Research

March 31, 2025

Trump’s Reciprocal Tariffs: Potential Scenarios and Cost Estimates

Executive Summary

- On April 2, the Trump Administration’s “reciprocal tariffs” – import duties that are designed to match the tariff and non-tariff barriers of other countries – are set to go into effect.

- As of March 31, it is unclear how the administration will calculate reciprocal tariffs and to what extent these tariff rates will factor in non-tariff barriers or value-added taxes; two potential approaches include a country-by-country rate or separate rates on a product-by-product level.

- Assuming the administration utilizes a country-by-country approach with a weighted average tariff rate applying to harmonized tariff schedule sectors, reciprocal tariffs will cost U.S. consumers and firms between $26.3–34.5 billion in the first year; factoring in value-added taxes would increase costs by an additional $214.4 billion.

Introduction

The Trump Administration’s “reciprocal tariffs” – import duties that are designed to match the tariff and non-tariff barriers of other countries – are set to go into effect on April 2, a date the president and his trade team have dubbed “Liberation Day.” The groundwork for these tariffs was outlined in the White House’s February 13 memorandum, which detailed the president’s “Fair and Reciprocal Plan” for U.S. trade policy. As of March 31, it is unclear how the administration will calculate reciprocal tariffs and to what extent these tariff rates will factor in non-tariff barriers or value-added taxes, with numerous methods and ideas being considered every week since the announcement. Two potential approaches include a broader country-by-country rate or a more specific rate at the product-by-product level.

Given the uncertainty surrounding the implementation of these tariffs, cost estimates are difficult to come by as it is unclear how non-tariff barriers will be priced, which countries might reach a deal before the tariffs are implemented, to what extent any deals might reduce or eliminate tariffs, and how fine-tuned the tariff rates will be. Assuming the administration utilizes a country-by-country approach with a weighted average tariff rate applying to harmonized tariff schedule sectors, this research estimates that reciprocal tariffs will cost U.S. consumers and businesses between $26.3–34.5 billion in the first year. This estimate factors in noncompliance and other offsets and will likely end up being a low-end estimate as it does not account for the pricing of non-tariff barriers. If the administration were to incorporate value-added taxes in the reciprocal tariff rates on trade partners, total costs would balloon by an additional $214.4 billion in the first year of implementation.

What Are Reciprocal Tariffs?

A tariff is a tax placed on imports entering a country for business or consumer purposes, usually taking the form of a flat fee or a percentage of the product’s value. This protectionist tool is used to defend domestic industries from foreign competitors by raising the cost of imported products for consumers, who end up paying the tariff or purchasing alternative domestic products. Other rationales for tariffs include national security concerns, raising revenue, retaliating against other countries, or using them as a bargaining chip in negotiations.

Figure 1: Reciprocal Tariff Visual Representation

A reciprocal tariff is one that matches the tariff of another country. For example, assume the United States has a 2-percent tariff on a trade partner’s imports while the trade partner has a 10-percent tariff on U.S. imports. A U.S. reciprocal tariff would mean raising the 2-percent tariff to 10 percent to match the trade partner’s tariff rate, ensuring “reciprocity.” The United States may remove its reciprocal tariffs if the trade partner decides, in response, to lower its tariff rate on U.S. products. This represents one positive of trade policies that seek reciprocity as they may encourage U.S. trade partners to lower trade barriers, resulting in a mutually beneficial opening of markets, thus expanding market access for U.S. companies and lowering costs for U.S. consumers. The downside of this trade policy is that it also leads the United States to match the protectionist policies of other countries, which ultimately reduces the buying power and number of choices for U.S. consumers – with no guarantee of success that countries will relent and lower their tariff and non-tariff trade barriers.

Instituting reciprocal tariffs is not as simple as one country matching the tariff of another country. The United States imports thousands of different goods from more than 175 countries, with numerous separate tariff rates, fees, quotas, and other barriers that depend on the country and product. Perfect reciprocity would require the United States to match every tariff rate for every product from every country, an administrative nightmare that would mean creating a new trade regime with potentially more than 2 million different tariff rates. This raises the question of how the Trump Administration will realistically implement reciprocal tariffs.

How Might Reciprocal Tariffs Be Implemented?

There are a few different approaches to implementing reciprocal tariffs, with the two main methods being country-level reciprocity and product-level reciprocity. The level of reciprocity heavily influences how complex of an administrative system is needed as well as how close U.S. tariff rates are to those of other countries.

Country-by-country: Imposing reciprocal tariffs on a country-by-country basis would involve placing a single tariff on each country based on that country’s average tariff rate (weighted by trade value). For example, the weighted average tariff rate of Brazil on U.S. products is a little less than 6 percent. Using the country-level approach, the United States would raise its tariffs on Brazil to 6 percent no matter the product. This would significantly simplify keeping track of tariffs but at the cost of being less precise in differentiating among imports. This broader approach makes a difference; for example, the Brazilian tariff on U.S. lumber is as high as 19 percent but only 0.05 percent on U.S. fuels, meaning a flat 6-percent tariff is not completely reciprocal.

Product-by-product: Imposing reciprocal tariffs on a product-by-product basis would involve placing separate tariff rates for each imported product based on its harmonized tariff schedule (HTS) code. For example, cotton products, which fall under the two-digit HTS code 52, face completely different tariff rates than aluminum products, which fall under the two-digit HTS code 72. Breaking it down to the most granular 10-digit HTS level, woven fabrics under 85 percent cotton by weight (HTS 5212250000) may face a separate tariff rate than cotton sewing thread (HTS 5204200000) despite both products falling under the same two-digit HTS code category. A perfect reciprocity scenario would be to create a tariff regime at the 10-digit HTS level, although this would require more than 2 million separate tariff rates for all potential imports from all trade partners. Although the two-digit level is less precise, it is more realistic to implement and is more accurate than instituting an average tariff rate as in the country-by-country approach.

Another approach considered by the Trump Administration is the creation of a three-tiered tariff system that sorts trade partners based on their level of tariffs and other trade barriers. Although easier to manage, this would be even broader and less fine-tuned than country-by-country reciprocal tariffs, likely sparking greater backlash from trade partners grouped in with countries that have more protectionist policies.

What Might Reciprocal Tariffs Cost?

Speculation surrounding how reciprocal tariffs will be calculated and implemented has changed week-to-week with every White House press conference or speech by a member of the Trump trade team. In recent weeks, however, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick confirmed that the administration would likely be using “one number” for each country, meaning reciprocal tariffs will likely reflect the weighted average tariffs imposed on the United States. The single rate for each country may also attempt to factor in non-tariff barriers and value added taxes (VATs), although it is unclear how the administration will go about this. The scenarios below only look at reciprocity in terms of tariffs and utilize the country-by-country approach, with weighted average tariff rates applied at the section HTS level (the broadest level). In scenario one, U.S. tariffs increase or decrease to match trade partners, while in scenario two, U.S. tariffs are only ratcheted up to match trade partners.

Scenario One: Increase and Decrease Tariff Rates

If the administration moves tariff rates either higher or lower to match trade partners, this research estimates that reciprocal tariffs will incur a net tax liability of $26.3 billion. This number includes both tax increases from tariff rate increases and tax decreases from the more limited tariff rate decreases.

The U.S. tariff rates used are from the year 2021, meaning many of the recent tariff changes in 2025 have not been factored in. Removing China, Mexico, and Canada from the data to account for recent targeted tariffs, the total cost falls to $15.3 billion.

Scenario Two: Only Increase Tariff Rates

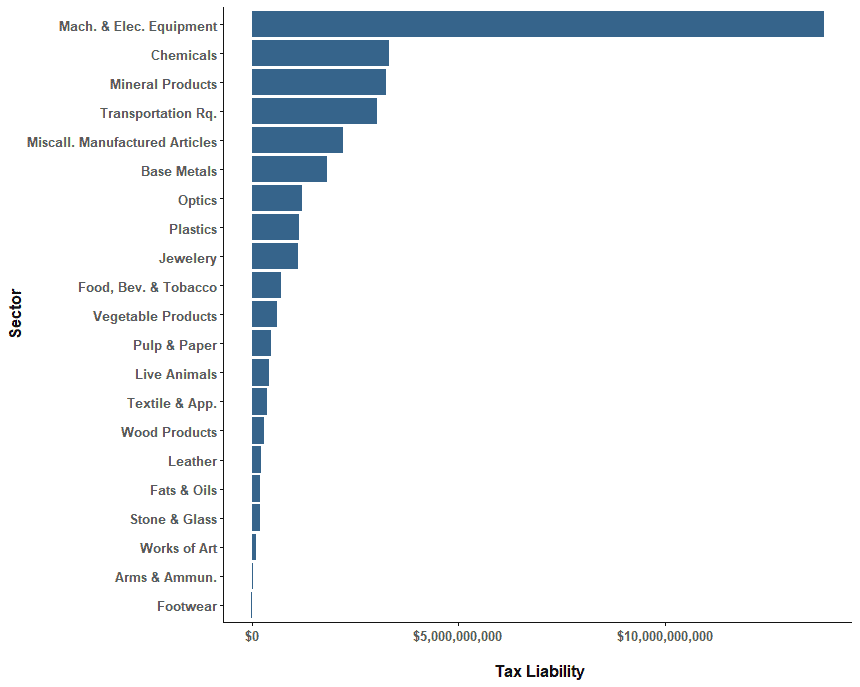

The more likely avenue the administration will take is to raise tariff rates on trade partners with higher tariffs. The administration has displayed little willingness to allow tariff exemptions or remove trade barriers, meaning it is unlikely that U.S. tariffs will be lowered to match those of other countries. This research estimates that such a plan would result in $34.5 billion in total tax liabilities for U.S. consumers and businesses. Removing China, Mexico, and Canada from the data leaves total costs at $21.8 billion. Figure 2 displays the cost increase by sector. See Figure 4 in the appendix, which displays the percentage increases in weighted average tariff rates by sector.

Figure 2: Cost Increase by Sector of Reciprocal Tariffs

Source: Feodora Teti’s Global Tariff Database (v_beta1-2024-12) from Teti (2024), U.S. International Trade Commission DataWeb, World Bank WITS Database.

Factoring in Non-tariff Barriers

As outlined in the White House reciprocal trade memo, the administration plans to account for non-tariff barriers when implementing reciprocal tariffs. A non-tariff barrier refers to bans, restrictions, lengthy approval processes, fees, or other policies that restrict foreign trade and protect domestic firms. These barriers are often complex, opaque, and costly for firms to navigate, which makes them more difficult to quantify than tariffs. Some barriers, such as restrictions on U.S. corn grown with glyphosate, can be easily priced, while others, such as unequal permitting processes, are nearly impossible to prove, let alone price. Any cost estimate for non-tariff barriers, including from within the administration, will inevitably be arbitrary and subject to error.

Previously, President Trump had specifically called out value-added taxes (VATs) as a non-tariff barrier that could be included in a reciprocal tariff calculation. As American Action Forum President Douglas Holtz-Eakin notes, VATs, which are similar to a sales tax, are applied to domestic and imported goods equally, which means that they provide no inherent advantage to domestic industries. A VAT is just an economically efficient sales tax and not akin to a tariff, although it does provide a far easier measure to estimate costs than non-tariff barriers.

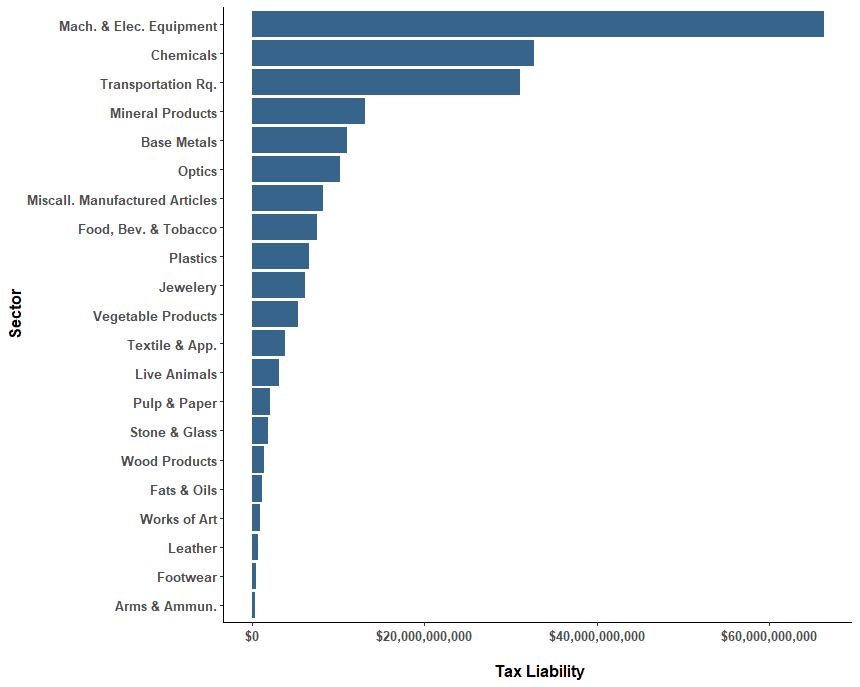

Were the administration to incorporate VATs, this research estimates that “reciprocal” tariffs on trade partners equal to their VAT rate would cost U.S. firms and consumers $214.4 billion more in additional annual costs, at least in the first year. This number represents the impact before supply chains shift and consumer behavior changes, which would create additional ripple effects throughout the economy. The reciprocal VAT impact is more than six times higher than that of direct reciprocal tariffs. See Figure 3 for the cost increase by sector of reciprocal VATs and Figure 5 in the appendix for the percentage increase in the weighted average tariff by sector.

U.S. imports from the European Union would be particularly hurt by a “reciprocal” VAT. This analysis finds that U.S. firms would pay an additional $58.6 billion on European goods alone, which is nearly double the cost of a reciprocal tariff regime on all imports.

Figure 3: Cost Increase by Sector of Reciprocal VATs

Source: Feodora Teti’s Global Tariff Database (v_beta1-2024-12) from Teti (2024), U.S. International Trade Commission DataWeb, PWC report.

Conclusion

The specific method the Trump Administration will use to implement and enforce reciprocal tariffs is unclear, as is whether the tariffs will prove permanent. No matter which scenario is used to calculate these tariffs or whether non-tariff barriers are heavily factored in, costs will increase for U.S. consumers and businesses, at least in the short term. If this policy results in other countries lowering trade barriers and opening markets for U.S. firms, that may offer certain positive outcomes. If, however, there are no negotiations, there will be negative economic consequences. Such cost estimates of reciprocal tariffs range from $26.3 billion to more than $200 billion if non-tariff barriers are factored in.

Appendix and Methodology:

This research used U.S. import tariff data from Feodora Teti’s Global Tariff Database (v_beta1-2024-12) from Teti (2024), which was accurate to the HTS Section level. These tariff rates were weighted by product category at a lower HTS level. Meanwhile, this research found average trade partner tariff rates from the World Bank’s WITS database and average VAT rates from a PWC report. The 2024 trade volume data came from the U.S. International Trade Commission’s DataWeb database. This research used the average tariff rates instead of itemized rates because the administration has stated it will base reciprocal tariff rates on averages for countries, not itemized rates.

This research also transformed the tariff rate changes to account for income and payroll tax offsets, tariff evasion rates (85 percent), and the tax inclusive rate.

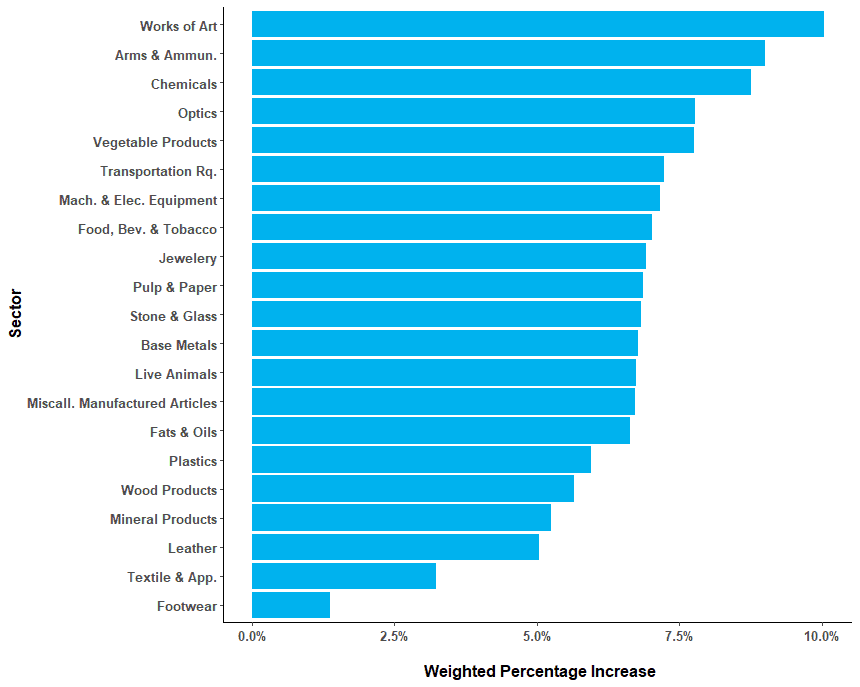

Figure 4: Percentage Increase in Weighted Average Tariff Rate From Reciprocal Tariffs

Source: Feodora Teti’s Global Tariff Database (v_beta1-2024-12) from Teti (2024), U.S. International Trade Commission DataWeb, World Bank WITS Database.

Figure 5: Percentage Increase in Weighted Average Tariff Rate From Reciprocal VATs

Source: Feodora Teti’s Global Tariff Database (v_beta1-2024-12) from Teti (2024), U.S. International Trade Commission DataWeb, PWC report.