Weekly Checkup

July 29, 2022

How Do You Solve a Problem Like the REH-a?

By any measure, rural hospitals are hurting. Data from the Sheps Center for Health Services Research at the University of North Carolina shows 140 rural hospital closures since 2010. To stem this trend, the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021 established the Rural Emergency Hospital (REH) program, and this June the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) released new payment and enrollment rules in its latest proposed Outpatient Prospective Payment System rule. The REH program is well-intentioned, but between hospital hesitancy and systemic problems inherent to rural health care, it probably won’t do much to slow rural hospital closures.

The REH program is intended to keep emergency and outpatient services available in rural areas and aims to accomplish this by requiring participating hospitals to eliminate costly-to-maintain inpatient services. Under the statute, eligible entities for the program include Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs) and designated rural hospitals with fewer than 50 beds. While REHs will provide emergency department services, observation care, and covered outpatient services, they will provide minimal acute care inpatient services—specifically, only skilled nursing facility services. These changes will allow hospitals to get rid of their inpatient beds, which is a requirement of participating in the REH program, as the beds are a key driver of costs.

There are several carrots for hospitals to join the program. For covered outpatient services, participating hospitals will receive an additional 5 percent payment on top of the standard Medicare outpatient fee schedule, with no additional coinsurance for beneficiaries. Participants will also receive an additional flat monthly “facility fee,” which will be established in 2023 and then increased based on the percentage increase of CMS’ hospital market basket. Despite the program’s benefits, rural hospitals in particular are concerned that they may end up worse off. First, rural hospitals depend more on outpatient revenue than other hospitals, and Medicare outpatient revenue in particular, so it is very unlikely that the REH program’s 5 percent bump to outpatient services will be enough to make up for the hospitals’ elimination of inpatient revenue. Second, as the REH program’s facility fee isn’t yet established, rural hospitals and CAHs are concerned that it will not be set high enough; rural hospitals claim the facility fee will need to be around $2 to $3 million per year to offset their losses. Finally, the pandemic made empty inpatient beds in rural hospitals invaluable as metropolitan hospitals overflowed with COVID-19 patients, so state and local leaders may now be reluctant to let rural hospitals get rid of these beds. Additionally, hospitals themselves are unwilling to give up beds they view as important for patients in recovery from surgery or illness.

The REH program appears to be yet another federal attempt at trying to put out a fire by pouring money on it.Many rural hospitals aren’t surviving because they are simply too big for the populations they serve. Running a hospital comes with a host of state and federal regulations—and thus a host of compliance costs—and rural populations do not provide the volume of patients and revenue needed for these hospitals to survive. A hospital with no inpatient beds plays it fast and loose with the term “hospital” and a new program isn’t going to change the underlying systemic challenges in rural health care. CAHs, of which 85 percent are rural, are reimbursed based on cost and are still struggling to keep their doors open. They were also the government’s previous attempt to solve the rural hospital closure crisis and have so far been unsuccessful in that mission. If we want to preserve critical emergency services and primary care in rural areas, we need to replace the hospital-centric model of care with one that is more flexible and sustainable.

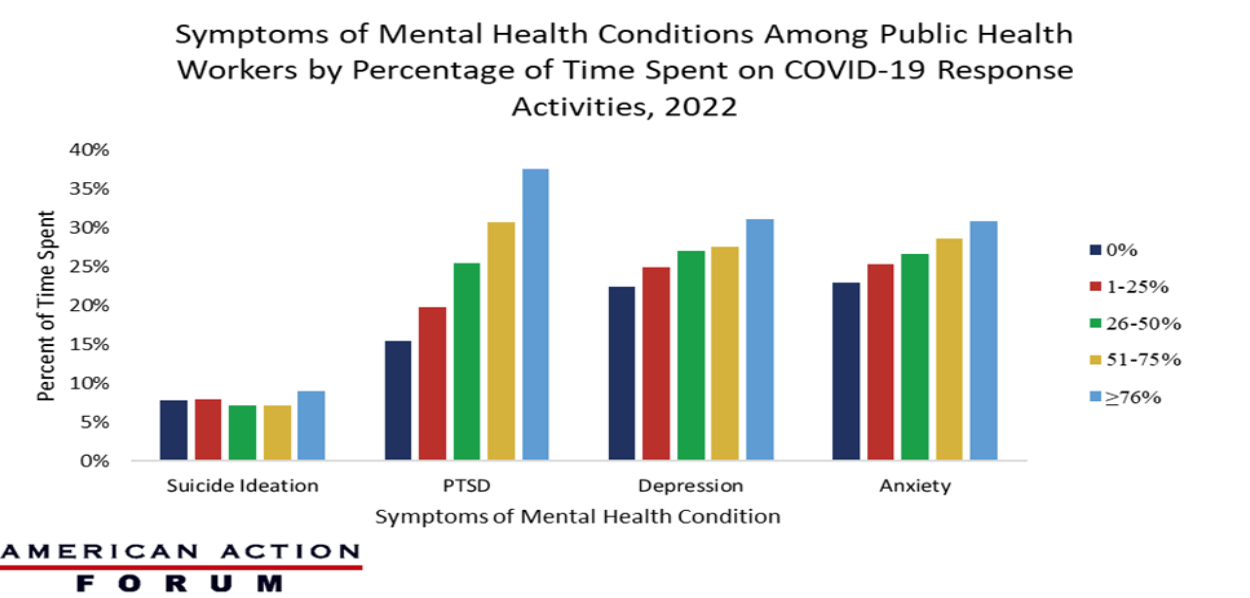

Chart Review: Symptoms of Mental Health Conditions Among Public Health Workers

Evan Turkowsky, Health Care Policy Intern

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recently reported its findings on COVID-19 responders’ adverse mental health symptoms. Specifically, the CDC reported its findings from a March 2022 survey on the mental health of public health workers involved in the COVID-19 response at the state, tribal, local, and territorial levels. The report found that approximately 48 percent were experiencing at least one symptom of a mental health condition: 27.7 percent reported symptoms of depression, 27.9 percent anxiety, 28.4 percent post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and 8.1 percent suicidal ideation. As seen in the chart below, as the amount of time spent by public health workers on COVID-19 response activities increased, the percentage of workers experiencing anxiety, depression, and PTSD also grew. Respondents who had spent at least 76 percent of their time working on COVID-19 response activities were more likely to experience depression (31 percent), anxiety (31 percent), and PTSD (38 percent) than public health workers not working on COVID-19. It is worth noting that for some symptoms of mental health conditions, time spent on the COVID-19 response did not substantially increase the incidence of these symptoms. This indicates that the impact of COVID-19 can be seen across the public health sector, regardless of the time spent on response. Of note, however, the rates of PTSD for from the pandemic show a significant correlation to the time workers spent on response efforts. These numbers indicate that the mental health impact of COVID-19 has caused long-term exhaustion in the public health sector.

Data Source: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention