Week in Regulation

September 16, 2019

Asylum Application Proposal Dominates Week

Last week marked yet another iteration of a now-familiar trend: one rulemaking taking an outsized position amongst an otherwise ho-hum set of regulations. This week’s main item is a proposed rule out of the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) regarding asylum seekers’ ability to pursue employment that constitutes billions of dollars in potential economic impact. All other rulemakings netted out to just under $10 million in cost savings. Across all proposed and final rules, agencies published $4.4 billion in total net costs and added 37,904 hours of annual paperwork.

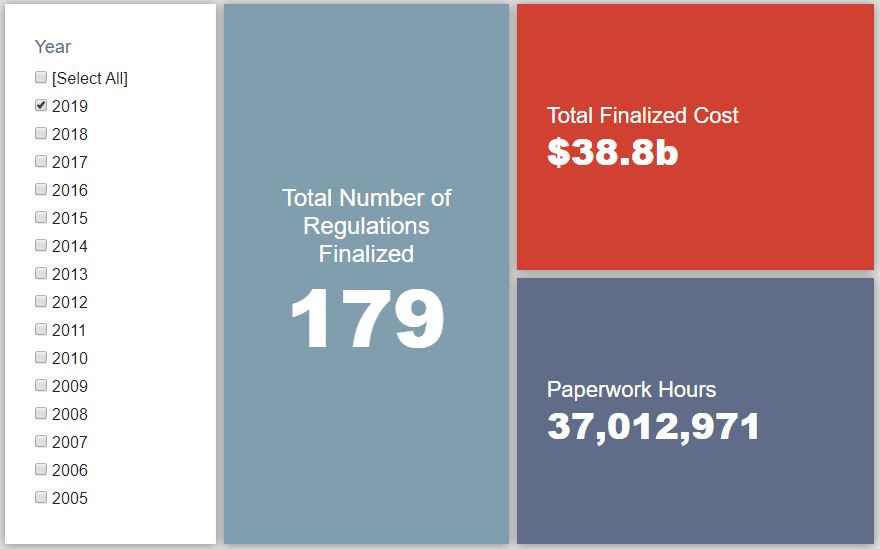

REGULATORY TOPLINES

- New Proposed Rules: 35

- New Final Rules: 88

- 2019 Total Pages: 48,461

- 2019 Final Rule Costs: $38.8 Billion

- 2019 Proposed Rule Costs: -$774.5 Million

TRACKING THE REGULATORY BUDGET

The DHS proposal, at its core, would lift the 30-day limit on consideration of Form I-765 (or the Application for Employment Authorization for asylum seekers). DHS claims this change is necessary to ensure “sufficient time to receive, screen, and process applications.” Letting the review process continue, however, means that applicants are outside of the legal labor pool until a determination is made which results in lost wages for them and lost productivity for potential employers. DHS provides a range of estimates that entail some mix of transfer and cost effects based upon uncertainty surrounding whether employers would find replacement labor. For this proposed version, the agency settles on $387.4 million (the midpoint of the range of effects) in potential annualized costs; the present value over 10 years would be nearly $4.4 billion. Since this is still a proposed rule, these costs do not apply to the fiscal year (FY) 2019 regulatory budget under Executive Order (EO) 13,771.

The most notable final rule that does apply to the FY 2019 budget is an acquisition process rule affecting the Department of Defense, General Services Administration, and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (the agencies). This rule eliminates a particular requirement in the process and thus makes it easier for government contractors to bring on subcontractors. The agencies estimate that this could yield roughly $1.2 million in annual savings under EO 13,771. That figure, however, includes savings to the federal government as well. The annual savings to private entities is only about $800,000, or $14.6 million in present value.

So far in FY 2019 (which began on October 1, 2018), there have been 62 deregulatory actions (per the rubric created by EO 13,771 and the administration’s subsequent guidance document) against 35 rules that increase costs and fall under the EO’s reach. Combined, these actions yield quantified total net costs of roughly $11.6 billion. This total, however, includes the caveat regarding the baseline in the Department of Agriculture’s “National Bioengineered Food Disclosure Standard.” If one considers that rule to be deregulatory, the administration-wide net total is approximately $4.9 billion in net costs. The administration’s cumulative savings goal for FY 2019 is approximately $18 billion. There is now less than a month left in the fiscal year.

THIS WEEK’S REGULATORY PICTURE

This week, the Federal Motor Carrier Safety Administration (FMCSA) permanently ends an arbitrary component of the Hours of Service (HOS) rules.

In a final rule published in the Federal Register on September 12, the FMCSA – the agency within the Department of Transportation that oversees, among other things, the long-haul trucking industry – repealed part of the restart provision of the HOS rules. By law, drivers must have a period of 34 consecutive hours off duty once per week in order to “restart” the clock on a new week.

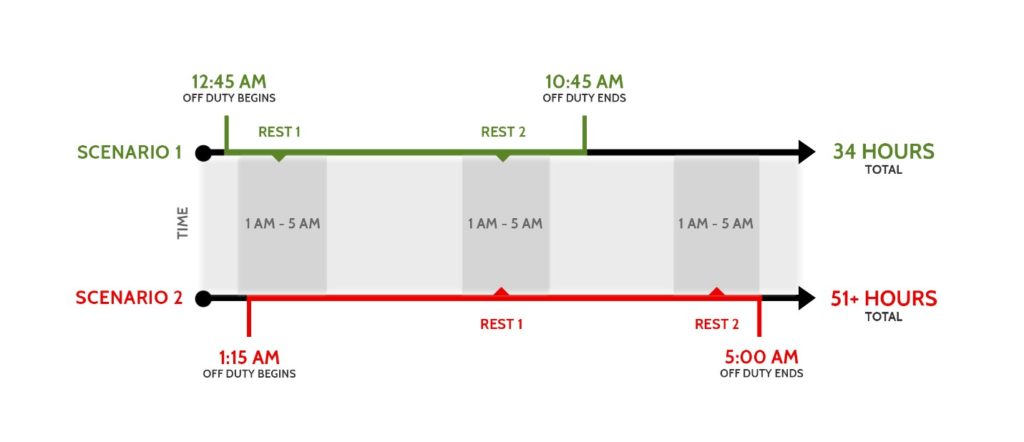

In 2011, the Obama Administration’s FMCSA added another layer to the restart – the 34-hour period had to contain the hours between 1 a.m. and 5 a.m. on consecutive days. This had the effect of extending the restart period beyond 34 hours in some cases. The graphic below shows how the provision could prolong the restart period depending on what side of 1 a.m. a driver went off duty.

In the scenarios above, a driver ending at 12:45 a.m. Saturday could begin their next week 34 hours later at 10:45 a.m. Sunday. A driver ending just 30 minutes later, would have to wait until 5:00 a.m. Monday to begin – a total off duty period of more than 51 hours.

The trucking industry was not happy about the change, which it argued affected scheduling and limited drivers’ ability to choose when they wanted to start a new week. There is nothing that says a driver must begin duty again at 34 hours, but the added layer would have prevented drivers from starting at the most convenient time – the driver in scenario 2, for example, might choose 9 p.m. Sunday when traffic would be much lighter.

In response to the criticism, Congress included language in a funding bill in 2014 to suspend the rule until FMCSA performed a study to verify its claim that the 1-5 a.m. requirement would actually improve safety, which was the original justification for the provision. In January 2017, a report was finalized showing the requirement did not significantly affect safety outcomes versus the pre-2011 provision. Accordingly, FMCSA finally repealed the provision this week.

TOTAL BURDENS

Since January 1, the federal government has published $38 billion in total net costs (with $38.8 billion in finalized costs) and 42.7 million hours of net annual paperwork burden increases (with 37 million coming from final rules). Click here for the latest Reg Rodeo findings.