minimis threshold to match that of other countries, however, would place a greater financial burden on consumers who would then have to pay additional fees and tariffs.

This research finds that eliminating de minimis in the United States would result in between $8 billion and $30 billion in additional annual costs for consumers and taxpayers.[1] This is the equivalent of a 14 percent to 55 percent import tax on more than 1 billion de minimis shipments valued at $54 billion. These shipments, primarily purchased by low-income households, would then face increased screening by U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP), thereby adding to shipment wait times and straining the already short-staffed agency.[2] Furthermore, de minimis encourages importers and producers to lower prices below the threshold to save on fees, paperwork, and tariffs, which adds to consumer savings. Without the de minimis threshold, administrative and tariff costs would increase substantially, ultimately being passed on to U.S. consumers in the form of higher prices.

Defining De Minimis

De minimis shipments, known formally as Section 321 entries, are U.S. imports with a value up to $800 that are essentially exempt from administrative and processing fees, as well as most U.S. duties. This policy was first implemented in the 1930s and updated in 2016 to raise the de minimis threshold from $200 to $800. Current de minimis rules allow low-value imports to enter the United States duty-free, in large part because the paperwork needed to process the duties often costs more than the duties themselves.[4] A National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) paper estimates that per-shipment administrative fees could rise from $0 to over $23 with the removal of de minimis.[5]

While there may be a misconception that these de minimis packages are unrestricted and unregulated in the import process, there are indeed exceptions and guidelines that govern them. Shipments are screened by CBP and a manifest must be physically or electronically presented to ensure a record of key data points, such as package value, the recipient’s name, addresses, product descriptions, and carrier information.[6] Electronic filing utilizes the Automated Manifest System, which tracks this data but not the Harmonized Tariff Schedule (HTS) codes used to classify products for the purpose of applying tariffs. Electronic filing was made available to all carriers via the “Type 86” pilot, which made up 62 percent of de minimis shipments as of 2023. The Type 86 entry process requires HTS codes to be documented.[7] These HTS codes are a major requirement in current legislation, but it is unclear whether they provide any value in identifying illicit goods as their intended function is identification for revenue collection (see appendix).

Figure 1: Comparing Types of Import Entries

| Import Category |

De Minimis |

Informal Entry |

Formal Entry |

| Value |

$0 to $800 |

$801 to $2500 |

Over $2500 |

| Processing and Administrative Fees |

$0 |

$2.22 to $9.99 |

$31.67 to $614.35 |

| Tariffs Applicable |

No |

Yes |

Yes |

| Bond Required |

No |

No |

Yes |

| Seller/Carrier/Recipient Information |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Addresses |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| Product Description |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

| HTS Code Listed |

62% |

100% |

100% |

| Penalties for Rule Breaking |

Yes |

Yes |

Yes |

Source: The Value of De Minimis Imports; National Foreign Trade Council; GHY International; NNR Global Logistics

It is also worth noting that the $800 de minimis threshold for shipments is a per-day limit. This means that no matter how many small shipments an individual orders, their sum cannot exceed $800 in value in one day, otherwise the additional shipments will not qualify. Additionally, a single order is not allowed to be split up over multiple days to avoid hitting the $800 limit, meaning a $1,000 package cannot be split into $500 one day and $500 the next day. Any attempt to circumvent these rules or undervalue a product is subject to fines and other legal penalties. Furthermore, any package with a product that is subject to U.S. antidumping duties (e.g., steel) does not qualify, nor do goods regulated by other government agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration.

Demarking the Merits of De Minimis

As of May 2024, more than 700 million de minimis packages have entered the United States, with a combined value of roughly $33 billion.[8] If trends continue for the remainder of the year, there could be as many as 1.6 billion packages that enter the United States in 2024 valued at $78 billion. A more conservative estimate puts 2024 de minimis shipments at 1.3 billion packages valued at $61 billion by year’s end. These de minimis shipments constitute no small component of U.S. trade, representing an average of eight packages worth more than $400 per U.S. household given 2023 figures.[9] Using the calculated trends above, these shipments could average as many as 13 packages valued at $600 for every U.S. household.

Figure 2: Value of De Minimis Entries Over Time

| Year |

2012 |

2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 | 2021 | 2022 |

2023 |

| Value per Entry |

$0.45 |

$0.59 | $6 | $12 | $41 | $39 | $71 | $112 | $105 | $56 | $68 |

$51 |

Source: The Value of De Minimis Imports; CBP 2023 Trade Fact Sheet

Figure 3: 2021 Impacted Countries and Respective De Minimis Thresholds

| Country |

De Minimis Shipments |

2023 Estimated Value

($ millions) |

Potential Tariffs

($ millions) |

De Minimis Value for the U.S. |

| China |

62% |

$33,790 | $5,069 |

$7 |

| Canada |

8% |

$4,360 | $92 |

$111 |

| U.K. |

7% |

$3,815 | $80 |

$178 |

| Mexico |

3% |

$1,635 | $34 |

$50 |

| Germany |

1% |

$545 | $11 |

$168 |

| Other |

19% |

$10,355 | $217 |

Average: $124 |

| Total |

100% |

$54,500 | $5,503 |

Average: $128 |

Source: Section 321 De Minimis Shipments FY 2018 to 2021; De Minimis Threshold Table; GEA De Minimis Country Information

As of 2023, China was the primary country of origin for de minimis shipments, making up three out of every five shipments, which is down from three out of every four shipments in 2018.[10] Figure 3 displays the other major countries that utilize de minimis as well as the $5.5 billion in potential tariff costs that would be imposed without this policy.[11] Each of these countries, along with about 140 others, have definitive de minimis thresholds of their own.[12] The average and median threshold for these countries is $128 and $84, respectively, well below the $800 in the United States. While this means that U.S. exporters face a far tighter de minimis limit than foreign competitors, U.S. consumers benefit from lower prices on imported products. Moreover, altering or eliminating de minimis in the United States would almost certainly be met with retaliation from trading partners, who would likely eliminate their de minimis thresholds altogether. This would ultimately make low-value U.S. exports more expensive due to added tariffs and reduce U.S. competitiveness.

De minimis also has strong implications for lower-income consumers, as they disproportionately rely upon cheaper shipments that fall under de minimis.[13] The elimination of de minimis would increase the average tariff on the poorest ZIP codes from 0.5 percent to 12 percent, while the richest ZIP codes would face an average tariff of 7 percent, up from 1.5 percent. This disparity demonstrates that de minimis is most beneficial for lower-income consumers. De minimis also helps small businesses compete with much larger companies in international markets as it eliminates excessive administrative, tariff, and regulatory costs. By eliminating de minimis, businesses would either have to absorb these costs, lowering profits, or pass them on to consumers, who would then search for cheaper alternatives.

Notably, the de minimis rule encourages producers, sellers, and carriers to keep prices below the $800 threshold. This means that sellers often reduce the prices of goods that would otherwise be just above $800 to save on various fees, translating into lower prices for consumers.[14] Removing the de minimis threshold would also remove the incentive for importers to lower prices and instead drive price increases to compensate for new cost burdens.

Legislation to Restrict or Eliminate De Minimis

Lawmakers on both sides of the aisle are seeking to close what they consider to be the “de minimis loophole” in five notable bills, with three in the Senate and two in the House (see appendix for details). The common themes of the legislation include increased data collection on shipments, eliminating the de minimis classification for some or all types of goods from certain countries, and bolstering penalties for those who do not comply with regulations. While the bills differ in approach, the modifications to limit or outright eliminate the $800 de minimis threshold are in large part rationalized by concerns that it creates a pathway for illicit drugs and counterfeit goods.

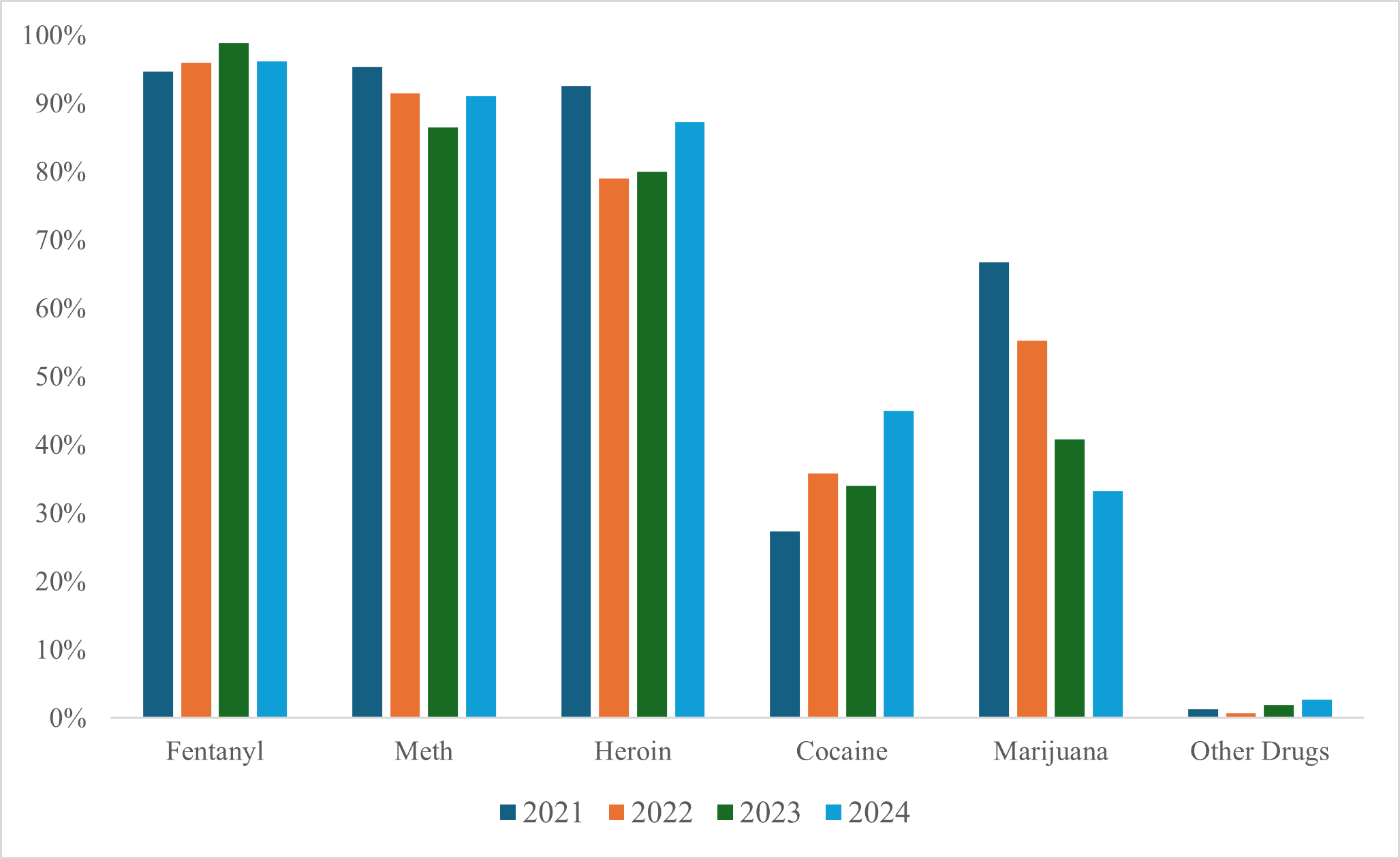

One of the key concerns surrounding de minimis is that it creates a pathway for illicit drugs to enter the country. Figure 6 examines illicit narcotics data from CBP and shows that nearly all illicit drugs, specifically those that account for the vast majority of overdose deaths, are seized at the southwest border of the United States, including 99 percent of fentanyl, the leading cause of overdose deaths.[15] Even when looking at de minimis-specific seizure data from CBP, narcotic seizures make up just 21 percent of all de minimis seizures as of 2021.[16] This figure raises the question of how efficient limiting de minimis would be for the purpose of reducing the flow of dangerous drugs. Further scrutiny of de minimis shipments could have an impact on seizures of cocaine, marijuana, and other drugs but likely minimal downstream effects on overdose-related deaths.

Figure 6: Percent of Illicit Drug Seizures at the Southwest Border

Source: CBP Drug Seizure Statistics

The other main argument for restricting de minimis is that it would combat intellectual property theft and counterfeits. While there is no direct measurement of de minimis counterfeit seizures on the CBP dashboard, mail and express consignment can act as an imperfect substitute since that is the primary mode of de minimis transport. Figure 7 demonstrates that while mail and express seizures account for about 40 percent of the total value of counterfeit seizures, this is less than 3 percent of the total value of all de minimis shipments. Therefore, eliminating de minimis could help prevent the flow of counterfeits but at the expense of the other 97 percent of total value shipped under the rule.

Figure 7: Intellectual Property Seizures Over Time

| Year |

Total Unique Seizure Value ($ millions) |

Mail and Express Seizure Value (Portion of Total Value) |

Mail and Express Seizure Value (Portion of De Minimis Value) |

| 2019 |

$1,555 |

47% |

1% |

| 2020 |

$1,309 |

52% |

1% |

| 2021 |

$3,330 |

38% |

3% |

| 2022 |

$2,981 |

46% |

3% |

| 2023 |

$2,759 |

41% |

2% |

Source: CBP Intellectual Property Rights Seizures

The Cost of Altering De Minimis Policy

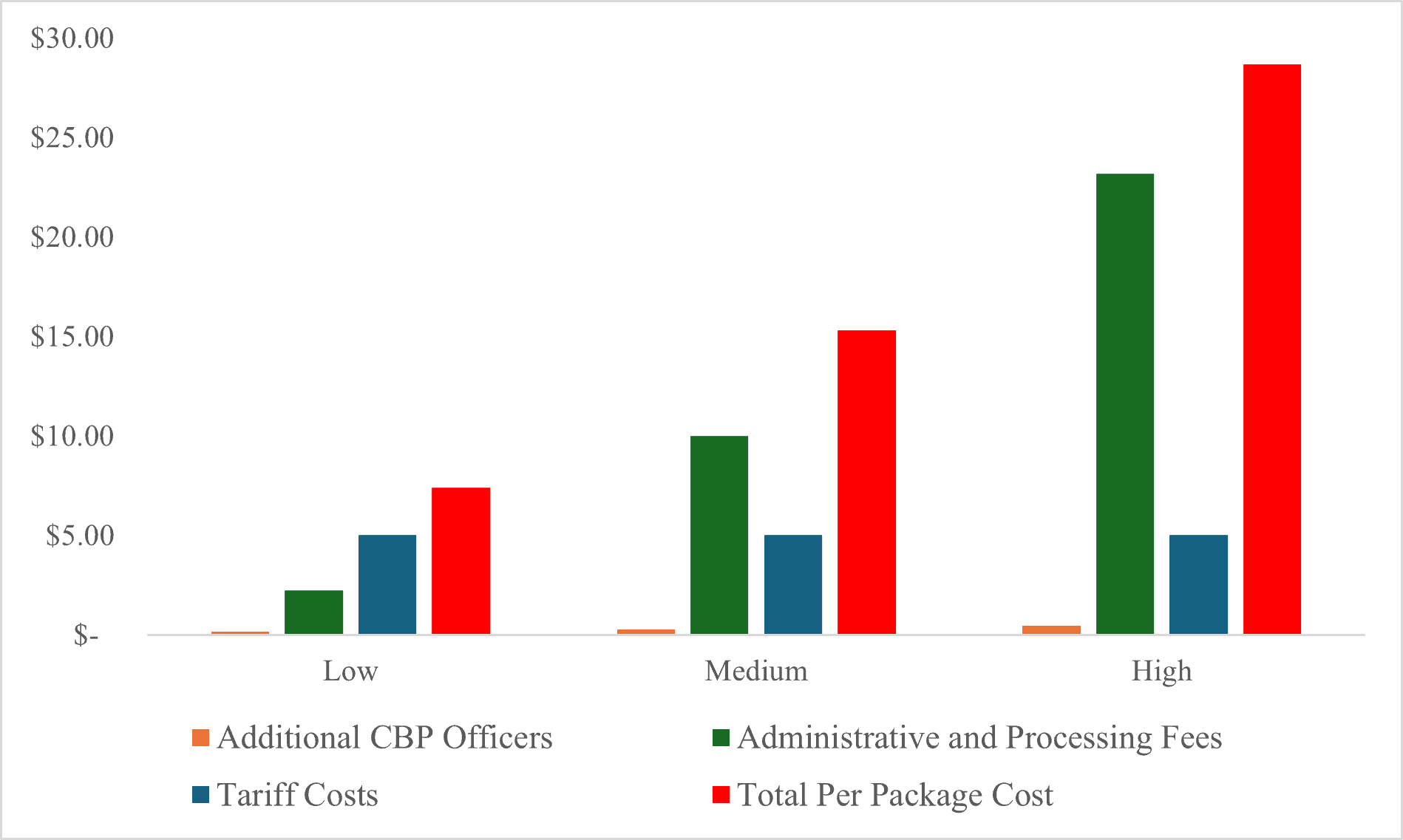

It is difficult to predict both the federal spending and consumer costs for each of the proposed bills. While the End China’s De Minimis Abuse Act has a Congressional Budget Office direct-spending estimate of $48 million over five years, on the consumer and producer side, there is an additional $10 billion in costs (in the form of projected revenue). Since many of the bills effectively eliminate the benefits of de minimis, it is most reasonable to estimate the cost range assuming the rule was fully dismantled. This study estimates a range of roughly $8 billion to $30 billion in increased annual costs that would be passed along to consumers and producers in the form of higher prices for goods and added fees on imports. This estimate, per a recent NBER paper, assumes an average tariff value of 15 percent on Chinese imports and 2.1 percent on all other imports, with approximately 60 percent of de minimis imports coming from China.[17] Additionally, it uses a range of potential administrative fees that would take effect as indicated by the CBP and other studies. Altogether, the added cost is equivalent to placing a tax of between 14 percent and 55 percent on low-value shipments that have an average value of $51.

Figure 8: Annual Cost Estimate of Eliminating De Minimis with no Further CBP Investment

|

Low |

Medium |

High |

|

| Total Cost ($ millions) |

$7,729 |

$16,012 |

$30,083 |

| Per-shipment Cost |

$7.25 |

$15.02 |

$28.22 |

| Cost as a Percent of Average Shipment Value |

14% |

29% |

55% |

Source: The Value of De Minimis Imports; Calculations performed with given data

Notably, the above estimates do not factor in the increased demands on CBP that would arise resulting from the elimination of de minimis, given there would be 1 billion additional packages to screen every year. As CBP currently has a staffing shortage of between 1,700 and 2,300 officers, hiring enough staff to fill the current gap would require about $175 million in annual salaries and represent an almost 4 percent increase in CBP staff.[18] To account for the added burden of processing formerly exempt de minimis shipments, this research’s medium estimate would increase staff levels by 6 percent and the high estimate would increase staffing by 10 percent. The National Foreign Trade Council’s estimates are even greater, stating that up to 22,000 additional staff would be needed to address de minimis shipments.[19] These estimates do not account for the additional screening devices and training costs required.

Figure 9: Annual Cost Breakdown by Category with Additional CBP Officers ($ millions)

|

Low |

Medium |

High |

|

| Total Cost |

$7,903 |

$16,314 |

$30,567 |

| Administrative and Processing Fees |

$2,367 |

$10,649 |

$24,721 |

| Newly Applied Tariffs |

$5,363 |

$5,363 |

$5,363 |

| Additional CBP Agents |

$174 |

$302 |

$483 |

Source: CBP Careers; Border Patrol Salary Data; The Value of De Minimis Imports

Figure 10: Cost Per Shipment Breakdown by Category

Source: See Figure 9

The exact administrative and processing fees de minimis shipments would face is unknown but they could face the same fees as informal entries ($801 to $2500) which is roughly $2.22 to $9.99 (see Figure 1).[20] Other studies estimate a benchmark cost of between $23.19 and $47.23 per shipment, which includes broker fees, merchandise fees, and other regulatory burdens.[21] Without the intentional lowering of fees for shipments that would have otherwise entered under de minimis, costs will dramatically increase for small packages coming into the United States, equating to higher prices for U.S. consumers. The costs mentioned above are not the only concerns regarding the removal of de minimis. There would also be increased regulatory paperwork, additional compliance penalties, and new strains on supply chains due to added wait times at ports of entry.

Conclusion

The full elimination of de minimis would impact more than 1 billion shipments – in total, valued at $54 billion – and would result in $8 billion to $30 billion in additional annual costs that would eventually be passed on to consumers. Eliminating de minimis would also harm small businesses, which would be forced to absorb these costs or else lose customers, as well as damage trade relations by encouraging retaliation.

Appendix

The De Minimis Reciprocity Act of 2023:[22] This bill was introduced on June 14, 2023, and primarily seeks to promote reciprocity with trade partners, meaning that the United States de minimis threshold would be adjusted to match the thresholds of other countries up to $800. New tariff revenue resulting from the adjustments is intended to be made available for the purpose of facilitating the movement of manufacturing from China to the United States via the new “Re-shoring and Near-shoring Account.” It explicitly excludes China and Russia from de minimis shipments and leaves the door open for other countries to be prohibited depending on whether they are known to export counterfeits. Additionally, countries may be removed from de minimis treatment if they are not to combating illegal narcotics, human trafficking, or terrorism, which is determined by human trafficking reports and the State Department, as well as at the Treasury secretary’s discretion. Furthermore, the bill would require HTS codes on shipments, along with numerous other data points, nearly all of which are already recorded.

The Import Security and Fairness Act:[23] This bill was introduced on June 15, 2023, in both the House and Senate and would remove all non-market economies alongside five priority watchlist countries from receiving de minimis treatment. The bill would require HTS codes for shipments along with descriptions, identifications, and other data points that are already gathered under de minimis. It would also strengthen penalties for violating any regulations and restricts anyone who is suspended from doing business with the U.S. government from utilizing de minimis.

Ensure Accountability in De Minimis Act of 2024:[24] This bill was introduced on April 9, 2024, and would restrict the use of de minimis to international mail, the owner of the good, or certain designated customs brokers. This legislation could potentially restrict the size of packages coming into the United States as well as heavily limit the mode of transport to primarily U.S. citizens who are returning from abroad. The bill would update penalties for fraud or negligence to abide by regulations and calls for enhanced data collections on de minimis shipments in consultation with the commissioner of the CBP. It also calls for a report by the CBP and Treasury one year after enactment that provides details regarding shipment seizures.

End China’s De Minimis Abuse Act:[25] This bill was introduced on April 17, 2024, and formally considers de minimis to be a “privilege” rather than a component of trade law. It would eliminate de minimis for any good that is subject to anti-dumping duties or tariffs (Section 301, 232, 201). It would require HTS codes for all de minimis shipments and add heavy penalties for violations of de minimis regulations or CBP procedures. This is the only bill that has a Congressional Budget Office score, with an estimate of $48 million in spending and $10 billion in revenue (tariff costs on U.S. consumers) from 2024 to 2029.

The FIGHTING for America Act of 2024:[26] This bill was announced on August 8, 2024, but has not yet been introduced in committee. Its primary purpose is to curb the importation of illicit goods. It would bar de minimis use for goods that are “import-sensitive” (goods including certain textiles, clothing, steel, electronics, and numerous other items[27]), subject to anti-dumping duties, subject to tariffs (under Section 301,232, 201), identified as experiencing an import surge, or present a persistent risk of illegal importation. While this would severely restrict the use of de minimis, the bill would also implement a $2 per-shipment fee intended to offset increased CBP screening and administrative costs. The HTS codes for shipments would be required along with additional documentation, most of which is already recorded. Additionally, the bill lays out additional penalties for violating de minimis rules and regulations.

Figure 4: A Comparison of Legislation on De Minimis

|

Bill |

Main Sponsors | Enactment Timeline | Penalties for Violations |

|

De Minimis Reciprocity |

Senator Cassidy (R)

Senator Baldwin (D) Senator Vance (R) |

Within 180 days |

None Outlined |

|

Import Security and Fairness |

Rep. Blumenauer (D)

Rep. Dunn (R) Senator Brown (D) Senator Rubio (R) |

Within 180 days |

First: $5,000 Other: $10,000 |

|

Ensure Accountability in De Minimis |

Senator Braun (R)

Senator Baldwin (D) |

Within 60 days |

Impact on Duties Either: 10x the duty value or $2,000

No Duty Impact Either: 200% of the package value or $2,000 |

|

End China’s De Minimis Abuse |

Rep. Murphy (R)

|

Within 30 days |

First: $5,000 Other: $10,000 |

|

FIGHTING for America |

Senator Wyden (D) Senator Lummis (R) Senator Brown (D) Senator Collins (R) Senator Casey (D) |

Within 180 days |

Violation First: $1,000 Other: $5,000

Fraud First: $5,000 Other: $10,000 |

Figure 5: Adjustments to De Minimis by Bill

|

Bill |

Major Alterations |

Data Requirements |

| De Minimis Reciprocity |

|

New

Already Recorded

|

| Import Security and Fairness |

|

New

Already Recorded

|

| Ensure Accountability in De Minimis |

|

Further regulations developed in consultation with multiple parties to avoid redundancy

Publish a report on seized shipments with relevant data |

| End China’s De Minimis Abuse |

|

New

|

| FIGHTING for America |

|

New

Already Recorded

|

[1] De Minimis Value (trade.gov); Section 321 Programs | U.S. Customs and Border Protection (cbp.gov)

[2] The Value of De Minimis Imports | NBER

[3] The De Minimis Exception: A Not-So-Minimal Loophole to Trade Policy | International Law and Policy Brief (gwu.edu)

[4] Key Trade Issues in USICA and COMPETES: The Good, Bad, and Ugly – AAF (americanactionforum.org)

[5] The Value of De Minimis Imports | NBER

[6] New De Minimis One Pager (nftc.org); Understanding the Differences Between Section 321 and Entry Type 86 – GHY International

[7] Understanding the Differences Between Section 321 and Entry Type 86 – GHY International

[8] The Value of De Minimis Imports (akhandelwal8.github.io)

[9] FINAL_CBP FY 2023 Trade Fact Sheet CLEARED; U.S.: number of households 1960-2023 | Statista; The Value of De Minimis Imports | NBER

[10] FY2018-FY2021 De Minimis Statistics (cbp.gov)

[11] The Value of De Minimis Imports (akhandelwal8.github.io)

[12] GEA De Minimis Country information_4 November 2021.pdf (global-express.org)

[13] The Value of De Minimis Imports (akhandelwal8.github.io)

[14] The Value of De Minimis Imports | NBER

[15] U.S. Overdose Deaths Decrease in 2023, First Time Since 2018 (cdc.gov)

[16] https://www.cbp.gov/sites/default/files/assets/documents/2022-Oct/FY2018-2021_De%20Minimis%20Statistics%20update.pdf

[17] The Value of De Minimis Imports | NBER

[18] Border Patrol Salary Data for Agents and Other Professionals Within Customs and Border Protection (CBP) (borderpatroledu.org); Border Patrol Agent | CBP Careers; CBP SnapShot of Operations (FY2022 statistics); [18] Inadequate CBP Staffing at Ports Raises Security Concerns, Reardon Testifies – National Treasury Employees Union – NTEU

[19] New De Minimis One Pager (nftc.org)

[20] The Value of De Minimis Imports | NBER; Federal Register :: COBRA Fees to be Adjusted for Inflation in Fiscal Year 2024 CBP Dec. 23-08

[21] The Value of De Minimis Imports | NBER; New De Minimis One Pager (nftc.org)

[22] Text – S.1969 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): De Minimis Reciprocity Act of 2023 | Congress.gov | Library of Congress

[23] Text – H.R.4148 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): Import Security and Fairness Act | Congress.gov | Library of Congress

[24] Text – S.4082 – 118th Congress (2023–2024): Ensure Accountability in De Minimis Act of 2024 | Congress.gov | Library of Congress

[25] Text – H.R.7979 – 118th Congress (2023-2024): End China’s De Minimis Abuse Act | Congress.gov | Library of Congress; H.R. 7979, End China’s De Minimis Abuse Act | Congressional Budget Office (cbo.gov)

[26] FIGHTING for America Act One-pager (senate.gov)

[27] 19 U.S. Code § 2463 – Designation of eligible articles | U.S. Code | US Law | LII / Legal Information Institute (cornell.edu)