Weekly Checkup

October 7, 2022

Hospital Closures

The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided $175 billion to hospitals to help them treat patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a study published earlier this year on the Journal of the American Medical Association’s Health Forum, these funds helped offset a massive negative operating margin: -7.4 percent in 2020, compared to -1.0 percent in 2019. With CARES money, hospitals’ nonoperating revenue (revenue not from patient-care services) grew from 4.4 percent in 2019 to 10.3 percent in 2020. So, hospitals received a massive cash infusion during the worst days of the pandemic and should be doing fine, right?

Not really. Numbers are hard to come by for all hospitals (though the Sheps Center at the University of North Carolina tracks rural hospital closures), but there is general agreement in the health care field that hospital closures have been growing over the past few years, particularly during the pandemic. Hospitals aren’t just closing; an overlooked side effect of the pandemic is hospitals cutting services. Becker’s Hospital Review has a handy list of hospitals and hospital systems that just this year have cut back on services or closed locations, with big names among them: The Mayo Clinic, Ascension, and University Hospitals in Cleveland. My own home state of Indiana is losing inpatient and intensive care pediatric services at one hospital and seeing an entire health system leave a county. More prominently, Atlanta, Georgia received a nasty shock when its citizens (and government leaders) awoke to the news in September that the Atlanta Medical Center, a major care provider for Atlanta’s low-income population, will be shuttered in November by its parent system Wellstar.

What’s going on here? As the Sheps Center notes, rural hospitals have been struggling for a long time, but urban hospitals are starting to feel the pinch, as well. The answer is complicated but boils down to one thing: the COVID-19 pandemic. Intensive care units remained flooded with expensive COVID-19 patients for two winters in a row. More important, labor costs for hospitals have surged 37 percent, as burned-out nurses either quit the profession entirely or became highly paid contract nurses. One can’t blame the nurses: Contract nurses’ median hourly wages rose from $64 per hour in 2019 to $132 per hour in 2022, while employed nurses only saw a rise from $35 per hour to $39 per hour during the same period. In fact, the use of contract labor at hospitals has spiked from 2 percent of labor expenses in 2019 and 2020 to 11 percent in 2022. This was almost unavoidable – hospitals had to fill a preexisting labor shortage to keep up with the initial COVID-19 case volume, and as more physically and emotionally exhausted doctors and nurses quit while the pandemic raged, contract labor became a necessity. Naturally, hospitals themselves also blame payment cuts in Medicare. Of note, one suspected culprit, the drop in elective surgeries, turned out not to be that damaging: Surgery volume returned to 2019 levels relatively quickly after hospitals’ initial March-April 2020 cancellation of nonessential surgeries.

$175 billion is a lot of money, and thoughtful policy wonks should be asking where it all went. It’s hard to believe all of it went directly to patient care. Congress should be directing a lot of questions to hospital administrators, who account for 25 percent of hospital expenditures. As we work through COVID-19’s aftermath, policymakers should address two key questions: how to stabilize hospital services, and how, exactly, hospitals spent nearly $200 billion in federal pandemic aid.

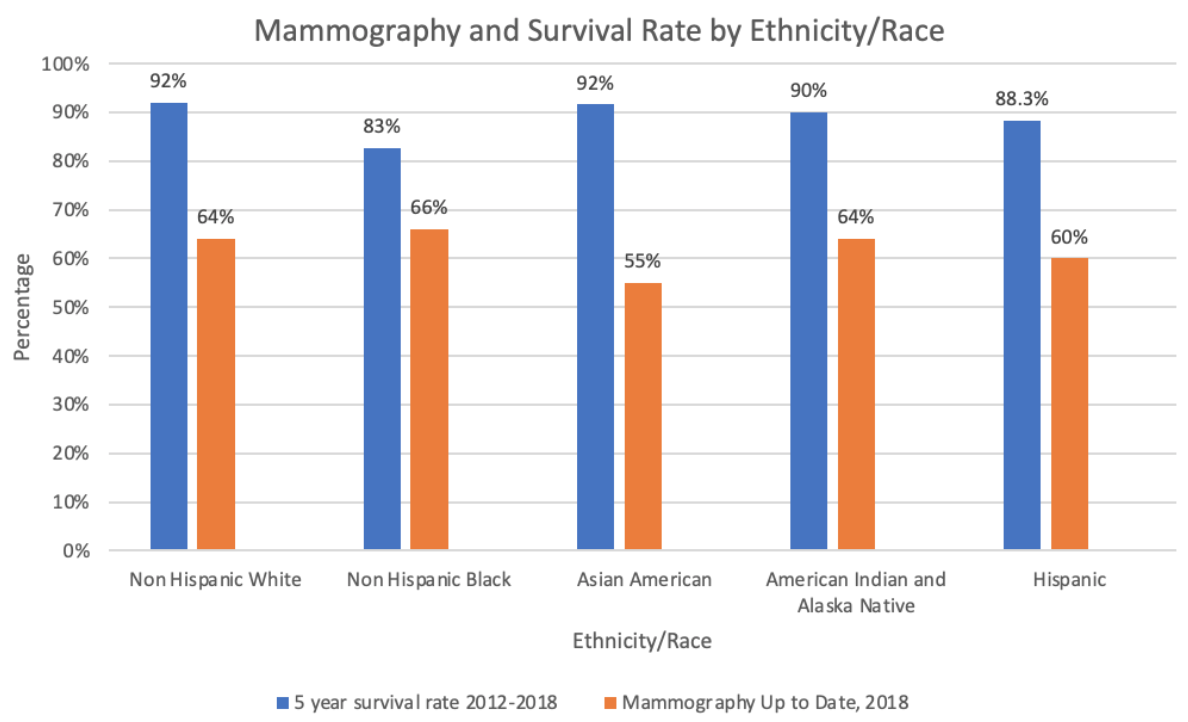

Chart Review: Comparison of Mammography and Breast Cancer Survival by Ethnicity/Race

Danielle Bartolotta, Health Care Policy Intern

A recent study by the American Cancer Society found that mammography as a form of preventative care significantly reduces deaths from breast cancer, which is the second leading cause of cancer death among women. Experts recommend that women of all ages be up to date with screening guidelines. As seen in the chart below, however, non-Hispanic Black women tend to be the most up to date with their mammograms, yet have the lowest 5-year survival rate. This mismatch is also demonstrated in the data for Asian American women, who have the lowest compliance for receiving routine mammograms yet have the highest survival rate. Policymakers should investigate variations among these groups in access, cost, and quality of care to determine what is contributing to these disparate outcomes.