Research

October 21, 2024

The AAF Plan to Address the Nation’s Debt Challenge

Executive Summary

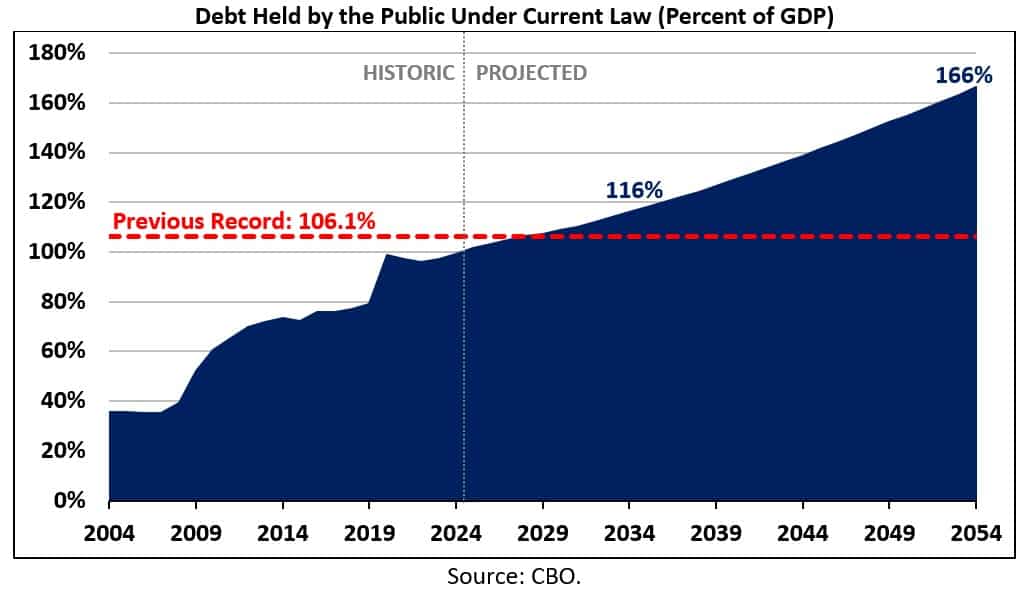

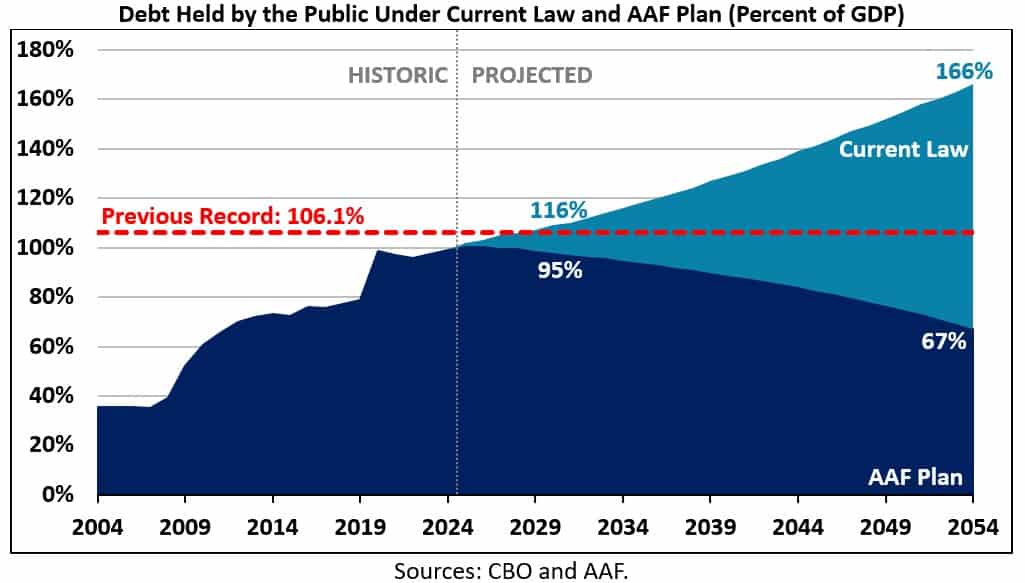

- The United States faces a litany of near-term budgetary and economic challenges and a fundamentally unsustainable long-term fiscal outlook, with the national debt projected to reach 166 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) by the end of fiscal year (FY) 2054 under current law.

- The American Action Forum (AAF) has developed a plan to foster faster economic growth and to promote a fiscal stance that reduces budget deficits and controls the national debt by emphasizing three core recommendations: entitlement reform, addressing global threats, and tax reform.

- Through a combination of revenue and spending changes, the AAF plan would save $7.1 trillion over the FY 2025–2034 budget window, enough to reduce debt to 95 percent of GDP by the end of FY 2034 and reduce the budget deficit to below 3 percent of GDP.

- Over the long term (FY 2025–2054), the plan would save $79.9 trillion and reduce debt to 67 percent of GDP by the end of FY 2054 while running a modest budget deficit of 0.4 percent of GDP.

Introduction

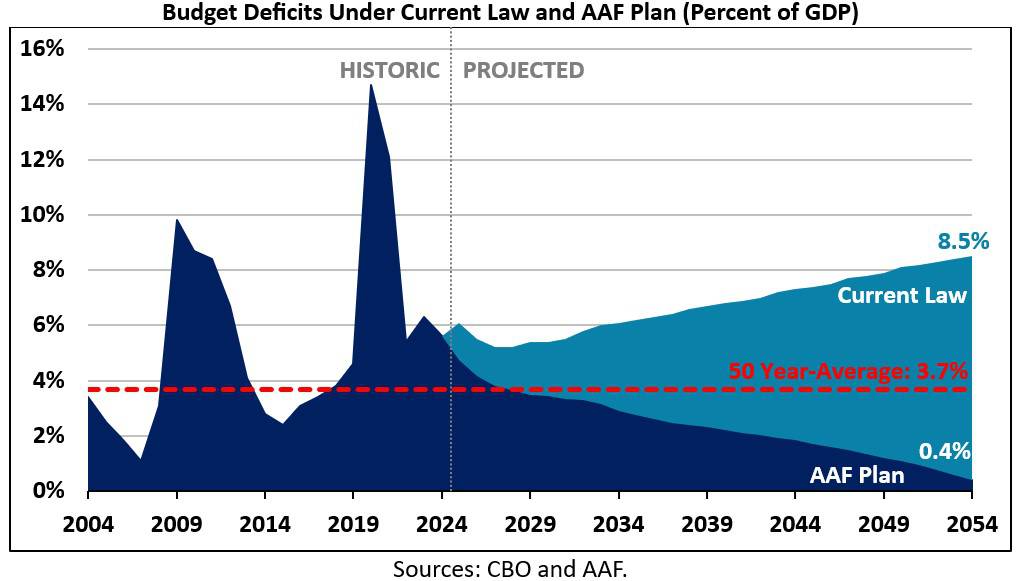

The nation’s two most pressing policy problems are the poor pace of economic growth and the unsustainable federal budget outlook. Under current law[1], the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the national debt will grow to 166 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) and the budget deficit will climb to 8.5 percent of GDP by the end of fiscal year (FY) 2054. Meanwhile, CBO expects annual economic growth to slow to 1.6 percent.

Federal fiscal policy is contributing to the slower pace of economic growth. It is widely understood that borrowing trillions of dollars when the economy is at full employment competes with private sector demands for capital. Reduced access to capital diminishes private-sector investment, thereby reducing growth in productivity and the standard of living.

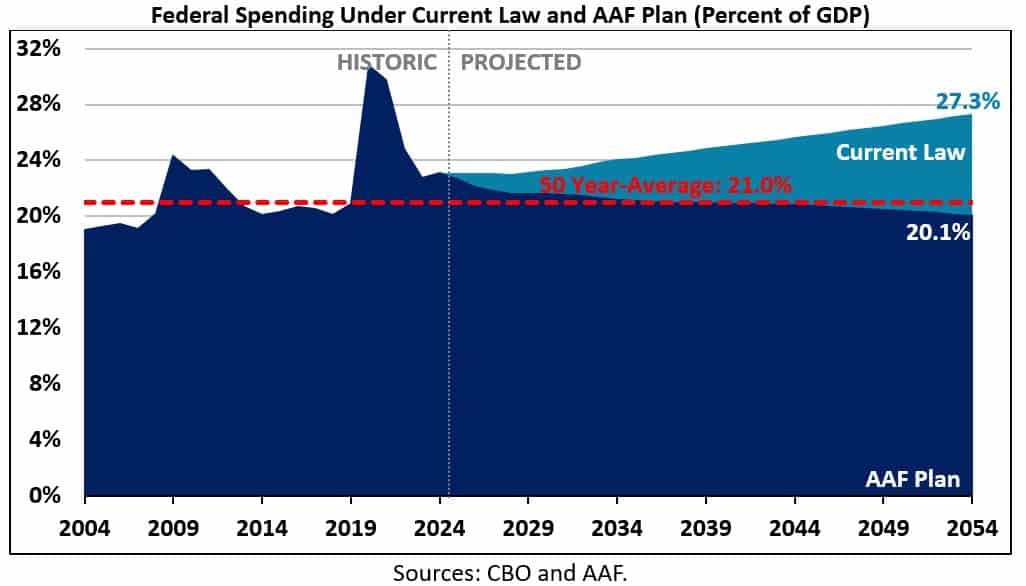

The way in which federal budget deficits are projected to evolve is especially anti-growth. Under current law, CBO projects that the deficit will rise from 6.1 percent of GDP in FY 2025 to 8.5 percent of GDP in 2054 – a 2.5 percentage point increase. Spending on Social Security will rise by 0.6 percentage points (from 5.3 to 5.9 percent of GDP) and Medicare spending will grow by 2.2 percentage points (from 3.2 to 5.4 percent of GDP). Thus, the continued growth of the nation’s two largest mandatory spending programs will outpace the projected growth in the budget deficit by 0.3 percentage points.

If resources are transferred from private-sector investment to federal subsidies to consumption, each dollar transferred reduces the growth in productivity, real wages, and the standard of living. This is true regardless of whether that transfer comes via taxes or deficit finance, but deficit finance is more likely to come at the expense of private investment. Past chronic federal deficits have already been a headwind to growth; the evolution of deficits over the next three decades is an even greater threat to growth.

To address the nation’s fiscal and economic challenges, the American Action Forum (AAF) developed a plan to foster faster economic growth and to promote a fiscal stance that reduces budget deficits and controls the national debt. The AAF plan provides guidance to address the following issue areas: reforms to Social Security and the nation’s major health care programs (Medicare, Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), and the Affordable Care Act (ACA) exchanges); comprehensive pro-growth tax reform; immigration reform; funding for national defense; and reforms to other areas of the federal budget. These reforms combine to stabilize debt as a share of the economy within a decade and put it on a downward path over the long term.

The AAF plan emphasizes three core recommendations: entitlement reform, addressing global threats, and tax reform. It recognizes that the U.S. faces several overlapping budgetary and economic challenges, and that time is quickly running out to stave off a potential debt crisis. Under successive presidential administrations and Congresses, the national debt has grown such that the cost of servicing it will exceed all spending on national defense this year. The nation’s accumulation of debt has mostly been the result of unique crises or the combination of multiple challenges. Policymakers’ failure to do the hard work of deficit reduction has put the U.S. at risk of being unable to meet future fiscal and economic challenges.

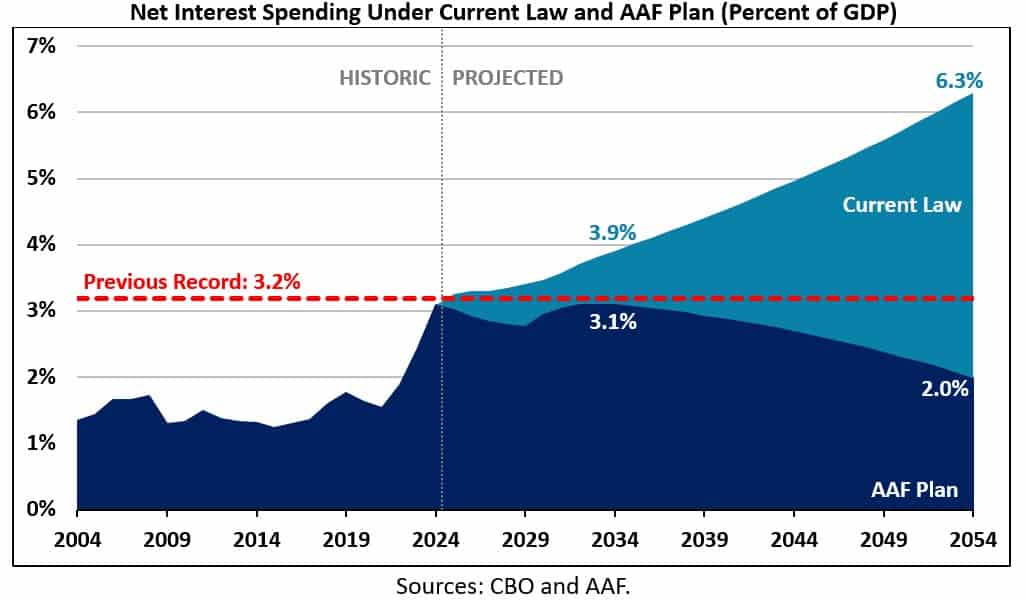

The Nation’s Fiscal and Economic Challenges

The AAF plan recognizes that the U.S. faces a litany of budgetary and economic challenges. Inflation is still above the Federal Reserve’s 2-percent target, with the Consumer Price Index (CPI) up 2.4 percent over the past year and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index up 2.2 percent. Meanwhile, the national debt is growing at an unsustainable rate. CBO’s March 2024 Long-Term Budget Outlook projects that federal debt held by the public will rise from 102 percent of GDP at the end of FY 2025 to a new record of 106.4 percent of GDP[2] by the end of 2028. It will grow further to 116 percent of GDP by the end of 2034 and continue to rise over the long term to 166 percent of GDP by the end of 2054. The annual budget deficit will total 6.1 percent of GDP by 2034 and 8.5 percent by 2054. Net interest costs will rise rapidly, reaching a record 3.4 percent of GDP[3] by 2025 and growing to 4.1 percent by 2034, and to 6.3 percent of GDP by 2054.

Excessive borrowing has contributed to these budgetary and economic challenges by exacerbating inflation, ballooning the national debt, and crowding out productive investments. Long-term deficit reduction can help the Federal Reserve tamp down inflation and reduce the magnitude of interest-rate hikes needed, thus reducing the likelihood of a recession. At the same time, deficit reduction can promote a stronger labor force, greater investment, and more economic growth. And most important, it can put the national debt on a more sustainable long-term path.

Selecting a Fiscal Goal

Any deficit reduction plan should focus on achieving fiscal sustainability. The AAF plan recognizes that there is no one right way to measure that sustainability, but that it is helpful to set a specific fiscal goal and then outline tax and spending changes to meet that goal. Choosing a fiscal goal requires choosing a metric to focus on (for example, deficits or debt), the specific target to aim for (for example, a debt-to-GDP ratio of 100 percent or full budget balance), and the time frame to achieve that goal (for example, 10 years or 30 years). The AAF plan aims to stabilize debt as a share of the economy within a decade and then put it on a downward path thereafter.

The AAF plan would achieve $7.1 trillion of deficit reduction over the FY 2025–2034 budget window, enough to reduce debt to 95 percent of GDP by the end of 2034 and reduce the budget deficit to below 3 percent of GDP. Over the long term (FY 2025–2054), the plan would save $79.9 trillion and reduce debt to 67 percent of GDP by the end of 2054 while running a modest budget deficit of 0.4 percent of GDP.

AAF’s Plan

AAF’s plan provides a framework to improve the federal budget outlook along with discussion of the types of policy changes that fit within the framework. As part of the Peterson Foundation’s Solutions Initiative, six other think tanks from across the ideological spectrum submitted their own plans (found here), which shows that there are many ways to improve the nation’s fiscal outlook. AAF’s plan includes savings from all major areas of the budget and federal tax code, with a focus on entitlement reform, addressing global threats, and tax reform.

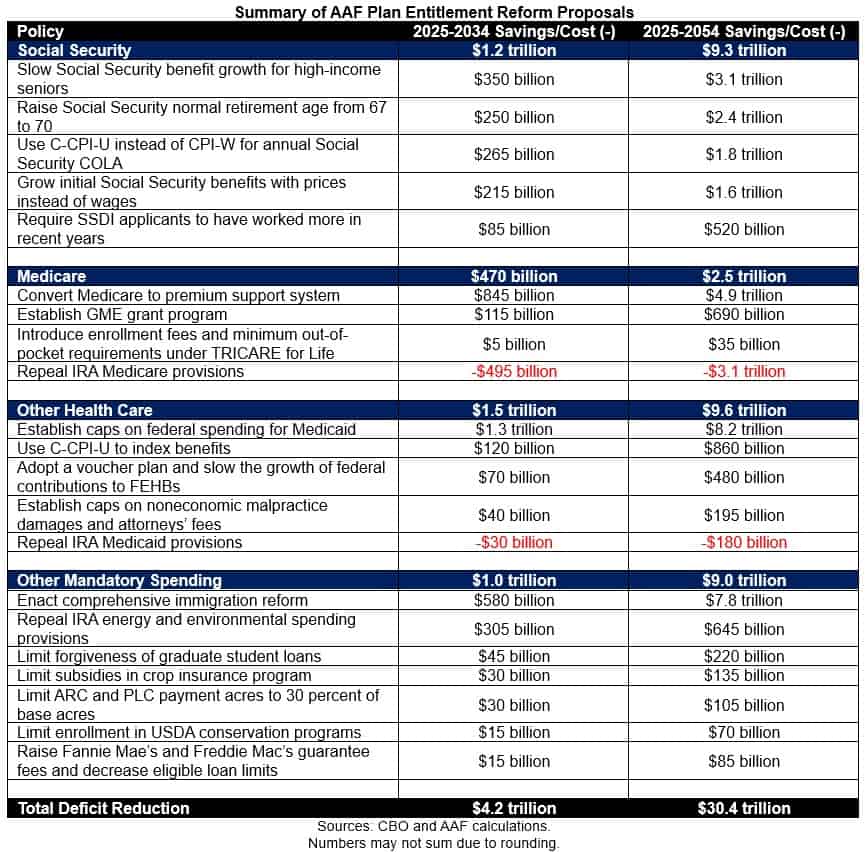

The AAF plan would save $7.1 trillion over the FY 2025–2034 budget window. This is the net effect of $4.2 trillion of savings from entitlement reform, $940 billion of new costs from addressing global threats, $1.9 trillion of new revenue from tax reform, $1.7 trillion of net interest savings, and $210 billion of macroeconomic feedback from the policy changes in the plan.

Over the long term (FY 2025-2054), the plan would reduce budget deficits by $79.9 trillion. These savings are the net effect of $30.4 trillion of deficit reduction from entitlement reform, $1.5 trillion of new costs from addressing global threats, $10.4 trillion of new revenue from tax reform, $32.7 trillion of net interest savings, and $7.8 trillion of macroeconomic feedback.

Recommendation #1: Entitlement Reform ($4.2 trillion/10 years; $30.4 trillion/30 years)

The AAF plan recognizes that the primary drivers of the nation’s future debt accumulation are its health and retirement programs, and any meaningful deficit-reduction package must substantially and materially reform them. Mandatory spending – including spending on Social Security and Medicare – has been growing as the population ages, health care costs grow, and policymakers create new entitlement programs and expand existing ones. In 1974, mandatory spending comprised 41 percent of the federal budget. Today, it comprises 61 percent of the budget and will grow to 62 percent by FY 2034. The last two major deficit-reduction packages – the Budget Control Act of 2011 and the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 – focused almost entirely on discretionary spending, which comprises only 26 percent of the budget. The fact that the nation’s fiscal outlook is still grim demonstrates that attention should be directed toward what’s really driving the nation’s rising debt burden: entitlement programs.

The AAF plan focuses on cost containment and slowing the growth of per-person health care spending, addressing Social Security’s long-term structural imbalance, and making reforms to other mandatory spending programs.

Social Security ($1.2 trillion/10 years; $9.3 trillion/30 years)

- Slow Social Security benefit growth for high-income seniors ($350 billion/10 years; $3.1 trillion/30 years). To calculate an individual’s Social Security benefits, the Social Security Administration (SSA) first looks at a beneficiary’s 35 highest-earning years to determine their average indexed monthly earnings (AIME). The beneficiary’s AIME is then run through a progressive replacement rate formula to determine their monthly benefit if they retire at Social Security’s normal retirement age of 67. The current benefit formula includes two “bend points” at which the marginal replacement rate for earnings changes. For 2024, the bend points are $1,174 and $7,078 and the marginal replacement rate equals 90 percent of the first $1,174 of AIME; 32 percent of AIME between $1,174 and $7,078; and 15 percent of AIME over $7,078. The AAF plan would replace the 90/32/15 percent factors with a 90/32/5 percent structure, which would make Social Security’s benefit formula more progressive by reducing benefits for high-income seniors.

- Raise Social Security normal retirement age from 67 to 70 ($250 billion/10 years; $2.4 trillion/30 years). Under current law, the normal retirement age for Social Security has gradually increased to age 67 for those born after 1960. The AAF plan would further increase the retirement age by two months per birth year for workers born between 1962 and 1978 so that the normal retirement age for all workers born in 1978 or later rises from 67 to 70. The earliest eligibility age for Social Security benefits would remain unchanged at age 62.

- Use C-CPI-U instead of CPI-W for annual Social Security COLA ($265 billion/10 years; $1.8 trillion/30 years). Under current law, all Social Security beneficiaries receive an annual cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) based on inflation, as measured by the Consumer Price Index for Urban Wage Earners and Clerical Workers (CPI-W). Many experts believe the CPI-W overstates cost-of-living changes. The AAF plan would switch to the Chained Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (C-CPI-U) for Social Security’s annual COLA. The C-CPI-U is considered a more accurate measure of inflation and grows an average of 0.25 percentage points more slowly per year than the traditional CPI.

- Grow initial Social Security benefits with prices instead of wages ($215 billion/10 years; $1.6 trillion/30 years). Under current law, an individual’s initial Social Security benefits are calculated based on their average lifetime earnings. The SSA calculates this average using a process known as wage indexing, which adjusts an individual’s prior earnings for changes in economywide wages. The AAF plan would move from wage indexing to progressive price indexing to calculate Social Security benefits for certain cohorts. For the highest income earners – that is, workers with 35 years of earnings at or above the taxable maximum of $168,600 – their Social Security benefits would grow with prices instead of wages.

- Require SSDI applicants to have worked more in recent years ($85 billion/10 years; $520 billion/30 years). To be eligible for benefits under the Social Security Disability Insurance (SSDI) program, most disabled workers must have worked five of the past 10 years. More specifically, workers over age 30 must have earned at least 20 quarters of coverage in the past decade. The AAF plan would require disabled workers over age 30 to have earned at least 16 quarters of coverage over the past six years, the equivalent of working four of the past six years. This policy change would apply to new SSDI applicants only.

Medicare ($470 billion/10 years; $2.5 trillion/30 years)

- Convert Medicare to a premium support system ($845 billion/10 years; $4.9 trillion/30 years). Under current law, the federal Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) program pays doctors, hospitals, and other health care providers separately for each service they provide based on a fee schedule that’s updated annually through federal regulation. FFS often incentivizes providers to provide unnecessary care, since payments are based on the quantity, rather than the quality, of care. The AAF plan would reform FFS and price it as a Medicare option with a market-based premium based on current FFS spending. The market-priced Medicare FFS option would then compete with Medicare Advantage. By introducing competition into the Medicare market, premiums may more accurately reflect costs and quality of care.

- Establish GME grant program ($115 billion/10 years; $690 billion/30 years). Hospitals with teaching programs can receive funding from Medicare to cover costs related to graduate medical education (GME). In addition, the federal government matches a portion of what state Medicaid programs pay for GME. The AAF plan would consolidate all federal mandatory spending for GME into a single grant program for teaching hospitals. Funding for the grant program would be indexed annually for the Consumer Price Index for All Urban Consumers (CPI-U) minus one percentage point.

- Introduce enrollment fees and minimum out-of-pocket requirements under TRICARE for Life ($5 billion/10 years; $35 billion/30 years). TRICARE for Life is a Medicare supplement for military retirees and their Medicare-eligible family members that covers most of their medical costs not covered by Medicare. The AAF plan would introduce annual enrollment fees in TRICARE for Life of $575 for individuals and $1,150 for families, indexed annually so they grow with average Medicare costs. The AAF plan would also impose minimum out-of-pocket requirements; in the first year, TRICARE for Life would not cover the first $850 of an enrollee’s cost-sharing payments under Medicare and would cover only half of the next $7,650 of payments. Each year, these dollar amounts would be indexed so they grow with average Medicare costs.

- Repeal IRA Medicare provisions (-$495 billion/10 years; -$3.1 trillion/30 years). The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) included several provisions to lower prescription drug costs by allowing the federal government to negotiate prices for drugs covered under Medicare Parts B and D; requiring drug companies to pay rebates to Medicare if drug prices rise faster than inflation; capping out-of-pocket spending for Medicare Part D enrollees; capping out-of-pocket costs for insulin at $35 per month for Medicare beneficiaries; and delaying implementation of the Trump Administration’s drug rebate rule, among other reforms. The AAF plan would repeal the IRA’s Medicare provisions beginning in 2025.

Other Health Care ($1.5 trillion/10 years; $9.6 trillion/30 years)

- Establish caps on federal spending for Medicaid ($1.3 trillion/10 years; $8.2 trillion/30 years). The federal government and state governments share the financing and administration of the Medicaid program, with the former providing most of the funding. Under current law, almost all federal Medicaid spending is open-ended, meaning if a state spends more due to increased enrollment or higher per-enrollee costs, larger federal payments automatically kick in. The AAF plan would establish per-enrollee spending caps on federal Medicaid spending. The caps levels would be indexed annually for the CPI-U plus one percentage point.

- Use C-CPI-U to index benefits ($120 billion/10 years; $860 billion/30 years). Under current law, some elements of Medicaid’s eligibility criteria, cost-sharing amounts, and disproportionate share hospital payments are indexed annually for inflation, as measured by the CPI-U. The AAF plan would switch to the C-CPI-U to index these benefits. The C-CPI-U is considered a more accurate measure of inflation and grows an average of 0.25 percentage points more slowly per year than the traditional CPI.

- Adopt a voucher plan and slow the growth of federal contributions to FEHBs ($70 billion/10 years; $480 billion/10 years). Under current law, the Federal Employee Health Benefits (FEHB) program provides health insurance to federal workers and their dependents and survivors. Policyholders generally pay 25 percent of the premium for low-cost plans and a higher percentage for high-cost plans and the federal government pays the rest of the premium. The AAF plan would, starting in 2025, replace the current premium-sharing structure with a voucher that is equal to the federal government’s average expected contributions to FEHB premiums in 2024, adjusted for the C-CPI-U.

- Establish caps on noneconomic malpractice damages and attorneys’ fees ($40 billion/10 years; $195 billion/30 years). Many states have their own individual caps on noneconomic malpractice damages (for example, the cap in Maryland is $800,000, $500,000 in Illinois, and $250,000 in California). Attorneys involved in medical malpractice litigation typically charge fees equal to one-third of total awards and waive the fee if no award is given. The AAF plan would establish a nationwide cap on noneconomic malpractice damages of $250,000 and cap attorneys’ fees.

- Repeal IRA Medicaid provisions (-$30 billion/10 years; -$180 billion/30 years). The IRA included several provisions to lower prescription drug costs, including allowing the federal government to negotiate prices for drugs and requiring drug companies to pay rebates to Medicare if drug prices rise faster than inflation. While the IRA’s prescription drug reforms primarily apply to Medicare, some provisions interact with Medicaid’s Drug Rebate Program. The IRA also included expanded access to vaccines for adults on Medicaid. The AAF plan would repeal the IRA’s Medicaid provisions beginning in 2025.

Other Mandatory Spending ($1.0 trillion/10 years; $9.0 trillion/30 years)

- Enact comprehensive immigration reform ($580 billion/10 years; $7.8 trillion/30 years). The AAF plan includes a fundamental immigration reform. On net, this reform would reduce budget deficits and have a positive effect on economic growth. Conversely, enforcing existing immigration policies would increase budget deficits and have a negative effect on economic growth, requiring an increase in federal spending of roughly $500 billion to deport those in the U.S. illegally and to prevent future illegal entry into the country.

- Repeal IRA energy and environmental spending ($305 billion/10 years; $645 billion/30 years). The IRA committed hundreds of billions of dollars to environmental spending and tax credits. On the spending side, this included investments in low-carbon materials and buildings; funding for biomass, carbon removal, and forest management; energy innovation; offshore wind and oil and gas systems; energy efficiency; and agriculture. The AAF plan would repeal the IRA’s energy and environmental spending provisions.

- Limit forgiveness of graduate student loans ($45 billion/10 years; $220 billion/30 years). Under current law, the federal government can forgive undergraduate and graduate student loans under certain circumstances. The AAF plan would limit forgiveness of student loans for graduate borrowers by increasing the percentage of discretionary income that graduate borrowers on income-driven repayment plans pay on their loans to 15 percent and raising the repayment period until loan forgiveness to 25 years.

- Limit subsidies in crop insurance program ($30 billion/10 years; $135 billion/30 years). The crop insurance program protects farmers from low market prices and losses from natural disasters. Farmers can select the amount and type of insurance and the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) sets premiums equal to expected payments for farmers for crop losses. On average, the federal government subsidizes 60 percent of premiums. Private insurance companies sell and service the policies purchased through the crop insurance program and the federal government reimburses them for administrative expenses. The AAF plan would reduce the subsidy rate to 40 percent and limit federal reimbursement to crop insurance companies for administrative expenses to an average of 9.25 percent of estimated premiums and target the annual return on investment for those companies to 12 percent.

- Limit ARC and PLC payment acres to 30 percent of base acres ($30 billion/10 years; $105 billion/30 years). The Agriculture Risk Coverage (ARC) and Price Loss Coverage (PLC) programs provide financial support to producers of certain commodities. Only commodity producers who have established base acres with the USDA may participate in the ARC and PLC programs and eligibility for the programs is based on their planting histories. Payment acres range from 65–85 percent under the ARC program and 85 percent under the PLC program. The AAF plan would limit payment acres under the ARC program to 23–30 percent of base acres and 30 percent of base acres under the PLC program.

- Limit enrollment in USDA conservation programs ($15 billion/10 years; $70 billion/30 years). The USDA offers a Conservation Stewardship Program that allows owners of working farms and ranches to enter into contracts with the USDA to maintain existing, and to undertake new, conservation measures in exchange for annual payments and technical assistance. The USDA also offers a Conservation Reserve Program that allows owners of working farms and ranches to enter into contracts with the USDA to stop production on specified tracts of land in exchange for annual payments and grants to establish conservation practices on that land. The AAF plan would prohibit new enrollment in the Conservation Stewardship Program, as well as new enrollment and reenrollment in the general enrollment portion of the Conservation Reserve Program.

- Raise Fannie Mae’s and Freddie Mac’s guarantee fees and decrease eligible loan limits ($15 billion/10 years; $85 billion/30 years). Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) established to help maintain a stable supply of financing for residential mortgages. These GSEs purchase mortgages from lenders and pool those mortgages together to create mortgage-backed securities that are sold to investors and guaranteed (for a fee) against losses from defaults. In 2024, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac can purchase mortgages up to $1,149,825 in areas with high housing costs and $766,550 in other areas. The AAF plan would increase the average guarantee that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac assess on loans by five basis points and reduce the maximum mortgage amount in all areas.

Recommendation #2: Address Global Threats (-$940 billion/10 years; -$1.5 trillion/30 years)

The U.S. faces an increasingly complex and diverse set of national security threats. Successive national security strategies have identified Russia and China as posing stark and unique threats, in addition to the persistent challenges from rogue nations such as North Korea and Iran, as well as transnational terrorism. These threats are far from abstractions. Russia has provoked a land war in Europe, China continues to signal aggressive intentions toward Taiwan, Iran and the U.S. have come as close to open warfare since the 1980s, while North Korea continues to develop its strategic nuclear forces. Contemporaneously, U.S. forces are engaged throughout the world in a counter-terror mission against prolific and evolving threats. Fundamentally, the U.S. must acknowledge these realities and prepare accordingly. The AAF plan would increase total discretionary spending levels relative to what is projected under current law, though the plan does include some policy proposals that would save money.

Defense Discretionary Spending (-$960 billion/10 years; -$1.6 trillion/30 years)

- Increase defense funding (-$980 billion/10 years; -$1.7 trillion/30 years). The AAF plan would provide additional defense discretionary funding to meet the growing challenges of the global security environment. Over the first decade (FY 2025–2034), defense outlays would rise commensurate with additional appropriations consistent with those authorized in the National Security Act. In the latter two decades (FY 2035–2054), the additional defense funding would phase down to more modest additions.

- Modify TRICARE enrollment fees and cost-sharing for working-age military retirees ($15 billion/10 years; $85 billion/30 years). Under current law, active-duty military personnel and their families, retired military personnel and their families, and members of other uniformed services and their families are eligible to receive health care through the Department of Defense’s TRICARE program. The AAF plan would increase TRICARE’s enrollment fees, deductibles, and copayments for working-age military retirees. Specifically, beneficiaries with individual coverage would pay $650 annually to enroll in TRICARE Prime; the annual cost for family enrollment would be $1,300. Beneficiaries with individual coverage would pay $485 annually to enroll in TRICARE Select; the annual cost for family enrollment would be $970 and the annual deductible for TRICARE Select would be $300 for individuals and $600 for families. Finally, the schedule of copayments and medical treatments under TRICARE Prime and Select would be the same for all retirees in the first year and then rise in subsequent years with the growth of per-person health care spending.

Nondefense Discretionary Spending ($20 billion/10 years; $85 billion/30 years)

- Repeal Davis Bacon Act ($20 billion/10 years; $85 billion/30 years). Under the Davis Bacon Act, all workers on federally funded or assisted construction projects whose contracts exceed $2,000 are to be paid the prevailing wage in the area where the project is located. The AAF plan would repeal the Davis Bacon Act, which would lower the federal government’s construction costs.

Recommendation #3: Tax Reform ($1.9 trillion/10 years; $10.4 trillion/30 years)

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) marked the first substantial reform to the U.S. federal tax code in 30 years, but the task is far from finished. The most conspicuous challenge and opportunity in this task is reflected in the sunset of substantially all the law’s individual income tax reforms, as well as some of its business provisions. A durable tax reform should build on the best elements of the TCJA and reform those that could be improved. The tax reform proposals in the AAF plan are described below.

Individual Income Taxes ($165 billion/10 years; -$2.0 trillion/30 years)

- Return individual income tax rates and brackets to pre-TCJA levels, indexed annually for the Chained CPI ($285 billion). The TCJA reduced statutory individual income tax rates at almost all levels of taxable income and shifted the thresholds for several income tax brackets. Under pre-TCJA law, the tax brackets were indexed annually for inflation, though the TCJA changed the inflation measure used for indexing from the CPI-U to the C-CPI-U. The AAF plan would restore the pre-TCJA rate structure starting in tax year 2025 but would maintain the use of the C-CPI-U for the indexing of brackets.

- Make TCJA standard deduction structure permanent (-$1.4 trillion/10 years; -$6.4 trillion/30 years). The TCJA nearly doubled the standard deduction to $12,000 for single filers, $24,000 for married couples filing jointly, and $18,000 for heads of households in tax year 2018 (under pre-TCJA law, the amounts would have been $6,500, $13,000, and $9,550, respectively). Under pre-TCJA law, the deduction was indexed annually for inflation, though the TCJA changed the inflation measure used for indexing from the CPI-U to the C-CPI-U. The standard deduction amounts for tax year 2024 are $14,600 for single filers, $29,200 for married couples filing jointly, and $21,900 for heads of households. The TCJA’s larger standard deduction is scheduled to sunset at the end of 2025. The AAF plan would make permanent the TCJA’s structure of the standard deduction.

- Make TCJA repeal of personal exemptions permanent ($2.3 trillion/10 years; $10.5 trillion/30 years). Under pre-TCJA law, taxpayers could claim personal exemptions for themselves, their spouses, and any dependents equal to $4,050. Each exemption would reduce their taxable income by such amounts. The policy phased out for single filers earning more than $261,500 and for couples earning more than $313,800. The TCJA temporarily repealed the use of personal exemptions through the end of 2025. The AAF plan would make permanent the TCJA’s repeal of personal exemptions.

- Repeal individual AMT (-$795 billion/10 years; -$4.8 trillion/30 years). The TCJA maintained the individual Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) but raised the exemption and income levels at which the AMT exemption phases out. The individual AMT is a separate federal tax structure that requires some taxpayers to calculate their federal income tax liability twice – once under ordinary income tax rules and again under the AMT – and pay whichever amount is highest. Under pre-TCJA law, the AMT exemption amounts were $55,400 for single filers and $86,200 for married couples filing jointly in tax year 2018, indexed annually for the CPI-U. The amounts phased out at taxable income above $123,100 for single filers and at $164,100 for couples, indexed annually for the CPI-U. For tax year 2018, the TCJA increased the exemption amounts to $70,300 for single filers and to $109,400 for couples, indexed annually for the C-CPI-U. The amounts phased out at taxable income above $500,000 for single filers and at $1 million for couples, indexed annually for the C-CPI-U. For tax year 2024, the AMT exemption amounts are $85,700 for singles and $133,300 for couples, phasing out at taxable income of $609,350 and $1,218,700, respectively. The TCJA’s individual AMT changes are scheduled to sunset at the end of 2025. The AAF plan would permanently repeal the individual AMT.

- Repeal estate, gift, and generation-skipping transfer taxes for descendants (-$450 billion/10 years; -$2.6 trillion/30 years). The federal estate tax applies to the transfer of property at death. For tax year 2024, the estate tax applies to estates over $13.6 million for single filers and $27.2 million for married couples filing jointly, levied at a top rate of 40 percent. The federal gift tax applies to the transfer of property by a living individual without payment or a valuable exchange in return. For tax year 2024, the gift tax applies to gifts over $18,000 from single persons and to gifts over $36,000 from couples, imposed at a top rate of 40 percent. The federal generation-skipping transfer (GST) tax applies to the transfer of property or assets to individuals that are more than one generation below the transferor (for example, from a grandparent to grandchild). For tax year 2024, the GST tax exemption amounts are $13.6 million for single filers and $27.2 million for couples, levied at a top rate of 40 percent. The AAF plan would permanently repeal the estate, gift, and GST taxes.

- Replace stepped-up basis with carryover basis ($180 billion/10 years; $930 billion/30 years). Under current law, investors are generally taxed on their capital gains – that is, the increased value of their stocks and other assets – at the time of sale. When a person dies and passes their asset on to an heir, the “basis” (the assumed purchase price) of the asset is “stepped-up” to reflect its current value, and when the heir sells the asset, they only pay taxes on the gains accrued while the asset was in their possession. This creates a substantial loophole that allows some capital gains to escape taxation altogether. To close this loophole, the AAF plan would replace the stepped-up basis with a carryover basis, which would require inheritors of assets to pay capital gains taxes based on the purchase price of the asset at the time of sale.

- Replace pass-through deduction with 25-percent rate cap on business income*. The TCJA created a new deduction for pass-through business owners under Internal Revenue Code Section 199A. The Section 199A deduction allows eligible individuals, businesses, trusts, and estates with pass-through business income to deduct up to 20 percent of their qualified business income from their taxable ordinary income. The Section 199A deduction is scheduled to sunset at the end of 2025. The AAF plan would replace the deduction with a 25-percent rate cap on the profits of pass-through business owners that are taxed under the individual income tax and enforce the 70/30 rule (which is based on the premise that economic output is 70 percent returns to labor and 30 percent returns to capital, and that ratio should apply to the income of pass-through business owners), consistent with the proposal in the House GOP’s “A Better Way for Tax Reform” blueprint for pro-growth, comprehensive tax reform.

Payroll Taxes ($360 billion/10 years; $775 billion/30 years)

- Increase Social Security taxable maximum to cover 90 percent of earnings ($940 billion/10 years; $4.4 trillion/30 years). Currently, wages up to $168,600 are subject to the 12.4 percent Social Security payroll tax. The AAF plan would increase the taxable share of earnings subject to the payroll tax to 90 percent in calendar year 2025. In subsequent years, the taxable maximum would grow at the same rate as average wages.

- Repeal additional Medicare surtax and Net Investment Income Tax (-$580 billion/10 years; -$3.6 trillion/30 years). Enacted as part of the ACA, the additional Medicare surtax imposes a 0.9-percent tax on earned income above $200,000 for single filers and $250,000 for married couples filing jointly. The Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) imposes a 3.8 percent tax on investment income above $200,000 for single filers and $250,000 for couples. The AAF plan would permanently repeal the additional Medicare surtax and the NIIT.

Corporate Income Taxes ($790 billion/10 years; $2.7 trillion/30 years)

- Impose destination-based cash-flow tax ($1.1 trillion/10 years; $4.2 trillion/30 years). The AAF plan would eliminate the newly imposed international tax regime and replace it with a destination-based cash-flow tax that’s consistent with the proposal in the House GOP’s “A Better Way for Tax Reform” blueprint for pro-growth, comprehensive tax reform. Businesses would be able to immediately fully expense their capital investments instead of depreciating them over several years. At the same time, businesses would no longer be able to deduct their net interest expenses from their taxable income and foreign profits would no longer be subject to domestic taxation. In addition, the corporate income tax would be destination-based, meaning that the U.S. income tax would be border-adjustable.

- Repeal Corporate AMT (-$245 billion/10 years; -$1.1 trillion/30 years). The IRA created a 15-percent corporate AMT that’s imposed on corporations with average annual adjusted book income over $1 billion for three consecutive years. Like the rules governing the individual AMT, corporations must calculate their federal income tax liability twice – once under the statutory corporate income tax rate and then under the corporate AMT – and pay whichever amount is highest. The AAF plan would permanently repeal the corporate AMT.

- Repeal corporate stock buybacks excise tax (-$90 billion/10 years; -$390 billion/30 years). The IRA created a 1 percent excise tax on corporate stock buybacks, net of new issuances of stock, during a taxable year. Stock contributed to retirement accounts, pensions, and employee-stock ownership plans are exempt from the tax. The AAF plan would permanently repeal the corporate stock buybacks tax.

Tax Expenditures (-$210 billion/10 years; $2.9 trillion/30 years)

- Phase out mortgage interest deduction ($455 billion/10 years; $5.9 trillion/30 years). The mortgage interest deduction is an itemized deduction for interest paid on home mortgages. The TCJA temporarily reduced the allowable deduction from $1 million to $750,000 through the end of 2025. The AAF plan would phase out the mortgage interest deduction for existing mortgages over 10 years.

- Replace charitable contributions deduction with new tax credit for charitable contributions ($240 billion/10 years; $925 billion/30 years). The TCJA temporarily increased the percentage of charitable contributions made in cash that can be deducted from a taxpayer’s taxable income each year from 50 percent to 60 percent through the end of 2025. The AAF plan would replace the charitable deduction with a new tax credit equal to 15 percent of all charitable contributions above $500, indexed annually for the C-CPI-U.

- Limit ACA PTCs to 300 percent of poverty ($55 billion/10 years; $225 billion/30 years). The ACA created refundable premium tax credits (PTC) to help eligible individuals and families cover the cost of premiums for health insurance purchased through the health insurance marketplace. The American Rescue Plan made the PTCs more generous for 2021 and 2022 and the IRA extended the enhanced subsidies through the end of 2025. Currently, there is no maximum income limit for the PTCs. The AAF plan would limit eligibility for the subsidies to incomes at or below 300 percent of the federal poverty level.

- Provide tax credit for first-time homebuyers (-$960 billion/10 years; -$4.2 trillion/30 years). The AAF plan would create a refundable tax credit for first-time homebuyers equal to 15 percent of the value of the purchased home, claimed in five equal increments in each of the first five years of ownership.

Other Taxes ($835 billion/10 years; $6.0 trillion/30 years)

- Impose $25 per metric ton carbon tax, indexed 5 percent plus inflation ($835 billion/10 years; $6.0 trillion/30 years). The AAF plan would levy a $25-per-metric-ton tax on energy-related emissions of carbon dioxide in the U.S. (including emissions from electricity generation, manufacturing, and transportation), and some other greenhouse gas emissions from large U.S. manufacturing facilities. The rate of taxation would increase at an annual rate of 5 percent plus the inflation rate from the prior year.

Net Interest Savings ($1.7 trillion/10 years; $32.7 trillion/30 years)

By reducing the federal debt burden, the AAF plan would generate roughly $1.7 trillion of net interest savings for the federal government over the FY 2025-2034 budget window and $32.7 trillion over 30 years (FY 2025-2054). Reductions in debt service under the AAF plan would grow over time, helping to slow the growth of net interest payments relative to what is projected under current law. By 2034, net interest would be $280 billion lower than what is projected under current law; that reduction would rise to $1.3 trillion by 2044 and to $3.5 trillion by 2054. And instead of growing to a record 3.3 percent of GDP by next year, net interest as a share of the economy would never eclipse the prior record of 3.2 percent of GDP observed in 1991.

Macroeconomic Feedback ($210 billion/10 years; $7.8 trillion/30 years)

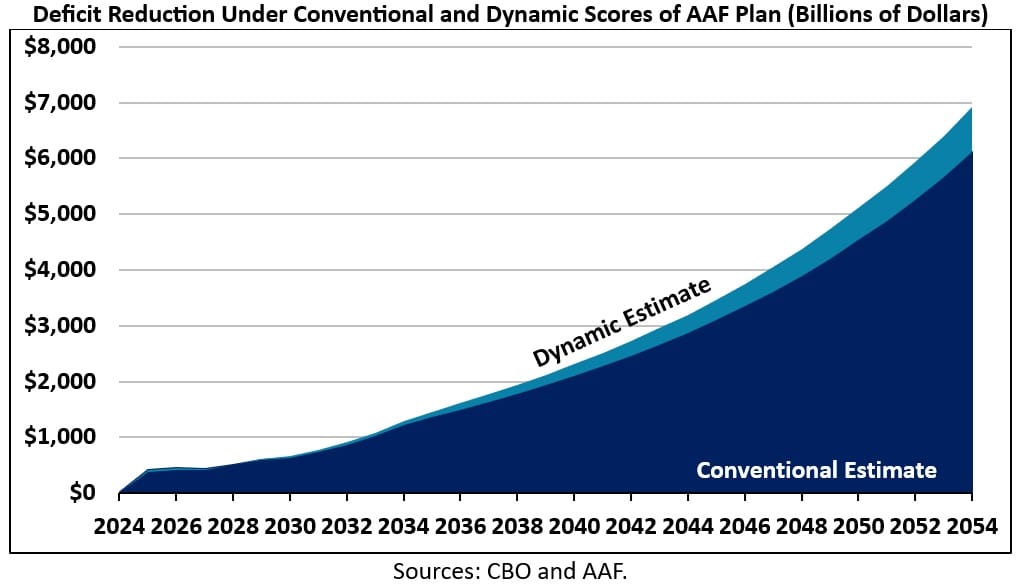

Under a conventional estimate, the AAF plan would generate $6.9 trillion in deficit reduction over the FY 2025-2034 budget window and $72.1 trillion over 30 years (FY 2025-2054). This conventional estimate of the AAF plan fails to address how the revenue and spending changes in the plan would affect output, incomes, employment, and other macroeconomic factors. A dynamic estimate incorporates the macroeconomic effects of policy changes on the federal budget.

Under a dynamic estimate, the AAF plan would generate $210 billion of macroeconomic feedback over the FY 2025-2034 budget window and $7.8 trillion over 30 years. As a result, the plan would generate $7.1 trillion of deficit reduction over a decade and $79.9 trillion over three decades.

The Fiscal Impact of the AAF Plan

The AAF plan would lower budget deficits and debt, help to fight inflation, restore long-term solvency to the Social Security and Medicare programs, strengthen economic and income growth, and promote fairness and efficiency within the federal government.

Under the AAF plan, federal debt held by the public would fall from 102 percent of GDP at the end of FY 2025 to 95 percent of GDP by the end of 2034. Debt would continue to decline thereafter, ultimately falling to 67 percent of GDP by the end of 2054. For comparison, under current law, debt is projected to grow to 116 percent of GDP by the end of 2034 and rise further to 166 percent of GDP by the end of 2054. In other words, the AAF plan would eliminate over half of the projected debt accumulation over the next three decades. At the same time, debt-to-GDP would never eclipse the prior record set just after World War II in 1946.

Annual budget deficits would be lower under the AAF plan than under current law. The deficit in FY 2034 would total 2.9 percent of GDP, which is 3.2 percentage points lower than the current-law projection of 6.1 percent of GDP. In 2054, the AAF plan would run a modest budget deficit of 0.4 percent of GDP, which is 8.1 percentage points lower than the 8.5 percent of GDP current-law projection.

Federal spending would be lower under the AAF plan than under current law. Spending in FY 2034 would total 21.3 percent of GDP, which is 2.8 percentage points lower than the current-law projection of 24.1 percent of GDP. Spending would fall further to 20.1 percent of GDP in 2054, which is 7.2 percentage points lower than the 27.3 percent of GDP current-law projection.

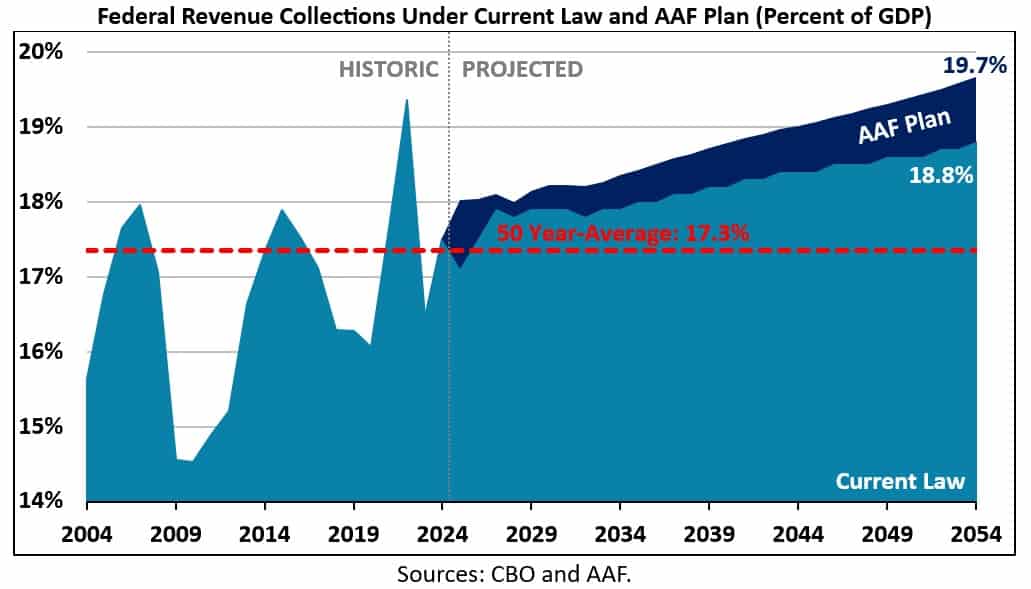

Federal revenue collections, meanwhile, would be higher under the AAF plan than under current law. Revenue in FY 2034 would total 18.4 percent of GDP, which is 0.5 percentage points higher than the current-law projection of 17.9 percent of GDP. Revenue collections would grow further to 19.7 percent of GDP in 2054, which is 0.9 percentage points higher than the 18.8 percent of GDP current-law projection.

Conclusion

The United States faces a litany of near-term budgetary and economic challenges and a fundamentally unsustainable long-term fiscal outlook. The AAF plan includes sweeping policy changes to both the revenue and spending sides of the federal budget and would achieve the fiscal goal of roughly stabilizing debt-to-GDP within a decade and putting it on a downward path thereafter. In fact, the plan would eliminate more than half of the projected debt accumulation over the next three decades. With these changes, spending in FY 2054 would be more than seven percentage points of GDP lower than what is projected under current law and revenue would be nearly one full percentage point of GDP higher. In sum, this plan would drastically improve the United States’ dangerous current fiscal outlook, but policymakers must act soon as the time remaining to address the looming crisis in a sober way is disappearing fast.

Endnotes

[1] The AAF plan was scored against CBO’s March 2024 Long-Term Budget Outlook. CBO has since released An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2024 to 2034 with slightly different budget projections over the 2024 to 2034 budget window. To present an apples-to-apples comparison of budget projections under current law and the AAF plan, any mentions of “current law” in this analysis refer to CBO’s March 2024 Long-Term Budget Outlook.

[2] The record for debt as a share of GDP is 106.1 percent in FY 1946.

[3] The record for interest as a share of GDP is 3.2 percent in FY 1991.