Weekly Checkup

May 10, 2019

The Importance of Investment Incentives in Drug Pricing Policies

Recently, Bloomberg Businessweek covered the story of Achaogen Inc., a biopharmaceutical company specializing in antibiotics. In the span of less than a year, Achaogen launched its first product, a rare new antibiotic to fight otherwise antibiotic-resistant infections, and then filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy. It’s a striking but, as it turns out, hardly surprising story, and it illustrates the central role of incentives in drug pricing and development.

While the medical community is increasingly concerned about antibiotic resistance and acknowledges the need for new antibiotics, “infectious disease doctors, wary of promoting resistance, are reluctant to use new antibiotics until they’re absolutely needed,” Bloomberg reports. As a result, demand for the drugs is low, and major drug manufacturers are eschewing the antibiotic development in favor of other, more financially sustainable products with better market opportunities.

There is currently a lot of conversation around ideas for incentivizing antibiotic development, but the problem boils down to money. Then-Food and Drug Administrator Scott Gottlieb addressed the problem last year, acknowledging that “a novel antibiotic may have a very limited market. If product developers know that they will not be able to recoup their investments, there may be reduced incentive to invest significant money needed to discover and develop such a drug.” Gottlieb went on to suggest a subscription model not unlike the one being pursued by Louisiana for hepatitis C treatments. But under current market dynamics, new antibiotics don’t generate enough revenue to incentivize their development, even though we need them. The prices paid per dose are too low to be sustainable.

On the other end of the pricing spectrum, this week Novartis made news when they rolled out a potential cure for at least one type of spinal muscular atrophy, an inherited condition that results in death usually before the age of two. A cure for an otherwise-fatal condition would normally be the cause of much celebration, but the pricing dynamics are muting any joy: The patient population for the drug is small—fewer than 500 children are diagnosed each year—and as a result, there are reports that Novartis could set the price of Zolgensma at as much as $2 million for a full course. In an interview with The Wall Street Journal, a spokesperson for America’s Health Insurance Plans said, “A therapy is useless if no one can afford it.”

Other very expensive drugs and treatments are likely to debut in the years ahead. As precision medicine and gene therapies advance, we’re going to see more treatments and cures targeted at ever-smaller patient populations. The development of these treatments is objectively a good thing, but these medications will be increasingly expensive.

My takeaway from these two stories is this: Incentives are a tricky thing. There is widespread belief that pharmaceutical costs are too high. At the same time, prices have to be sufficient to incentivize development. These incentives are about more than just making a profit—relative profit matters, as well. If I can make a bigger return on investment on a new cancer drug than I can on a new antibiotic, why would I manufacture the antibiotic?

Currently policymakers are proposing ways to push down drug prices, such as forced arbitration, direct government negotiation of drug prices, importation of drugs from Canada, and patent reforms. Objectively, pushing down prices also pushes down revenue, which has some corresponding negative impact on innovation. The question is one of degree. Proponents of these ideas believe that prices can be brought down substantially without significant ramifications for innovation. I’m not so sure. Either way, it’s worth keeping in mind investment incentives and honestly confronting the policy tradeoffs.

Chart Review

Kate Dixon, Health Care Policy Intern

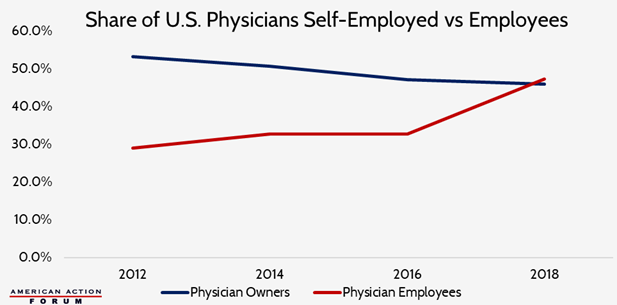

This week, the American Medical Association released an updated report showing that employed physicians now outnumber those who are self-employed. Physician owners now account for 45.9 percent of practicing physicians, down significantly from 75.8 percent in the 1980s. Over a third (34.7 percent) of physicians in 2018 worked either directly in a hospital or in a practice at least partly owned by a hospital. These trends illustrate the consolidation occurring across the entire health care system, partly in response to efforts to decrease cost of care and improve care coordination. Much of the consolidation, however, is also likely due to hospitals’ response to the undesirable financial incentives of many of our federal health care programs, such as the 340B Drug Pricing Program. Many studies show consolidation of close hospital competitors has accounted for price increases of 20 to 30 percent, with some studies indicating increases as high as 65 percent.

Team Health Around Town

Event: The State of Care – Future of Medicare

Deputy Director of Health Care Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes discussed the financial outlook for Medicare at an event hosted by The Atlantic on Wednesday morning, May 8th.

Worth a Look

STAT News: How genetically engineered viruses — and a rotten eggplant — prolonged a teenager’s life

Reuters: Walmart raises U.S. tobacco purchase age to 21 starting in July