Weekly Checkup

April 10, 2020

The Global Drug Supply Chain

At the start of 2020, reducing the prices American patients pay for prescription medications was at the top of the health care priority list for federal policymakers. The coronavirus pandemic sweeping the globe has significantly shuffled the deck on policy priorities. Now, if prescription drugs are on the agenda at all outside of coronavirus-related treatments and vaccinations, it’s in the context of the global supply chain.

It’s ironic that as a result of the pandemic, Congress and the Trump Administration appear more likely to take action actually increasing the costs of pharmaceuticals than bringing them down. There is growing momentum among lawmakers for “Buy American” provisions broadly, and to make changes to the pharmaceutical supply chain specifically in the name of safety, security, and preventing shortages.

One driver of this push is growing discomfort with China. I’m sympathetic to concerns about the threat China poses to America’s national and economic security, but in the case of the pharmaceutical supply chain, our dependence on China may be overstated. Eric Boehm of Reason recently published a good explainer on how we don’t really know how much of the ingredients for our drugs—active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)—actually come from China. We do, however, know that only 13 percent of API manufacturers supplying ingredients for drugs sold in America are based in China. That’s less than the 18 percent based in India, 26 percent in Europe, or the 28 percent based here in the United States. It would be useful to know—and the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act does include provisions aimed at shedding light on—exactly what percentage of the APIs supplied to the U.S. market come from China and elsewhere, but it is apparent now that the global supply chain for U.S. drugs is actually quite diverse.

Of course, for some policymakers the diversity of the supply chain is a problem in and of itself. The “Law of the Instrument” is a familiar concept: When all you have a is a hammer, everything looks like a nail. In the current political context, you can reframe that idea and reverse it: When you believe that globalization is at the root of every problem, then protectionism is your only tool. Back in those halcyon days of late January, when many still believed the coronavirus to be primarily a Chinese problem, Commerce Secretary Wilbur Ross explained that the coronavirus pandemic could have the positive effect of increasing U.S. employment because companies will have to consider the risk of a global supply chain.

We’re all familiar now with the current state of employment in United States. Far from a problem, the diversity of the global supply chain provides some measure of security. Having API suppliers all over the world allows for manufacturers to shift procurement when circumstance require. If the supply chain is more localized, it’s also more likely to be impacted by natural disasters or outbreaks like the coronavirus. Additionally, and here’s the rub, manufacturing APIs overseas is often cheaper, resulting in lower prices in the United States. In 2011, the Food and Drug Administration found that “bulk manufacturing in India can reduce costs for U.S. and European companies by 30% to 40%.” Any move to force pharmaceutical manufactures to shift their supply chains to the U.S. will absolutely lead to increases in the cost of medications for American patients. Further, it takes years and substantial investment to set up manufacturing facilities. Onshoring the U.S. pharmaceutical supply chain wouldn’t be quick, even if it were desirable.

Having a full and data-driven discussion of the safety, security, and sustainability of the pharmaceutical supply chain would be helpful. These issues should be explored, and there is a dearth of useful data. Changes to the existing supply chain, however, must be approached with caution and should not be part of the immediate response to the pandemic. Policymaking in a crisis should be limited to matters directly relevant to and aimed at resolving the immediate challenge. Broad and far reaching policy shifts in a moment of uncertainty and panic are likely to do more harm than good.

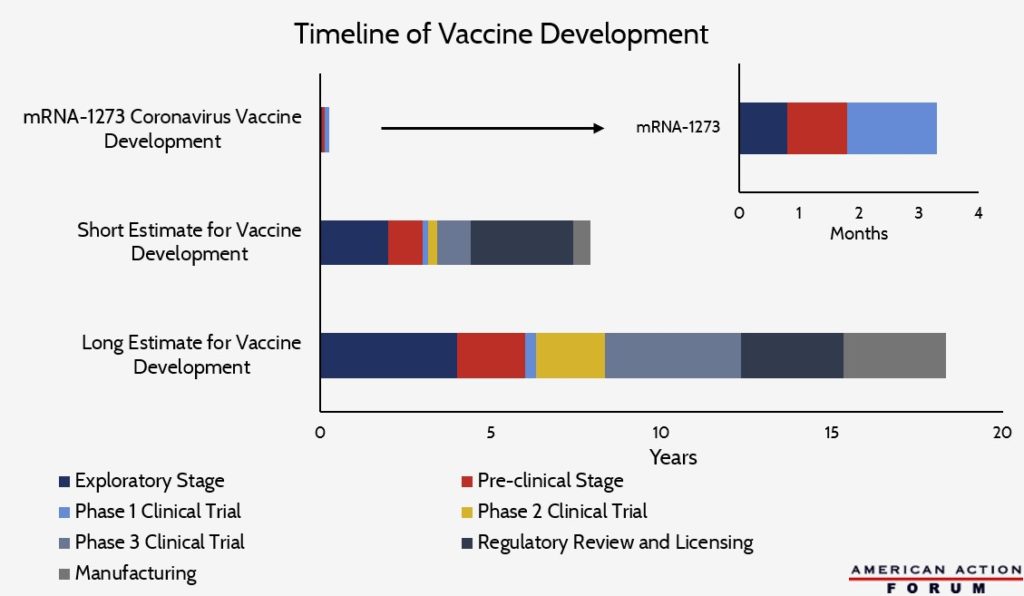

Chart Review: The Pace of Vaccine Development for COVID-19

Josee Farmer, Health Care Policy Intern

The convoluted and complex process of vaccine development – which includes an exploratory stage, pre-clinical stage, three phases of clinical trials, regulatory review and licensing, as well as large-scale manufacturing – can take anywhere from 8 to 18 years, usually falling within the 10 to 15 year range. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, the race to develop a vaccine on a much shorter timeline has become a central goal of drug manufacturers and health experts. While several COVID-19 treatment drugs are already in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials, Moderna’s mRNA-1273 is currently the vaccine furthest in the development process. This vaccine entered phase 1 of clinical testing on March 16th, in which testing on 45 healthy adults began, and phase 2 is expected to begin in a few months, with a significantly larger testing pool. Moderna projects the vaccine will likely become available in 12 to 18 months but may be available for emergency use by the public in Fall 2020. The vaccine mRNA-1273 took roughly two months to arrive at phase 1 of clinical testing, while the typical vaccine development takes 3 to 6 years to arrive at this point.

COVID-19 mRNA-1273 data obtained from Moderna and other vaccine development data obtained from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention link to History of Vaccines, AbbVie, NCBI, and Sanofi

From Team Health

Daily Dish: Recent Trends in Insulin Prices – AAF President Douglas Holtz-Eakin

Rising insulin prices certainly affect diabetics, but the effects are felt more broadly, too.

Taking the Voters’ Pulse on Pharmaceuticals – Douglas Holtz-Eakin

AAF’s recent polling on voters’ attitudes toward various drug-pricing policy proposals provides a valuable guide to an issue that will doubtless re-emerge in the future.

Daily Dish: A Look Back at Pressing Health Policy Issues – Douglas Holtz-Eakin

Voters’ preferred approach to reforming drug pricing is re-designing Medicare Part D to make it more affordable and put downward pressure on prices.

Worth a Look

Kaiser Health News: Newsom’s Ambitious Health Care Agenda Crumbles In A ‘Radically Changed’ World

Health Affairs: Integrating Health And Human Services In California’s Whole Person Care Medicaid 1115 Waiver Demonstration