Weekly Checkup

March 21, 2025

Improper Payments: The Dilemma of Pay First, Check Later

Last week, a subcommittee of the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform held a hearing to discuss its multi-year investigation into fraud in government payment systems and several possible bipartisan reforms. At the heart of the subcommittee’s investigation were improper payments in Medicare and Medicaid. Let’s review improper payments to understand what they are, why we keep hearing about them in news headlines, and two ways Congress can approach this issue going forward.

Improper payments in Medicare and Medicaid are any payments sent to hospitals and providers that don’t satisfy the programs’ myriad program requirements and are therefore sent incorrectly. Payments considered “improper” generally fall into one of three categories: overpayments, underpayments, and insufficiently documented payments. While some improper payments are caused by deliberate fraud or abuse, improper payments are primarily a result of missing or insufficient documentation or administrative errors.

Improper payments are not a new issue. The Government Accountability Office calculated that over the past 20 fiscal years, the federal government has paid more than $2.8 trillion in improper payments. While these improper payments span all sectors of the federal government, over 53 percent of reported fiscal year 2024 improper payments originated from the Medicare and Medicaid programs. This equates to more than $85 billion spent on insufficiently documented or erroneous payments.

It’s reasonable to ask, therefore, why does the issue of improper payments in health care continue to persist? While the dollar value paints a clear picture of the problem, a solution isn’t quite as obvious. This is because Medicare and Medicaid are specifically designed to give providers and care centers sufficient leeway to care for patients. Both programs are considered “treatment forward” programs – meaning they treat first and ask questions later – as mandated by their prompt payment regulations. As these regulations generally hold that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) must pay providers within 30 days of receipt of a claim, improper payments often aren’t identified until after an audit. This leaves CMS in a tough spot, especially since the agency only has 60 days once an overpayment is identified to claw back any funds, leaving all parties involved with a very short window to rectify any issues. Since most non-fraudulent improper payments can be attributed to coding issues that could alter the amount of payment – these costs can add up. Consider a little more than 79 percent of all improper payments in the Medicaid system last year were the result of improper documentation.

To resolve the long-term financial impact of improper payments, lawmakers have two potential solutions: placing further preventative controls on payments or improving the improper payment resolution process. Increased requirements could directly reduce improper payments by increasing the amount of information required at the outset of the Medicare and Medicaid claims process, although the corresponding increase in paperwork may increase the administrative burden on providers during the claims process while leading to poorer care outcomes or care denials. As for improving the improper payment resolution process, legislation or new rules may be needed to empower CMS to alter its current claw-back mechanisms or strengthen enforcement mechanisms that already exist. Some argue that improving this process would decrease the number of unresolved improper payments each year, reducing waste in the health care payment system.

As this long debate on improper payments continues, it is imperative that both Congress and CMS work together and plot a path forward to improve program stewardship.

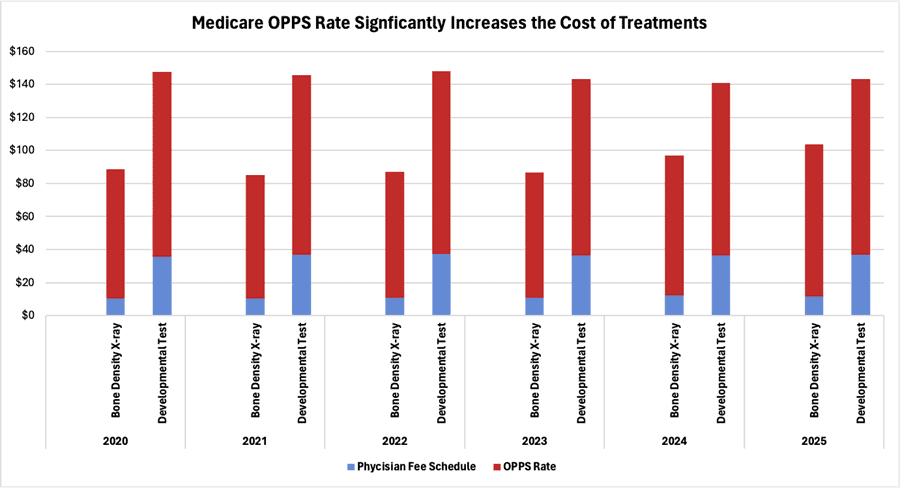

Chart Review: Medicare’s Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System Is Driving Health Care Costs

Nicolas Montenegro, Health Policy Intern

In recent months, bipartisan support has grown in Congress for reforming Medicare payment structures to reduce health care costs. A primary focus is the price disparity between hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) and freestanding physician offices. While both settings generally offer the same quality of care, HOPDs receive an additional payment on the basis that services are provided in a more expensive setting – thereby raising the Medicare reimbursement amount. The additional hospital facility fee can raise the cost of services as much as fivefold, which significantly drives health care spending in Medicare programs.

The chart below illustrates the average Medicare reimbursement for two outpatient treatments. Medicare determines payments made to providers using the physician fee schedule (PFS) – reflecting the agreed-upon cost of the service delivered – in addition to the Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) rate, which incorporates a hospital facility fee. Over the past five years and continuing into 2025, hospitals received an average reimbursement more than 600 percent higher than for physician offices for bone density X-rays. For developmental tests, hospital reimbursements were nearly 200 percent more than physician office payments during the same period. A solution to this trend, as proposed by many health care stakeholders, is the adoption of “site neutral” Medicare reimbursement rates. “Site neutrality” aligns payments for treatments delivered in all settings, meaning HOPDs and physician offices receive the same reimbursement rates from Medicare for the same services. If Congress succeeds in enacting site neutrality provisions for Medicare programs, the Congressional Budget Office estimates that those reforms could save taxpayers more than $100 billion over the next 10 years