Weekly Checkup

July 21, 2023

An Open Letter to the Senate 340B Working Group

A few weeks ago, a bipartisan 340B Drug Pricing Program working group of six senators released a request for information (RFI) on the program, asking for ways it can be reformed. The deadline for submission is July 28, and while this author will submit an official response, let’s go over what those reforms can and perhaps should be.

The American Action Forum has written extensively about the 340B Drug Pricing Program – highlighting how the program works, what the challenges are, what legal battles surround the program, how the program affects drug prices – as well as authored myriad Weekly Checkups covering miscellaneous parts of the program. To recap, the 340B Program was created by Congress in 1992 as a fix to the Medicaid Best Price rule which ended charitable drug donations to hospitals by pharmaceutical companies. The program requires pharmaceutical companies that participate in Medicaid to provide discounts to covered entities (CEs), such as hospitals, on drugs, with the intention that CEs would use these savings to “stretch scare federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.” In the last 25 years, and especially since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, which expanded the eligibility criteria, the 340B Program has exploded in size – from 583 CEs in 2005 to around 12,700 CEs today. These CEs consist of non-profit hospitals and their numerous downstream entities (any off-site providers that are part of a qualifying hospital system, as well as contract pharmacies, are included under the CE umbrella), federally qualified health centers, and a variety of community health clinics.

The senators asked six important questions that all deserve in-depth answers, but we’ll focus on just one: “What specific policies should be considered to ensure that the benefits of the 340B Program accrue to covered entities for the benefit of patients they serve, not other parties?” To ensure 340B savings are benefiting the intended patients, Congress needs to enact stricter guidelines on who can qualify as a 340B CE and a 340B patient. Right now, for a hospital to qualify as a CE, it only needs to be a non-profit hospital that contracts with a state or local government with 11.75 percent of its patients being low-income Medicare and Medicaid patients. One would be hard-pressed to find a non-profit hospital that didn’t meet this standard. It also means that hospitals that aren’t true safety-net hospitals (the original targets of the 340B Program) can participate. This low standard is likely why 340B hospitals underperform national averages of charity care – in 2017, it was found that 340B hospitals put only 1.66 percent of patient revenues toward charity care, while the national average was 2.06 percent. Increasing the number of low-income patients that hospitals need to qualify will ensure that 340B dollars go to those who need them most. Additionally, the standard for being a qualifying patient is to simply have medical records with a given CE – so basically every patient at a 340B hospital counts. It is worth exploring shifting the eligibility standard for a 340B discount to be patient-centered rather than entity-centered. By this, I mean the type of patient (e.g., the indigent and uninsured) receiving the drugs would determine whether an entity can receive a discount on those drugs, rather than the entity receiving a discount automatically for all drugs prescribed to all patients. While admittedly controversial, under this proposal, hospitals that primarily serve these populations would retain their 340B dollars. At the very least, patient-centered eligibility deserves study.

The 340B Program isn’t going away anytime soon, and remains a life line for many safety-net hospitals struggling to keep their doors open. But when some of the most financially healthy hospital systems in the country can participate, with little evidence that those dollars are going toward indigent and uninsured patients, it’s not surprising when pharmaceutical manufacturers stop honoring questionable discounts. If Congress wants to ensure the longevity of the 340B Program, a good place to start is by strengthening eligibility requirements to ensure only hospitals that truly need the money receive it.

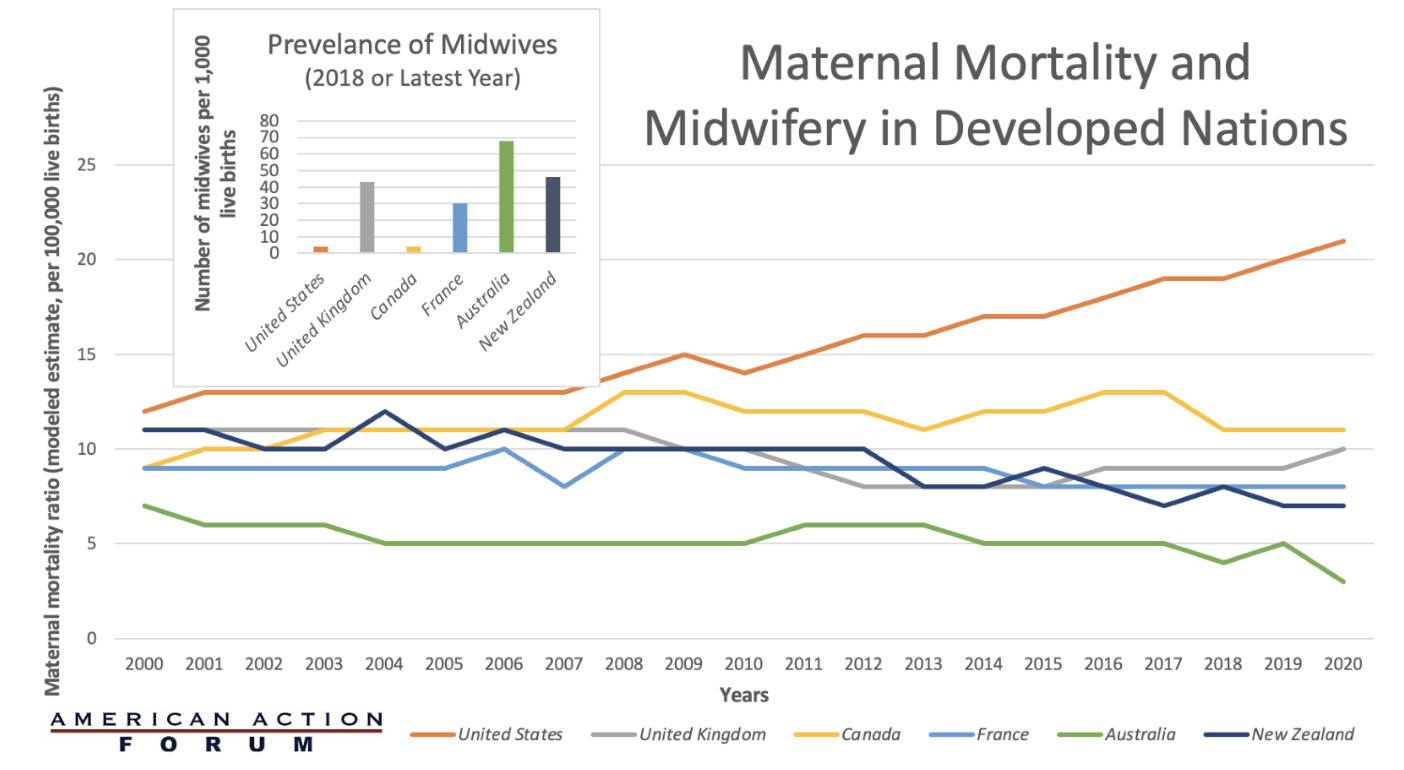

Chart Review: Maternal Mortality and Midwifery in Developed Nations

Sophia Marasco, Health Care Policy Intern

The United States has the highest maternal mortality ratio compared to other developed nations, and 4-in-5 pregnancy-related deaths in the United States are preventable. This raises the question: What is the United States doing differently from other high-income countries with better pregnancy outcomes? The chart below compares the World Bank’s estimate of six developed maternal mortality ratios (deaths while pregnant or within 42 days of pregnancy termination per 100,000 live births) to the number of midwives available per 1,000 live births. As the chart demonstrates, the United States has the highest maternal mortality ratio among similarly wealthy countries and the least number of midwives available. Australia has the lowest maternal mortality ratio and the greatest number of midwives. The number of midwives is only one variable that may shed light on the U.S. maternal mortality crisis; differences in the availability of maternal care after delivery, paid leave, quality of prenatal care, prevalence of single mothers, method of delivery, severity of chronic disease, and several other factors may also explain why these countries have such disparate maternal mortality ratios.

Sources: The World Bank and Commonwealth Fund