Insight

April 13, 2021

Infrastructure, Risk, and Partisanship – Proposed Reform to the National Flood Insurance Program

Executive Summary

- The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is the only broadly purchased flood insurance in the United States, but the program is expensive, cumbersome, and outdated, and owes $20.5 billion to Treasury.

- In April 2021 the Federal Emergency Management Agency announced that it would be updating the NFIP’s risk assessment procedures to bring premiums in line with actual risks posed on an individual home

- House Financial Services Committee Democrats simultaneously recirculated an updated version of the 2019 proposed legislation that had bipartisan support, only this time Democrats included rate hike caps and $20 billion in forgiveness of the NFIP’s debt without consultation with Republican counterparts.

Introduction

The National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) is the principal provider of flood insurance in the United States and plays a crucial role in reducing the financial loss impacts of flooding for over 5 million Americans. Administered by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), the NFIP was originally intended to be the facilitator of a private market of flood insurance and an insurer of last resort, but it has since morphed into the market itself via a burdensome federal program that has cost taxpayers at least $40 billion, is losing $600 million annually, and remains $20.5 billion in debt to the Treasury.

While the program is inefficient and far more expensive than originally intended, structural reform has been difficult to accomplish. Since fiscal year 2017, for example, the program has undergone 16 short-term extensions and brief lapses. Instead of meaningfully reforming the NFIP’s structure, Congress has preferred merely to reauthorize it—an approach that Congress has taken for most of the program’s 50-year history. Only two major reforms have been enacted in total across this period because legislators face an admittedly complicated problem: keeping flood insurance affordable while ensuring the program’s fiscal solvency. Reform is made only more difficult politically as the issue is less one of partisan politics and more a feature of state geography.

Two recent developments for the NFIP strike at the heart of the NFIP’s structural and financial problems. In the first, FEMA has proposed “transformational” changes to the NFIP assessment process, bringing the program into at least the 20th century by using personalized risk assessments to determine individual premium costs, rather than pricing homes en masse on the basis of their location. In the second, House Financial Services Chairwoman Maxine Waters has circulated draft text for a five-year reauthorization bill that would make several program reforms, most notably forgiving an additional $20 billion of the NFIP’s debt. Despite working closely with Republicans on previous NFIP reform initiatives, the proposed bill does not appear to have been produced with Republican consultation, suggesting that Chairwoman Waters is seeking to have the bill included in the $2 trillion American Jobs Plan that the Biden Administration is pursuing.

Context

The NFIP was created by the National Flood Insurance Act of 1968 to address two key policy concerns: first, to minimize the burden on federal disaster relief assistance; and second, to supplement and subsidize a private flood insurance market that otherwise would not be able to provide flood insurance at a cost that homeowners could afford. Despite managing about 5 million flood insurance policies providing $1.3 trillion in coverage over 22,000 communities in in 56 states and jurisdictions, participation in the NFIP is not required by law, but remains nonetheless the only real option available for obtaining flood insurance. By participating in the NFIP program, communities are required to adopt FEMA-mandated floodplain management standards, serving the additional goal of attempting to limit the risk posed by these areas.

FEMA is responsible for performing annual Flood Insurance Studies (FIS). FEMA uses the data generated from these studies to develop and adopt flood maps called Flood Insurance Rate Maps (FIRMs) via its Risk Mapping, Assessment, and Planning (Risk MAP) process. The key element of a FIRM is that it shows areas exposed to at least a 1 percent risk of flooding, which it calls Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs). In calculating the premium a homeowner must pay for their NFIP policy, FEMA classifies properties on the basis of a small number of fairly blunt metrics, including occupancy type and elevation, but the key driver of price is the specific risk zone in which the home can be found on the FIRM.

Although policies are in theory based on a real risk or hypothetical market pricing, this supposed sensitivity is belied by a wide series of carveouts, most obviously grandfathering provisions which allow home rates to stay the same when the risk zone within a FIRM changes. The presence of such carveouts is just one of a number of criticisms levelled at the NFIP, from a small coverage pool, to extremely outdated program technologies, to mapping errors and FIRMs that are only updated every 3-5 years

Risk Rating 2.0

FEMA’s announcement on April 8, 2021, of a new approach to its flood risk pricing methodology, dubbed Risk Rating 2.0, marks the culmination of quiet efforts at FEMA ongoing since 2018. The key element of the project is to tailor FEMA’s Risk MAP process and in particular to assess individual homes on the basis of individual risk, replacing the blunt metric of elevation of homes within a certain flood zone. FEMA will instead consider a wider range of variables, from flood frequency, to type of flood, to distance from water source, and consider homes on a case-by-case basis. Perhaps the most important metric, however, would be the cost to replace. By considering how much it would cost to rebuild individual homes, FEMA hopes to address a longstanding concern that homes of significantly different value with all else being equal pay the same insurance premium, leading to lower-value homes effectively subsidizing the cost to rebuild higher-value homes.

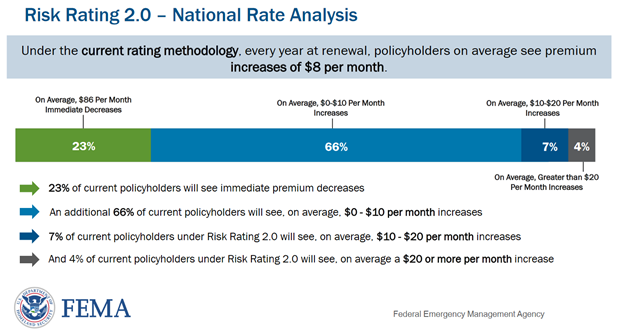

Although there is legitimate concern about the considerable additional costs and experience burden on FEMA to operate the NFIP at this higher level of risk granularity, anything that brings NFIP premiums closer to a true market reality that appropriately reflects risk is to be welcomed and, indeed, is necessary to stop the NFIP from hemorrhaging taxpayer dollars. The necessary corollary of this adjustment, however, is significant premium increases (and, FEMA promises, some decreases) against the backdrop of already-present rate hikes of 11 and 15 percent after April 1, 2020.

Risk Rating 2.0 is scheduled to go into effect for new policies on October 1, 2021, and for renewing policies on April 1, 2022, but the rate increases required have made it difficult for Congress to fully get behind the program, with Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and others urging FEMA to delay implementation of the plan. This reticence is somewhat surprising given the unanimity of climate change activists and insurance analysts on appropriate risk-rated premiums. It makes no sense to expose more capital to sea-level rise or other climate-related damages. Efficient pricing is part of economically rational adaptation, and it also keeps new building and development out of ecologically sensitive areas. Separately, due to the short-term nature of NFIP extensions, the NFIP itself will expire before this point on September 30, 2021; it is highly unlikely Congress would allow the program to expire, however.

A New Congressional Reform Proposal

Meanwhile, House Financial Services Democrats are circulating a draft plan to reform the NFIP and authorize the program for five years. The text is largely the same as a previous bill from the 116th Congress, released in mid-2019 and unanimously approved by Republicans and Democrats in the House committee. That bill focused on the programmatic flaws of the NFIP, in particular related to mapping and information technology, and included among other provisions the appropriation of $500 million for improved mapping technology, a $100 million increase in the mapping budget. As an American Action Forum analysis noted at the time, the glaring omission of that bill was failing to reform policy premiums or address the NFIP’s risk analysis. At first glance, the congressional proposal would therefore seem to dovetail with Risk Rating 2.0 nicely.

Yet two factors threaten this perfect union. First, the new reform proposal contains several new provisions, with two of particular note: a cap on annual rate increases of 9 percent down from 18 percent (seemingly a direct response to Risk Rating 2.0), and the forgiveness of $20 billion of the program’s debt. As noted above, the NFIP owes $20.5 billion to Treasury. All told, the NFIP has borrowed a total of $40 billion, had $16 billion forgiven for claims brought on by Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, and has returned only $2.82 billion of the original principal; this proposal would effectively wipe the NFIP’s remaining debt. Second, the draft plan circulated by House Financial Services Democrats was not produced with any consultation with their Republican counterpart. That House Democrats did not seek the buy-in of House Republicans on these additions suggests that Chairwoman Waters is looking to have the bill text included in the American Jobs Plan, the Biden Administration’s new $2 trillion spending proposal, and bypass congressional Republicans entirely. More information is expected when Chairwoman Waters debuts this NFIP reform bill at a House Financial Services infrastructure hearing on April 14, 2021.

Conclusions

An unusually nonpartisan issue has become unusually partisan. Updating how the NFIP measures and prices risk is vital to modernizing the program and in some way working towards stemming its losses. While the NFIP is expensive, cumbersome, and outdated, by requiring participating communities to abide by floodplain management standards it is an effective tool that the Biden Administration can use to mitigate the risks caused by global warming; the reticence of Democratic leadership in Congress to support the risk update (and particularly one that seeks to more fairly distribute policy costs onto the most expensive homes) therefore rings a bit hollow. Simultaneously, by taking and updating a bipartisan reform initiative unilaterally and attempting to ram it through Congress via the reconciliation process Democrats seek to undo a rare bipartisan policy victory of the previous Congress; it is not clear that the bill’s additions are worth the trouble.