Research

March 28, 2019

DOL’s 2019 Proposed Overtime Pay Rule

Executive Summary

The Department of Labor (DOL) recently released a proposed regulation to update overtime pay protections under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA). The proposed rule, however, faces limitations similar to those in a previous regulation issued by the Obama Administration that never went into effect. A close look at the DOL’s new proposed rule reveals:

- Only 232,000 of the 1.3 million newly covered workers would regularly benefit from the rule;

- Across the low- and middle-wage workers impacted, the net average weekly pay increase would be only $4.54, while for most of those who regularly work overtime, the increase would be just $17.98;

- The majority of wage benefits would go to those who earn over $100,000 per year;

- The overall regulatory costs are roughly one-third of those imposed by the Obama-era regulation.

Overall, the DOL’s own analysis suggests that expanding overtime pay coverage is not an effective policy mechanism to raise wages.

Introduction

The Department of Labor (DOL) recently released the Trump Administration’s long-awaited proposed overtime pay rule. The DOL’s proposed rule would raise the minimum weekly pay threshold legally required to exempt low- and middle-income salaried workers from overtime pay from $455 per week ($23,660 annually) to $679 per week ($35,308 annually). The proposed rule comes after the DOL under the Obama Administration failed to implement a 2016 final rule to raise the salary threshold to $913 per week ($47,476 annually). A close examination reveals that, like the Obama Administration’s rule, the Trump Administration’s proposed regulation would provide little assistance to low- and middle-wage workers. For instance, while 1.3 million workers would become newly eligible for overtime pay, only 250,000 of those workers regularly work more than 40 hours per week and would benefit from the rule. Meanwhile, the rule will also impose over $1 billion in regulatory compliance costs over the next decade.

How the DOL Proposes to Adjust Overtime Pay Requirements

Under DOL regulations, there are three primary requirements to exempt a worker from overtime pay: the worker must be salaried (the salary basis test), the salary must meet a minimum level (the salary level test), and the worker’s duties must align with the definition of an executive, administrator, or professional (EAP) employee (the duties test). Under the Trump Administration’s proposed rule, the DOL would expand eligibility for overtime pay by adjusting the salary level test. In particular, it would raise the salary level requirement for both standard exemptions and highly compensated employees (HCE).[1] The DOL did not make any changes to the duties test.

The increase in the salary level required for standard exemptions is the primary way DOL is expanding overtime pay coverage. The DOL proposes to use the same methodology it employed in 2004—the last time it raised the salary threshold—and raise the weekly pay threshold to the 20th percentile of earnings for full-time salaried workers in the lowest-wage Census Region, currently the South. This means that the threshold would increase from $455 per week or $23,660 per year (set in 2004) to $679 per week or $35,308 per year.

The DOL is also adjusting the salary level required for the HCE exemption. The HCE exemption, introduced in 2004, imposes reduced duties requirements for employees who earn at least $100,000 per year. In the proposed regulation, the DOL would raise the HCE salary requirement to the 90th percentile of earnings of full-time salaried workers nationwide, which is $147,414 per year.

With this proposed regulation, the Trump Administration is also formally rescinding a more expansive Obama Administration overtime pay rule that was blocked by the courts. Finalized in 2016, the Obama Administration’s rule would have raised the salary level required for standard exemptions to the 40th percentile of earnings for full-time salaried workers in the lowest-wage Census Region (the South).[2] This would have resulted in a threshold of at least $913 per week or $47,476 per year. Additionally, the DOL would have started automatically updating the salary threshold requirement every three years to ensure it would remain fixed at the 40th percentile. Like the Trump Administration’s proposed rule, the Obama Administration’s final rule would have raised the HCE salary requirement to the 90th percentile of earnings of full-time salaried workers nationwide, which at the time was estimated to be $134,004 per year. Unlike the Trump Administration’s proposal, the HCE salary threshold would have risen every three years so it would remain fixed at the 90th percentile.

In August 2017, U.S. District Judge Amos Mazzant invalidated the Obama Administration’s regulation.[3] Judge Mazzant indicated that the DOL has the authority to adjust overtime pay rules by adjusting the salary threshold. He concluded, however, that President Obama’s overtime pay rule was unlawful because it raised the salary threshold by so much that it effectively made the duties requirements irrelevant.

The Obama Administration’s overtime pay rule was hailed by labor advocates as a “major victory for working people.” Likewise, supporters claimed Judge Mazzant’s decision was “deeply flawed” and the Trump Administration’s revised rule “a slap in the face to millions of workers.” In truth, however, analyses of the 2016 rule, including one by the DOL under President Obama, reveal that its impact on workers would have been limited. The DOL estimated that while the Obama Administration’s final rule would have expanded overtime pay protections to 4.2 million workers, average weekly earnings among those workers would have only grown by $5.48. Why? Only 825,000 of those workers regularly work more than 40 hours per week and would have started receiving overtime pay. Moreover, since employers would have cut back hours and base wages, those workers who regularly work overtime would have earned only an additional $20 per week. Meanwhile, the DOL estimated that the rule would have imposed $304.3 million in annual compliance costs.[4]

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) came to similar conclusions about the 2016 rule’s benefits to workers, but estimated that its compliance costs would have been even larger.[5] Specifically, the CBO estimates that compliance costs would have totaled over $1 billion per year, significantly larger than the DOL’s $304.3 million estimate. Although some workers would have experienced a small increase in wage earnings, the CBO estimates that the rule would have ultimately hurt families because companies would have passed these burdens onto consumers through higher prices. The CBO estimates that real family income would have declined by over $1.3 billion per year.[6]

Workers Impacted by the Proposed Rule

The DOL’s own analysis reveals that the Trump Administration’s proposed overtime pay rule similarly provides limited benefits to workers. Table 1 contains the number of EAP workers that the rule would impact, according to the DOL.

Table 1: Workers Impacted by Proposed Overtime Rule (thousands)

| Worker Category |

Total |

Impacted |

Regularly Work Overtime |

| Total EAP |

24,290 |

1,271 |

232 |

| Salary Level |

n/a |

1,070 |

152 |

| HCE Compensation Level |

n/a |

201 |

80 |

The DOL estimates that a small minority of the 24.3 million workers who currently qualify for an EAP overtime pay exemption would be impacted by the proposed rule. That is, the DOL estimates that 24.3 million workers currently qualify for either the standard exemption (earning over $455 per week and meeting duties requirements) or the HCE exemption (earning over $100,000 per year and meeting less stringent duties requirements). Just 1.1 million, however, earn between $455 and $679 per week and would be impacted by the standard salary level increase. Additionally, only 201,000 workers would be affected by the HCE compensation level increase. Thus 1.3 million workers could potentially gain overtime protections under the new rule.

The proposed rule’s impact is even more limited when considering its impact on worker earnings. Specifically, in order for the rule to meaningfully effect an individual worker’s earnings, that worker would have to regularly work over 40 hours per week. According to the DOL, however, only 232,000 of the 1.3 million workers affected by the rule regularly work overtime, 152,000 because of the standard salary level increase and 80,000 because the HCE compensation level increase.

Unfortunately, the impact of expanding overtime pay coverage is not as simple as giving 1.3 million workers a 50 percent raise for their overtime hours. In particular, the DOL recognizes that the cost of expanding overtime pay would result in lower base wages and fewer weekly hours for the 484,000 workers who either occasionally or regularly work overtime.

To evaluate the proposed overtime rule’s impact on wages and hours, the DOL breaks the 1.3 million newly covered workers into four main categories, shown in Table 2.

Table 2: The DOL’s Worker Types

| Category |

Total |

Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 |

Type 4 |

| Total | |||||

|

Workers (thousands) |

1,271 |

760 | 280 | 204 |

27 |

|

Percent |

100% |

60% | 22% | 16% |

2% |

| Standard Salary Level | |||||

|

Workers (thousands) |

1,070 |

649 | 270 | 127 |

24 |

|

Percent |

100% |

61% | 25% | 12% |

2% |

| HCE Compensation Level | |||||

|

Workers (thousands) |

201 |

111 | 10 | 77 |

3 |

|

Percent |

100% |

55% | 5% | 38% |

1% |

Type 1 workers never work overtime and thus would not be impacted by this rule change. The DOL estimates that there are 760,000 Type 1 workers, representing 60 percent of all newly covered workers. Type 2 workers are those who only occasionally work overtime and would be somewhat impacted by the rule. Type 3 workers are the 204,000 workers who regularly work overtime and will see the largest declines in wages and weekly hours. Finally, Type 4 workers also regularly work overtime, but earn a salary high enough that DOL expects their employers to increase their pay so they remain exempt. As a result, Type 4 worker wages would rise and their hours would not change. Only 27,000 workers fall under this category. Within each worker category, considerably more workers are affected by the standard salary level increase than by the HCE compensation level increase.

Table 3 illustrates how DOL expects the proposed overtime rule’s increases in the standard salary and HCE compensation levels would impact these workers’ base wages and hours.

Table 3: Overtime Pay Rule’s Impact on Wages and Hours

| Category |

Total |

Type 1 |

Type 2 | Type 3 |

Type 4 |

| Standard Salary Level | |||||

|

Wages |

0.0% |

0.0% | -0.3% | -4.3% |

6.3% |

|

Hours |

-0.2% |

0.0% | -0.1% | -0.9% |

0.0% |

| HCE Compensation Level | |||||

|

Wages |

-2.3% |

0.0% | -5.2% | -6.1% |

2.0% |

|

Hours |

-0.4% |

0.0% | -0.6% | -0.7% |

0.0% |

The DOL estimates that across all types of workers, the standard salary level increase does not impact average wages and lowers average weekly hours by 0.2 percent. Since the wage and hour effects would be concentrated on those who regularly work overtime, however, these figures hide the negative pay consequences for some workers. In particular, the DOL estimates that regular wages and hours for Type 3 workers—who regularly work overtime—would fall by 4.3 percent and 0.9 percent, respectively. Meanwhile, wages and hours of Type 2 workers—who occasionally work overtime—would fall by 0.3 percent and 0.1 percent. For Type 4 workers—whose pay would rise so they remain exempt—wages would rise 6.3 percent and their hours would be unaffected.

The DOL also estimates that among the small number of workers impacted by the HCE compensation level increase, wages and hours would, on average, decline by 2.3 percent and 0.4 percent, respectively. Again, this masks the negative impact on wages and hours among those who work overtime. For Type 3 workers, wages and hours would fall by 6.1 percent and 0.7 percent. For Type 2, they would decline by 5.2 percent and 0.6 percent.

After taking into account the changes in hours and wages, the DOL finds that the actual net benefit from earning overtime pay would be fairly small for a majority of those who would be impacted by the standard salary level increase. The average per worker net weekly earnings change is shown in Table 4.

Table 4: Overtime Pay Rule’s Net Impact on Weekly Pay

| Category |

Total |

Type 1 | Type 2 | Type 3 |

Type 4 |

| Standard Salary Level | |||||

|

Change |

$4.54 |

$0.00 | $5.47 | $17.98 |

$44.96 |

|

Change |

0.8% |

0.0% | 0.9% | 3.2% |

7.5% |

| HCE Compensation Level | |||||

|

Change |

$26.23 |

$0.00 | $59.70 | $58.68 |

$54.84 |

|

Change |

1.2% |

0.0% | 2.3% | 2.7% |

2.1% |

According to the DOL, across the 1.1 million workers who are newly covered due to the salary level increase, average weekly pay would only increase by $4.54. Average weekly earnings would not change for Type 1 workers. They would rise by $5.47 for Type 2 workers, $17.98 for Type 3 workers, and $44.96 for Type 4 workers. Thus, while weekly earnings would rise considerably among the few workers whose salaries would increase so they remain exempt (Type 4), they would only rise by under $20 for those who regularly work overtime and would now be eligible for overtime pay.

The proposed rule’s impact on weekly earnings would be more significant among the small number of well-compensated workers affected by the HCE compensation level increase. In particular, the DOL estimates that across those 201,000 workers, average weekly earnings would rise by $26.23. Again, pay among Type 1 workers would not change, but average weekly earnings would increase by over $50 for those who occasionally or regularly work overtime (Types 2, 3, and 4).

In total, the DOL estimates that for the 1.3 million workers who would be impacted by the proposed overtime pay rule, earnings would rise by $529.9 million in the first year. The vast majority of those workers would be impacted by the increase in the standard salary level. Across 1.1 million workers, wage earnings would rise by $252.5 million in the first year. However, the majority of the rule’s wage benefits would go to the few highly compensated workers impacted by the HCE compensation level increase. Earnings would rise by $274.3 million for the 201,000 workers impacted by that change. Thus, according to the DOL’s own calculations, the majority of the wage benefits would go to a handful of workers who, by their very definition, earn over $100,000 per year.

Compliance Costs

2016 Final Rule

- Total Costs (over 10 years): $2.9 billion

- Annualized Costs: $304.3 million

- Paperwork Burden: 2,507,338 hours

2016 Final Rule Under 2018 Analysis:

- Total Costs (over 10 years): $3.3 billion

- Annualized Costs: $338.6 million

2019 Proposed Rule:

- Total Costs (over 10 years): $1.1 billion

- Annualized Costs: $120.5 million

- Paperwork Burden: 2,583,414 hours

Increasing the threshold from the 2004 level will necessarily impose new costs. These costs, however, are substantially lower than those imposed by the 2016 rule – approximately one-third, in fact. Since fewer employees are now eligible for the overtime premium, fewer employers must now bear the costs of updating their payment practices. DOL estimates that this change saves employers $224 million on an annualized (in perpetuity at a 7 percent discount rate)[7] basis relative to the prior rule.

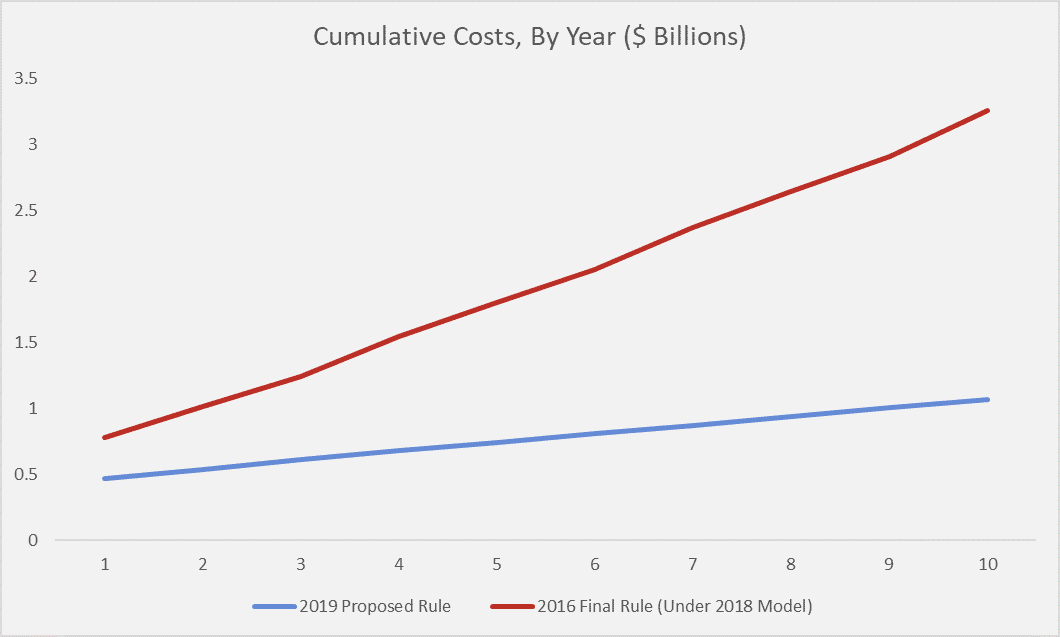

Beyond the overall, top-line cost figures, there is also a key difference in how these costs ramp up year-to-year. The following chart illustrates how the cumulative costs accrue during each year.

The 2016 rule’s steeper cost curve (and thus, widening gap) is a function of another key change in this proposed rule: the removal of the triennial threshold increases. Under the previous rule’s framework, the exemption threshold would modestly increase every three years automatically. As such, it would encompass a larger pool of employees and thus costs would increase at an increasingly higher rate over time. The current proposal does not include this mechanism. Therefore, costs will increase from year to year at a generally steady rate.

Deadweight Loss?

One aspect of the cost calculation that is curiously missing from the proposed rule’s regulatory analysis is the consideration of deadweight loss (DWL), or the value of the hours lost. There isn’t even a section explicitly explaining why it does not apply. The 2016 rule’s section on DWL describes how it applies to this regulation: “As the cost of labor rises due to the requirement to pay the overtime premium, the demand for overtime hours decreases, which results in fewer hours of overtime worked.” While the current proposal is a scaled back version of the 2016 rule, the effects on hours (see Table 3) are directionally similar, so one could expect some level of DWL.

As the 2016 rule details, the three variables needed to calculate deadweight loss are: “the increase in average hourly wages for affected EAP workers (holding hours constant); the decrease in average hours per worker; and the number of affected EAP workers. “

Since the subsets of employees affected by this regulation are one-half of Type 2 and Type 3, the analysis is confined to those groups. Additionally, the current proposal only includes relevant data for the first year, so this analysis is confined to that window currently. The following table lays out how each group could contribute to this DWL.

Table 5: DWL Breakdown for Year One

| Category |

Type 2 |

Type 3 |

| Standard Salary Level | ||

|

Workers (thousands) |

135 |

127 |

|

Change in Hours |

-.04 |

-0.5 |

|

Change in Hourly Pay w/ OT Premium |

-$.08 |

$.40 |

|

Annual DWL (millions) |

$.01 |

-$0.66 |

| HCE Compensation Level | ||

|

Workers (thousands) |

5 |

77 |

|

Change in Hours |

-0.3 |

-0.4 |

|

Change in Hourly Pay w/ OT Premium |

$1.51 |

$1.57 |

|

Annual DWL (millions) |

-$0.06 |

-$1.26 |

Total DWL (across all groups): $1.97 million

Paperwork Burdens

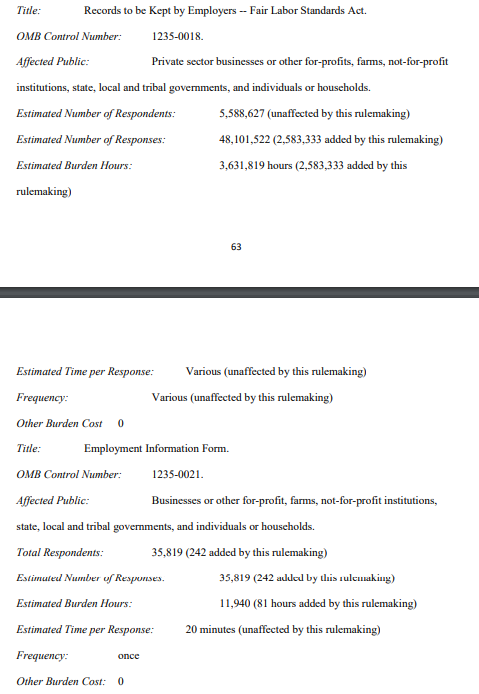

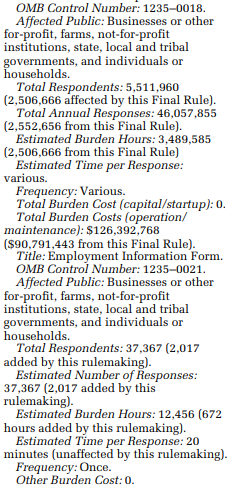

The section containing DOL’s analysis of the relevant paperwork burdens leaves further questions. While the current rule lowers the exemption threshold—and thus the potential pool of affected employees—the paperwork burden (across the two pertinent paperwork requirements) increases by 76,076 hours. Perhaps this is a result of more recent population data. Perhaps many of the otherwise-unaffected businesses still have to file certain forms, if only to prove to DOL that they are not affected. It is difficult to discern the rationale here as the proposed rule’s discussion of the paperwork requirements does not go into great detail on this. The other notable discrepancy (see below) is that the total costs for Control Number 1235-0018 under the old rule exceeded $126 million; there is no commensurate figure in the current proposal.

Conclusion

In light of the judicial decision on the Obama Administration’s 2016 overtime pay rule, and the Trump Administration’s propensity for taking a light regulatory posture, it is not surprising that the current version of the overtime rule is significantly pared back. Nevertheless, the new rule does make some substantial changes—as is to be expected when adjusting a regulatory program that has been stagnant since 2004. On the positive side, compliance costs for the new rule are billions less than they could have been under the Obama-era rule. On the negative side, many of the structural issues with regard to who benefits and how they benefit from this program largely remain.

[1] “Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees,” RIN 1235-AA20, Proposed Rule and Request for Comments, Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor, March 7, 2019, https://www.dol.gov/whd/overtime2019/.

[2] “Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional, Outside Sales and Computer Employees,” RIN 1235-AA11, Final Rule, 81 FR 32391, Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor, May 23, 2016, https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/05/23/2016-11754/defining-and-delimiting-the-exemptions-for-executive-administrative-professional-outside-sales-and.

[3] Daniel Wiessner, “U.S. judge strikes down Obama administration overtime pay rule,” Reuters, August 31, 2017, https://www.reuters.com/article/us-usa-overtime/u-s-judge-strikes-down-obama-administration-overtime-pay-rule-idUSKCN1BB2Y8.

[4] Ben Gitis & Dan Goldbeck, “Final Overtime Rule: Minimal Benefits and Major Costs,” American Action Forum, May 19, 2016, https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/final-overtime-rule-minimal-benefits-major-costs/.

[5] “The Economic Effects of Canceling Scheduled Changes to Overtime Regulations,” Congressional Budget Office, November 14, 2016, https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51925.

[6] Ben Gitis, “Comments to the DOL on Overtime Regulations,” Comments for the Record, American Action Forum, September 25, 2017, https://www.americanactionforum.org/comments-for-record/comments-dol-overtime-regulations/.

[7] The annualization calculation is what causes this figure to be different from the difference in annualized costs of the “2016 Final Rule Under 2018 Analysis” and “2019 Proposed Rule” figures.

September 25, 2017

Comments for the Record

Comments to the DOL on Overtime Regulations

Ben Gitis

The DOL must critically evaluate its methods for analyzing the effects of the overtime rule.