Weekly Checkup

July 26, 2019

Drug Prices, Arbitration, and Leveraging the Market

This week saw the long-awaited arrival of the Senate Finance Committee’s bipartisan drug pricing legislation. While the package contained some particularly worthwhile reforms (including some originally suggested by AAF), and some especially problematic provisions, one unappealing idea for reducing drug prices was mercifully absent: arbitration. Also this week, however, a senior aide to House Speaker Nancy Pelosi outlined the key components of drug-pricing legislation House Democrats hope to consider after the August recess, and arbitration is very much alive as part of that package.

Fortuitously, AAF hosted a panel this week on exactly that topic with experts (including your dedicated Weekly Checkup author) discussing what exactly arbitration is, and the merits—or lack thereof—of applying it to drug prices.

Arbitration, simply put, is a legal means of resolving civil disputes arising from failed negotiations. Democrats have long called for the Secretary of Health and Human Services to be allowed to negotiate directly with drug companies for lower prices. But even if the secretary could negotiate legally, it’s not clear how much leverage he would have, short of simply refusing to cover certain drugs for seniors. Progressive policymakers, recognizing this reality, have come up with several ways to give the secretary more power in negotiation, arbitration among them. In theory arbitration would kick in after the secretary attempted and failed to negotiate a discounted rate on a drug. The secretary and the manufacturer would each submit a proposed price to an arbitrator, who would then choose between them.

Arbitration seems simple enough on the surface, but there are a host of questions about how the arbitration process would be structured. For example, how would the process be triggered? It could follow attempted negotiation, but some have suggested sending manufactures directly to arbitration without a negotiation process for any drug with a list price over a particular (arbitrary) dollar amount. Further, which of the several types of arbitration would be used? And how will an arbitrator be chosen? Would the arbitrated price apply to Medicare Part D, Part B, both, or even the commercial sector, as some activists have called for? For a more thorough analysis of these and other questions, read my short paper on the topic here.

But before we get too far into the mechanics, we should consider whether arbitration takes public policy in the direction we want to go.

Government negotiation and the use of arbitration would reshape the federal government’s relationship to the market and to its citizens. It would be a marked repudiation of current practice, where the federal government typically does not capriciously set prices for private sector goods just because of either popular opinion or federal budget constraints. And it would chart a trajectory for public policy that sets the government in opposition to the market, instead of looking for ways to leverage those forces.

Before answering technical questions, therefore, we need to ask the more fundamental questions about the implications of this policy. Do we believe that markets work generally? Do market forces lead to correct evaluations of value and better outcomes? Or do we want a command economy directed by government bureaucrats? The health care market is by no means a completely free and unfettered market, but that does not mean we should actively erode market forces. Government-directed arbitration would involve bureaucrats essentially making decisions about the value of a prescription drug instead of patients and doctors. The United States has avoided this approach up to now, and there are good reasons to think it shouldn’t move this direction in the future.

Chart Review

Ryan Haygood, Health Policy Intern

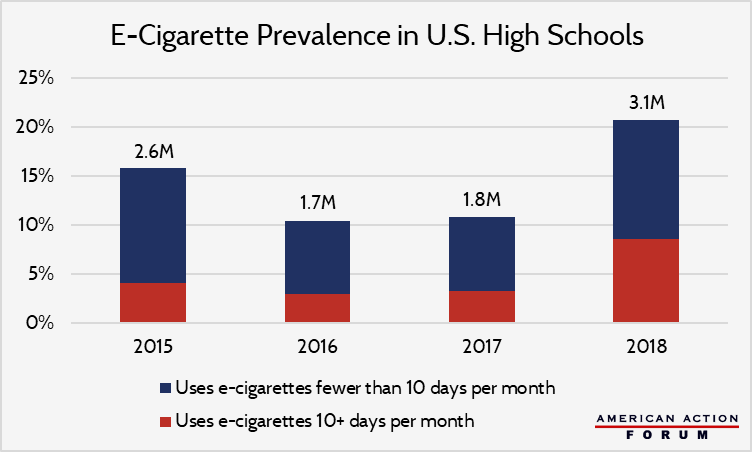

The House Oversight Committee questioned JUUL executives on Thursday as part of a two-day hearing entitled, “Examining JUUL’s Role in the Youth Nicotine Epidemic.” E-cigarette use among U.S. high school students grew at 78 percent from 2017 to 2018, breaking a brief slump in popularity since 2015. Between 2015 and 2018, frequency of use has also increased by 50 percent – from 8 to 12 days per month on average – as shown below by the increasing share of users who report 10 or more days of use per month. The New York Times has reported on efforts from JUUL to encourage e-cigarette uptake through youth programs. For its part, the Food and Drug Administration last year began reorienting its highly effective anti-cigarette campaign, “The Real Cost,” to educate youth about e-cigarettes’ risks, which include nicotine addiction, harms to brain development, and diminished lung health.

Media

AAF’s Deputy Director of Health Care Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes explains why Medicare Part D should be reformed as well as AAF’s proposal for how to change incentives to lower drug costs.

Worth a Look

Wall Street Journal: Consumers Will Be Able to Pay for Doctor Visits on Their Phones, Via Anthem

Health Affairs: Sending The Wrong Price Signal – Why Do Some Brand-Name Drugs Cost Medicare Beneficiaries Less Than Generics?