Week in Regulation

September 7, 2021

Fuel Efficiency Picture Becomes More Complete

Last week – in what is becoming quite the pattern – the major regulatory fireworks came from a single proposed rule. This proposal, however, has a rather interesting wrinkle to it. The action in question is the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s (NHTSA) proposed update to Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) standards for light-duty vehicles. Such a rulemaking has, in recent years, come in the form of a joint action with the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). This iteration comes as a separate (albeit complementary) action from the EPA proposal published a few weeks ago – with its own notable impacts. Across all rulemakings, agencies published $33.7 billion in total net costs and added 7,229 paperwork burden hours.

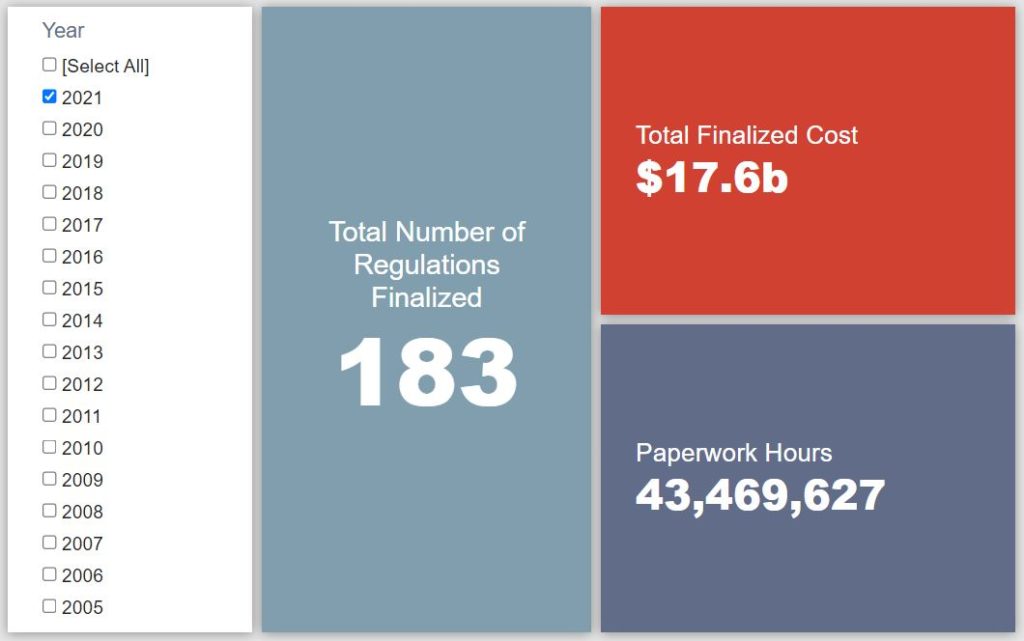

REGULATORY TOPLINES

- Proposed Rules: 39

- Final Rules: 73

- 2021 Total Pages: 49,819

- 2021 Final Rule Costs: $17.6 billion

- 2021 Proposed Rule Costs: $176.8 billion

NOTABLE REGULATORY ACTIONS

As noted above, the main highlight of the week was the official publication of NHTSA’s proposed rule regarding “Corporate Average Fuel Economy Standards for Model Years 2024–2026 Passenger Cars and Light Trucks.” One could be forgiven for having a sense of déjà vu with the EPA proposed rule regarding greenhouse gas emissions for such vehicles hitting the pages of the Federal Register earlier in August.

Rulemakings on this topic over the past two administrations have been joint actions; this latest version splits it into separate documents. On a broad level, this is largely due to specific differences in each agency’s statutory mandate and authority. But what does it mean for the economic impact? The following passage from the proposal’s Preliminary Regulatory Impact Analysis (PRIA) provides a succinct explanation:

For purposes of this PRIA, we have only attempted to report costs and benefits for the proposed NHTSA CAFE standards, and not also EPA’s proposed standards. We refer readers to EPA’s documents for more information about their proposal and its effects, and note that costs and benefits of the two programs will largely overlap [emphasis added], since manufacturers will take many actions that respond to both programs simultaneously.

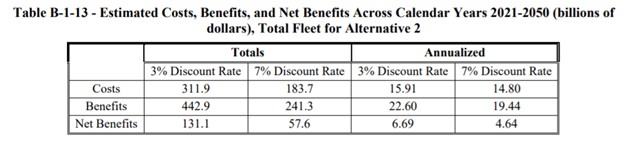

Given this explanation, for the purposes of tallying the estimated costs for RegRodeo, it is important to discern where that overall begins and ends to avoid double-counting. For NHTSA, much of the primary analysis focuses on the economic impact imposed over the lifetime of the covered model years while EPA’s analysis focuses more on calendar years. There is, however, a portion of NHTSA’s analysis that provides the economic impact under essentially the same framework as EPA’s:

Therefore, with this and the noted overlap between the agencies in mind, it is reasonable to ascribe an additional $33.7 billion in total costs to this measure on top of EPA’s estimated $150 billion in total costs.

TRACKING THE ADMINISTRATIONS

As we have already seen from executive orders and memos, the Biden Administration will surely provide plenty of contrasts with the Trump Administration on the regulatory front. And while there is a general expectation that the new administration will seek to broadly restore Obama-esque regulatory actions, there will also be areas where it charts its own course. Since the AAF RegRodeo data extend back to 2005, it is possible to provide weekly updates on how the top-level trends of President Biden’s regulatory record track with those of his two most recent predecessors. The following table provides the cumulative totals of final rules containing some quantified economic impact from each administration through this point in their respective terms.

![]()

Similar to the preceding week, last week saw limited change on the final rule front for the Biden and Trump Administrations. The most notable shift across any of the administrations covered once again came from the Obama years. In this case, the cost column saw a notable spike. A Department of Energy rule on energy efficiency standards from vending machines accounted for the bulk of that increase with roughly $470 million in total costs.

THIS WEEK’S REGULATORY PICTURE

This week, a federal court decision results in another watery mess for the definition of “Waters of the United States” (WOTUS).

On August 30, a judge in the U.S. District Court for the District of Arizona vacated the Trump Administration’s Navigable Waters Protection Rule, the most-recent effort from the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the agencies) to define WOTUS.

The term’s definition is important because it determines where the federal government can prohibit or require permits for certain discharges or activities, such as land development. While the agencies have issued what they presumed to be clear definitions several times in the past, courts have struggled to ascertain exactly how far Congress intended to extend the federal government’s reach.

The Trump Administration’s rule scaled back an Obama Administration rule that greatly expanded what geographical features are considered federal waters. The Obama Administration’s rule, however, was itself of murky legality but was repealed by the Trump Administration before making its way to the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the district court ruling, the judge determined that because the Trump Administration’s rule was contrary to the recommendations of the agencies’ experts, it was arbitrary and capricious. That determination remanded the rule back to the agencies to reconsider (for its part, the Biden Administration had already announced it would revise the definition).

The judge also vacated the Trump Administration rule, reasoning that environmental harm could occur if the agencies continued to enforce the rule while it was revised. The judge cited a figure from the agencies that 333 projects that would have required permits under the previous definition no longer did under the Trump Administration rule and could result in environmental harm.

While the Trump Administration’s rule defining WOTUS was vacated, the court did not rule an earlier Trump Administration rule repealing the Obama Administration’s rule. The court will continue to hear arguments on whether that repeal should stand. The resulting situation is increased uncertainty over what is — and what isn’t — a WOTUS.

Of course, even when the Biden Administration finalizes its revamped definition a new legal battle will ensue.

TOTAL BURDENS

Since January 1, the federal government has published $194.4 billion in total net costs (with $17.6 billion in new costs from finalized rules) and 44.9 million hours of net annual paperwork burden increases (with 43.5 million hours in increases from final rules).