Research

January 30, 2025

Where are the NIH’s Funding Priorities?

Executive Summary

- The National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the largest funder of biomedical research globally, investing more than $45 billion annually, and its choices in funding dispersal dictate the state of research both domestically and internationally.

- Researchers have voiced concerns that NIH’s funding priorities fail to reflect contemporary disease burdens, do not account for geographic and institutional disparities in grant allocation, and often unduly favor late-career scientists, and , in response, have proposed a range of reforms intended to foster greater efficiency and more multi-faceted, novel research.

- As the new Congress and administration may consider reforms to NIH, this insight provides a brief overview of the agency’s background and structure, and highlights areas of potential improvement in its funding strategies, allocation processes, and NIH’s overall research impact.

Introduction

The National Institutes of Health (NIH), a subagency within the Department of Health and Human Services, has long been the backbone of U.S. health research, distributing more than 80 percent of the world’s public biomedical research funding while supporting nearly 99.7 percent of all approved drugs in the country. The agency has come under greater scrutiny from policymakers, however, in part due to the brighter spotlight on public health from the COVID-19 pandemic, and in part due to researchers’ methodological concerns regarding its internal processes and research outcomes.

NIH is designed to address the nation’s evolving health needs using a maximally efficient allocation process, but macro-level studies of its funding decisions have found misalignments with changing disease profiles, scientific innovation, and equitable access. Various studies demonstrate these misalignments and have downstream effects for public health outcomes. In response, researchers within and outside of the NIH have proposed several reforms to align NIH investments with the most pressing health issues and to support greater diversity and efficiency in funding such investments. These reforms include the promotion of new productivity metrics in funding decisions and increasing variety among funded institutions, states, and experience levels to foster greater efficiency and more multi-faceted, novel research.

As the new Congress and administration may consider reforms to NIH, this insight provides a brief overview of the agency’s background and structure, and highlights areas of potential improvement in its funding strategies, allocation processes, and NIH’s overall research impact.

NIH’s Scale and Significance

NIH serves as the cornerstone of the United States’ biomedical research enterprise, operating as a subagency within the Department of Health and Human Services. NIH is led by the Office of the Director, which sets priorities for and coordinates among the 27 institutes and centers. In the fiscal year (FY) 2024 enacted appropriations, NIH received a total program budget of more than $47.3 billion, reflecting a decrease of $368 million (0.8 percent) from the previous fiscal year – the first reduction since FY2013. When including the Advanced Research Projects Agency for Health (ARPA-H), the combined NIH and ARPA-H program levels experienced a 0.7-percent decline.

Distributing more than 80 percent of the world’s biomedical research funding, NIH contributed to the foundational research for 386 out of 387 FDA-approved products between 2010 and 2019, representing 99.7 percent of approvals.

Source: National Institutes of Health

The vast majority of NIH funding comes from annual discretionary appropriations, supplemented by smaller sources such as mandatory budget authorities for specific research areas. Between FY1999 and FY2003, NIH funding increased annually by 14–16 percent as part of a doubling initiative. After this period, inflation-adjusted funding declined until FY2015, when Congress began gradual increases, bringing the FY2023 budget to approximately $46.2 billion.

Almost all of NIH’s funding is allocated in the annual Departments of Labor, Health and Human Services, and Education, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act. In addition, NIH receives smaller amounts of funding from the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act, as well as a mandatory budget authority for type 1 diabetes research.

How NIH Allocates Funding

While NIH’s scope is vast, its approach to funding is highly structured. Funding decisions are made through a competitive grants process, which involves multiple steps designed to ensure that the most promising research proposals receive financial backing.

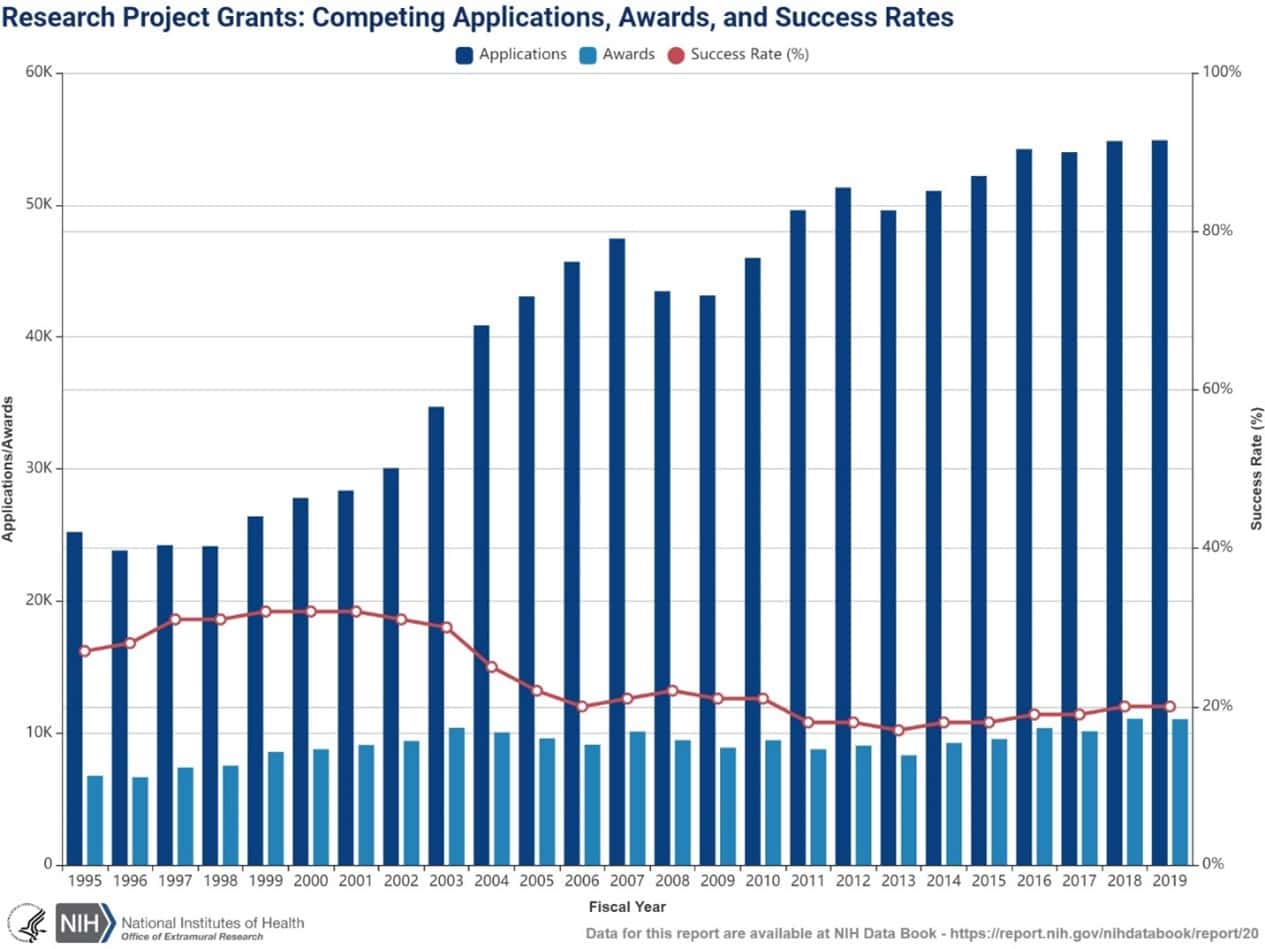

NIH funding decisions are determined by a rigorous, multidimensional review process. First, grant applications undergo a peer review, where experts from two separate organizations evaluate proposals based on their scientific merit, potential impact, and feasibility. After this initial review, applications are ranked, and only the top tier receives funding. The success rate for research project grants has hovered around 20 percent, as illustrated in the figure below. Applications have steadily increased while awards have remained relatively flat, leading to intense competition for NIH funding. This hypercompetitive environment for grant applications has led to a historically lower success rate for research project grants.

Source: NIH Office of Extramural Research

The heightened competition for NIH funding tends to favor conservative, short-term projects with predictable outcomes. This trend may discourage innovation by incentivizing young post-doctoral researchers to focus on familiar academic areas rather than exploring novel ideas. Translational research – studies directly linked to medical practice – has been prioritized for its clear connection to practical outcomes. While this emphasis has significant benefits, many researchers claim it often comes at the expense of broader, fundamental biological research, potentially limiting groundbreaking scientific discoveries.

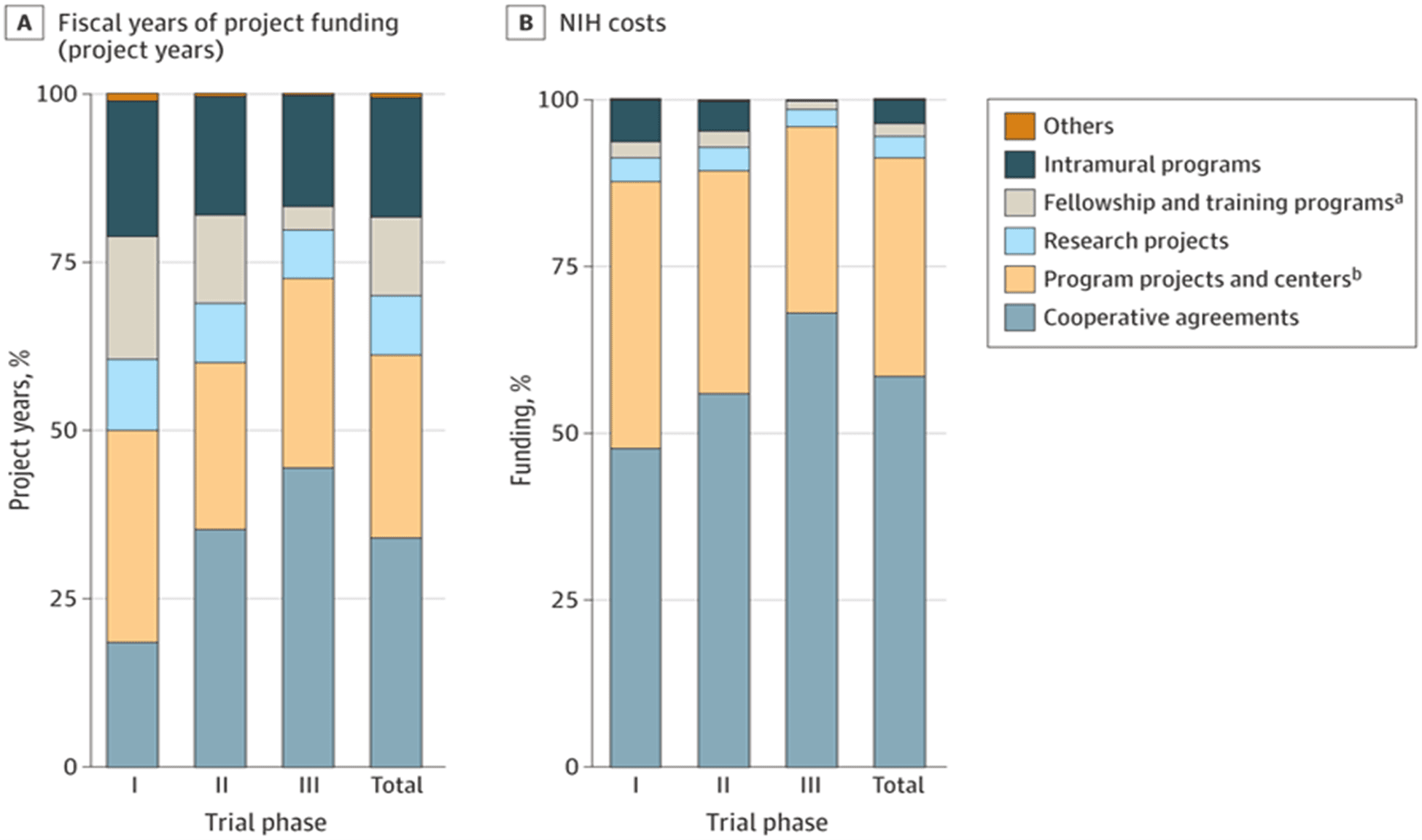

One of NIH’s most important functions is funding early clinical research, which takes the form of trials and basic scientific research and serves as the foundation for later pharmaceutical drugs and innovation. This funding for early-phase clinical trials is mostly through the U-series (cooperative agreements). These U-series grants foster collaborations between NIH and researchers on larger, more complex project areas. The P-series (program project/center grant) support collaborative efforts and multi-institution research projects. These are typically reserved for large research centers or institutions. The R-series (research grant), such as the widely known R01 grant, support individual research projects without the need for direct NIH supervision.

Source: JAMA Health Forum

Analyzing NIH grant types provides crucial context for who is receiving funding, how much funding they are receiving, and the potential drivers of inefficiencies in the system. Since the vast majority of early-phase funding comes from the U, P, and R series, these three grants are of central focus to biomedical researchers and of this analysis.

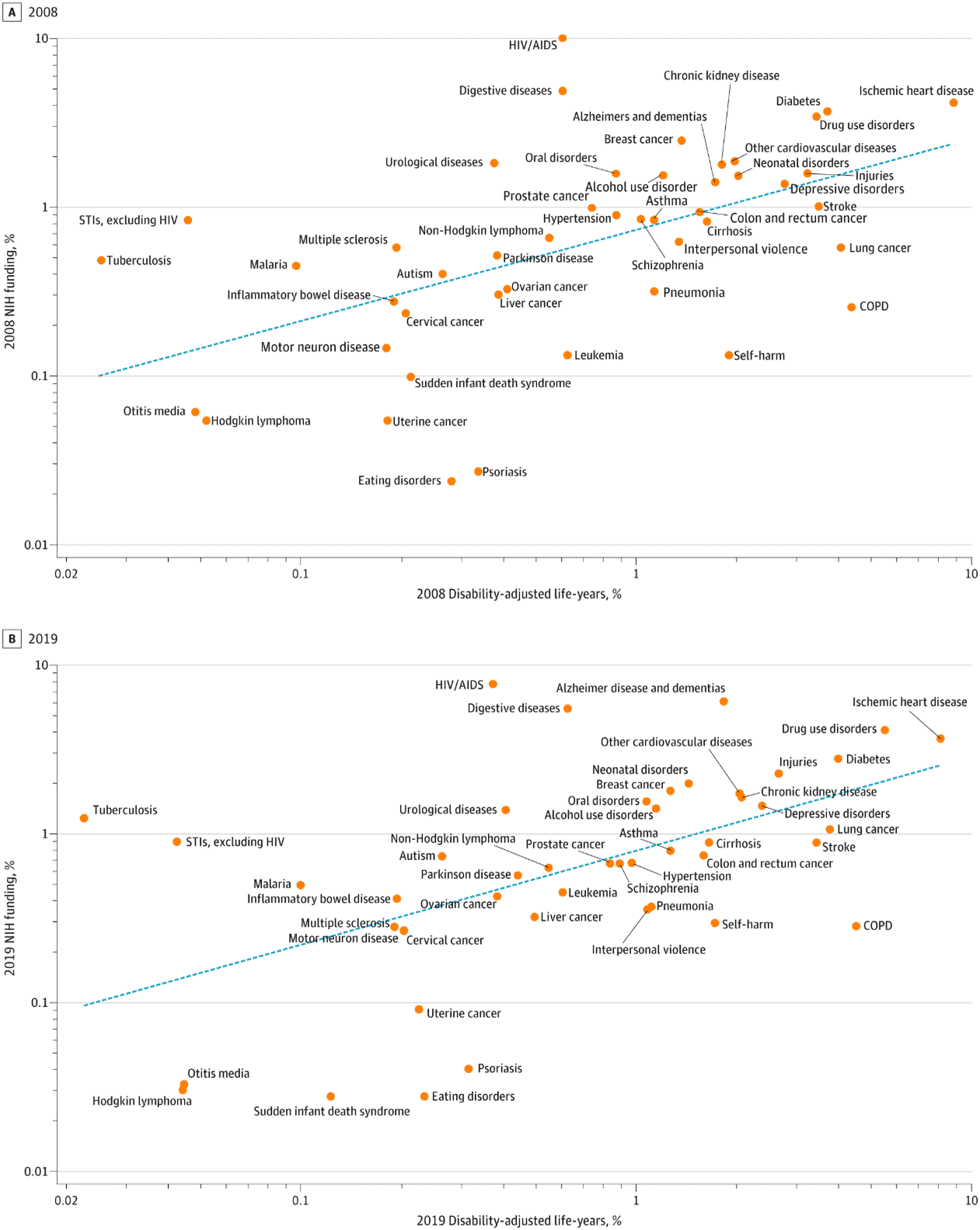

NIH Does Achieve Core Functions

A core function of the NIH is accurately assessing funding priorities to match the U.S. disease burden. To do so, the NIH makes a concerted effort to fund sub-agencies and projects based on the proportional impact of a health problem on the population. Studies show that NIH meets these general requirements. NIH funding is broadly correlated with the prevalence and effects of disease in the United States. As the burden of a disease, measured in Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) increases, there is a corresponding trend of increased funding for that disease. This follows, as the more prevalent a disease, the greater the amount of expected public funding. Yet although there is a positive linear trend between prevalence and level of funding for a cohort of diseases, examining individual diseases shows certain areas are vastly overfunded or underfunded.

Source: Ballreich et al., Allocation of National Institutes of Health Funding by Disease

According to temporal reviews of NIH funding, NIH spending for most diseases seemed to be based primarily on the level of NIH spending more than 10 years earlier, regardless of changes in the burden of disease over time. So, while the line of best fit does meet the core function of aligning with disease burden there are various areas clearly overfunded or underfunded; for example, in pediatric research. The following section discusses the potential causes behind this misalignment.

Weaknesses of the Current Model

Criticism of NIH funding decisions and allocations spans multiple dimensions. Researchers have identified several systemic weaknesses that they contend collectively hinder innovation and funding diversity. These include institutional and geographic imbalances, biases favoring certain awardees, overconcentration of funding leading to diminishing returns, and misalignments between funding priorities and current disease burdens.

Institutional and Geographic Biases

NIH has faced criticism for disproportionately allocating funding to specific geographic regions. Data shows that institutions and universities in states with historically well-established research infrastructure, such as Massachusetts and California, receive disproportionately higher levels of funding compared to other states. Yet studies reveal that these funding disparities are not strongly correlated with the scientific output or productivity of the regions. This lack of alignment suggests that the unequal distribution of funding is not necessarily tied to the quality of researchers across states.

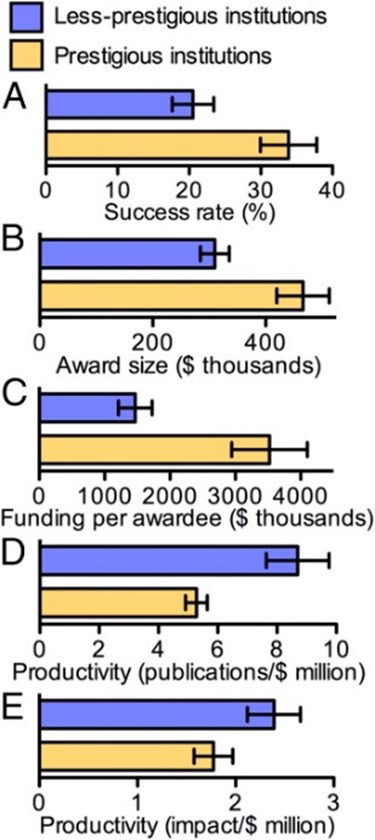

A related criticism of NIH funding is the concentration of awards among a relatively small number of large, well-established research institutions. Prestigious institutions, on average, achieve 65 percent higher grant application success rates and receive 50 percent larger award sizes. Research shows, however, that less-prestigious institutions often outperform their larger counterparts in certain metrics. Less-prestigious institutions on average produce 65 percent more publications per dollar of funding while also achieving a 35 percent higher citation impact per dollar of funding. While prestigious institutions are commonly assumed to be more productive overall, studies suggest that smaller institutions can deliver greater research output and impact relative to their funding.

Two direct measures of research productivity – publications per dollar spent and impact per dollar spent – showcase greater results from less prestigious institutions (defined as specific non-leading medical research institutions).

Source: Wayne. P. Wahls, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

NIH officials in the past have recognized the skewed emphasis toward certain established institutions and researchers, labeling the biomedical research workforce “dangerously out of balance.” The consequences of institutional grant concentration, but lack of effective remediation has left this issue standing.

Bias Toward Previous Awardees, New Investigators, Diminishing Marginal Returns, and Peer Review Concerns

The NIH has long used a peer-review process to determine which research projects receive funding, with the intention of supporting the most promising science. Yet one challenge that has emerged is a bias toward older, established researchers in grant allocation.

According to the Center for Scientific Review, “87% of reviewers stated the NIH has a ‘moderate’ or greater problem with bias in the peer review process.” Biases and concentration of funding can be partially explained by the “Matthew Effect,” whereby established scientists – those who have already achieved recognition or funding – are more likely to receive additional resources due to their established contributions. Regardless of the mechanism, data demonstrate that of all principal investigators (PI) – the lead researchers responsible for the overall design, execution, and management of a research project – 1 percent of PIs receive 11 percent of R-series grants.

Source: Mark Peifer, Molecular Biology of the Cell

Studies find the precise causes behind this bias are complex and not purely linked. Researchers studying the peer review and grant allocation processes for principal investigators find some factors include reviewers’ familiarity with prominent researchers and institutions, as well as a desire to minimize risk by prioritizing track records of established scientists over newer proposals.

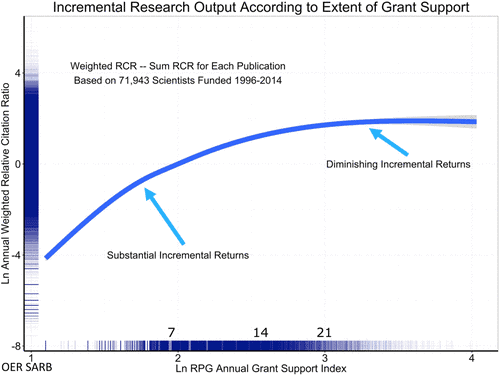

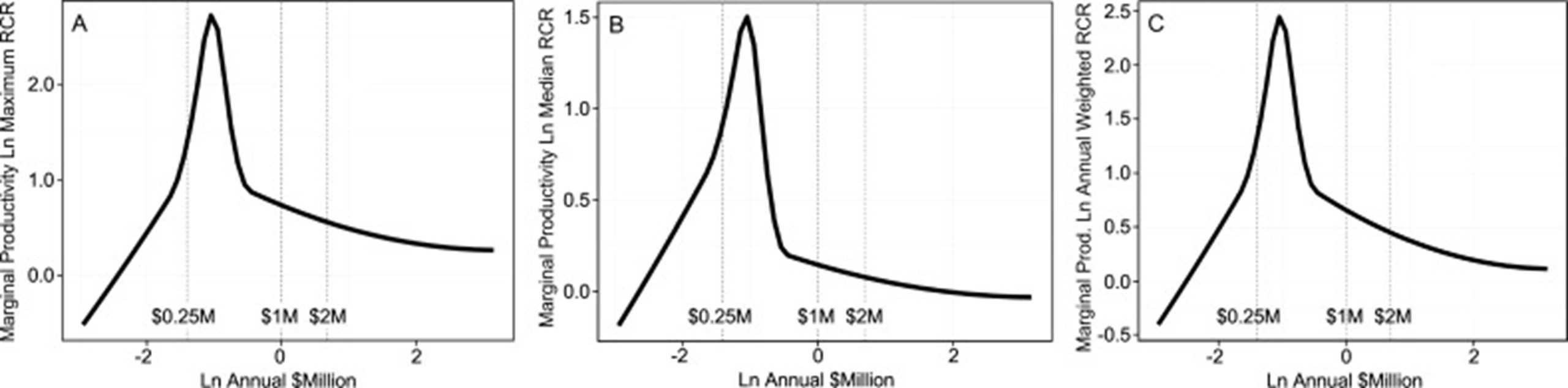

If the current distribution were allocatively optimal, there would be no issue with funding stratification. Research identifies two issues with the current concentrations, however. First, data demonstrate diminishing marginal returns of grant funding for R, P, and U grants. Furthermore, there is an inverse correlation between funding and publication-based/citation impact-based productivity. As such, providing more funding to single researchers may ultimately reduce the efficiency of federal dollars. Again, researchers do not attribute any sole factor to diminishing returns, but the increasing personnel, bureaucracy, and administrative burdens create multiple competing priorities for investigators.

Source: Mark Peifer, Molecular Biology of the Cell

Second, research finds that concentration of funding to established labs may disadvantage promising young researchers without a strong institutional reputation. Since the 1980s, the number of grants awarded to young careers has decreased substantially, despite the doubled NIH budget in 1998 and 2003. Many reviews of research outcomes by age directly link youth with major scientific breakthroughs. The NIH has also acknowledged that withdrawing federal funding from young scientists has potential conseuquences towards scientific production, as many younger scientists obtain only a single R grant. A reduction of single-use R grants decreases efficiency of federal dollars toward science overall, as research reveals that some of the most highly productive and highly cited scientists had only a single grant, and relatively few of the most highly productive were in the top 5 percent of funded researchers. This analysis strongly suggests that the best approach is to bet on the highest number of qualified investigators to optimize human capital.

NIH has taken steps to address this disparity, most notably through the introduction of the Next Generation Research Initiative (NGRI), which is specifically designed to support researchers at the beginning of their careers. The NGRI created a separate category for early state investigators and increases funding priority for investigators who meet the stipulations. The designation allows newer researchers to compete in a separate category, offering them a better chance at securing funding without directly competing against highly established scientists. As noted later, this program has come under criticism and is projected to have a minimal impact on grant concentration.

Mismatch With Emerging Disease Profiles

While NIH generally aligns its funding according to disease impact, critics argue that various funding areas remain misaligned with more contemporary disease burdens. A 2011 retrospective review of funding alignment with disease profiles found a worsening correlation over time between disease burden and NIH funding levels. While the 1996 (DALY) was attributed to 39 percent of the variance in funding, this figure dropped to 33 percent in 2006.

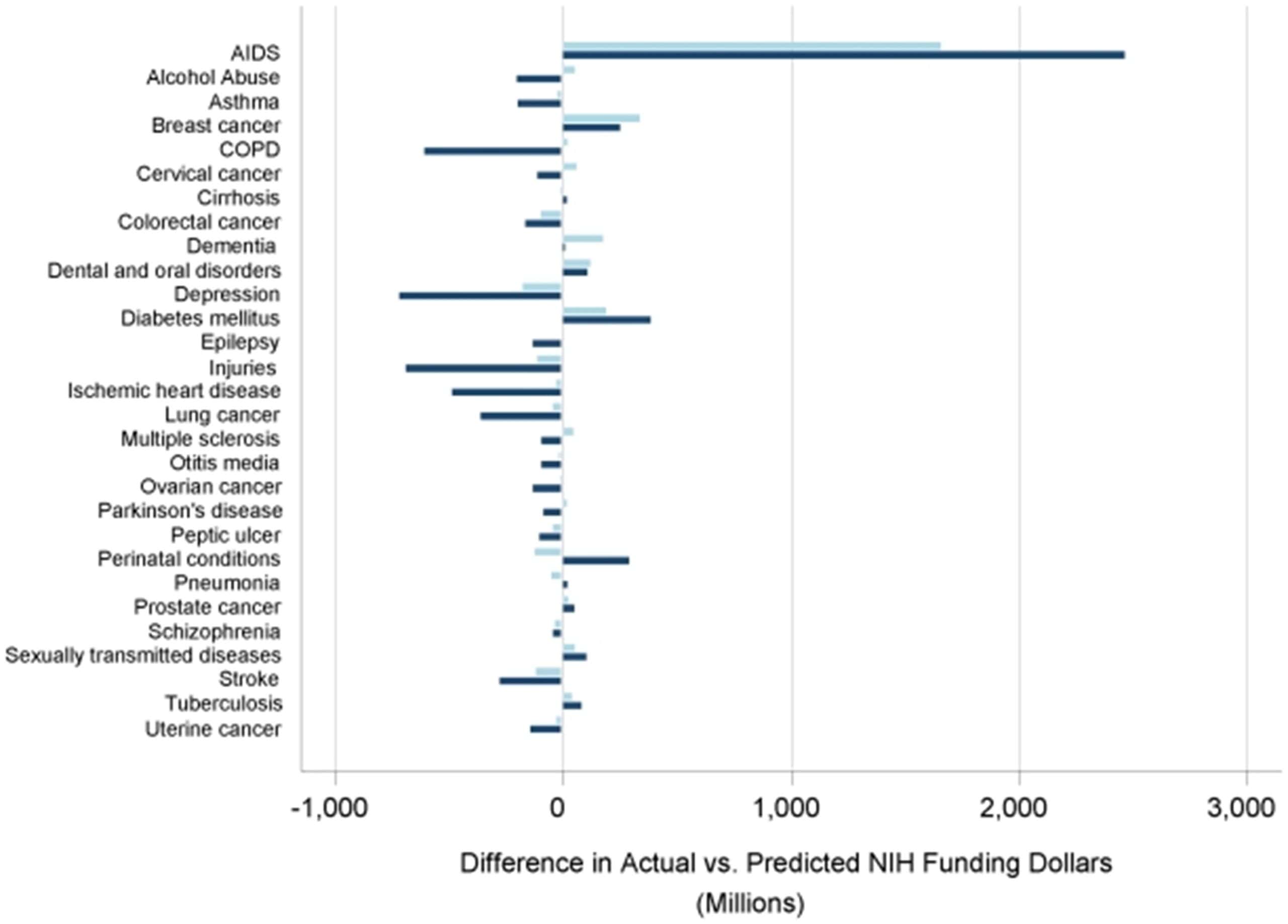

The study also underscored significant discrepancies in funding allocation relative to disease burden. For example, conditions such as HIV/AIDS, which accounted for just 1 percent of disability-adjusted life years (DALYs), received 10 percent of NIH funding, highlighting a disproportionate focus. In contrast, conditions such as depression, injuries, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease – each representing a much larger share of the total DALYs – were allocated considerably less funding. This imbalance suggests a persistent misalignment between funding priorities and the health impact of diseases.

*A comparison of differences between actual and expected funding values as predicted by DALYs burden alone in 1996 (light blue) and 2006 (navy). Negative values reflect actual funding dollars less than expected and positive values represent actual funding dollars more than expected.

Source: Gillum et al., NIH Disease Funding Levels and Burden of Disease

More contemporary analysis of NIH funding according to disease burden found a worsening correlation between disease profiles and funding from 2008–2019. For instance, a 2021 study found the 2019 variance in funding correlated with DALY dropped further to 29 percent. While a one-to-one correspondence is unrealistic, the 1996 figure of 39 percent provides a useful point of comparison, as it reflects a period when alignment between funding and disease burden was comparatively stronger. Reaching or surpassing this level could signify progress toward better alignment, especially given advancements in data collection and health analytics since that time.

Predicting the mechanism behind misalignment is again difficult, but researchers have hypothesized certain relevant factors. A similar study on NIH investment during 2008–2019 found that NIH funding each year is strongly associated with the previous decade’s funding composition, even more so than DALY. For example, the factor most linked to NIH funding in 2019 was the level of funding in 2008 as well as 1996, not the disease burden. This analysis also identified that the same three diseases – HIV/AIDS, digestive diseases, and urological diseases – received substantially more funding in both 2008 and 2019. Assessment of the NIH’s disease allocation data found three diseases in both years that continued to be overfunded: eating disorders, uterine cancer, and psoriasis.

Although it is arguable whether the burden of disease should assume priority in NIH funding decisions, the NIH’s allocation process has been criticized by external medical researchers as arbitrary and insensitive to the burden of disease as early as 1993. Linking the disease burden with funding, while necessary, is not an exhaustive solution to funding reform according to various researchers. Among those advocating for reform, the following concepts have been most prevalent in policy discussions.

Actualizing Proposed Reforms and Medical Researcher Recommendations

The reforms advocated by the medical research community can be broken down into two related categories:

- Empower early-career and mid-career researchers by better balancing funding disparities among institutions and investigators.

- Experiment with cost-effectiveness principles that address diminishing returns of grants.

Optimizing NIH Funding: Balancing Support for Early-Career Researchers and Maximizing Scientific Impact

As previously mentioned, the NIH has received criticism for worsening funding gaps between researchers based on career stage. In response, the NIH the Research Commitment Index (RCI), which then became the Grant Support Index (GSI) in 2017.

The GSI aimed to curb the disproportionate concentration of funds by capping the total grants one investigator could receive. Additionally, the GSI directly addressed the diminishing returns associated with excessive funding for individual investigators to improve overall efficiency. Studies have shown that, beyond $400,000, additional funding yields progressively smaller scientific advances, while others suggest $750,000–$1 million per investigator.

Source: Wayne P. Wahls, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

NIH predictions show positive results when considering a cap, as it notes

…while implementation of a GSI limit is estimated to affect only about 6 percent of NIH-funded investigators, we expect that, depending on the details of the implementation, it would free up about 1,600 new to broaden the pool of investigators conducting NIH research and improve the stability of the enterprise.

The NIH shifted away from the GSI to a different early-career initiative, however: the New Generation Researchers Initiative (NGRI). In contrast, the NGRI sought to directly bolster early-career researchers by expanding funding opportunities for those with fewer than 10 years of NIH support. While this approach has merit, its limitations highlight why additional reforms are needed.

First, by excluding caps on top-funded investigators, the NGRI does not address the structural inefficiencies caused by overfunding a small number of labs. Without such a mechanism, a small number of large labs can continue to absorb significant resources. As such, funds intended for early-career scientists’ risk being drawn from the limited pool available to single-grant labs, potentially undermining the initiative’s intended impact.

Furthermore, evidence suggests that mid-career researchers –those beyond the 10-year eligibility window – are among the most vulnerable yet productive lab groups. The NGRI does not directly address this issue, however, thus limiting the total of researchers it affects.

Source: Charette M, Oh Y, Maric-Bilkan C, Scott L, Wu C, Eblen M et al. Shifting Demographics among Research Project Grant Awardees at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI).

Evaluating Success and Productivity

In the absence of a specific measure like the GSI or RCI, researchers have advocated for the inclusion of a new calculation. The SR/P value – a metric that evaluates success rates normalized by productivity – has been of central focus. This metric’s advantage is that it balances the following competing factors effectively. It provides a level playing field for researchers to compete for grants, accounts for differences in the value of research among various groups and attempts to maximize taxpayer dollars. According to a review of the costs of biases by the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, the SR/P “provides a straightforward and impartial” method of balancing key needs.

The metric itself is flexible, as one can group by various categories (race, gender, age, institution or state) and utilize any measure of productivity that is desired (publication rate or citation impact per unit of funding). A target SR/P value would be set for researchers, and the NIH would adjust success rates and award sizes of institutions to achieve parity or near parity of their SR/P values. While success rates and award sizes could still vary among institutions, according to their productivity-based merit, up to but not exceeding the point at which their SR/P values depart from the target range, these changes would not alter the peer review process itself and would partially satisfy the calls for reform from researchers.

Looking Forward

The NIH plays a pivotal role in driving biomedical advancements and improving public health, yet researchers both within and external to NIH suggest there are opportunities to refine its funding strategies to achieve even greater impact. Proposals include strengthening the alignment of funding with evolving disease burdens, enhancing the peer review process, and addressing disparities in allocation. With these changes, researchers hope the NIH could potentially optimize research investments toward the most pressing health challenges.

While initiatives like the NGRI have made strides in supporting early-career researchers, further reforms – such as implementing data-driven funding strategies and ensuring resources are directed toward the most promising research – could enhance the effectiveness of NIH investments. Such improvements could help accelerate scientific breakthroughs, advance medical innovation, and deliver meaningful health outcomes.