Insight

October 25, 2021

Addressing Oil Prices

Executive Summary

- Over the past year, the global market for oil and gasoline has experienced very rapid shifts in demand paired with slower-moving adjustments in supply; the U.S. market has mirrored this experience.

- As a result, throughout the past year the price of oil has risen over 125 percent domestically and gasoline prices have risen over 50 percent.

- The Biden Administration is reportedly considering a variety of policy changes to reduce prices; none of these policies is either timely or quantitively important enough to have any substantial impact, however.

Introduction

Over the past year, the global market for oil and gasoline has experienced very rapid shifts in demand paired with slower-moving adjustments in supply. During the pandemic-induced downturn, this resulted in oil futures prices briefly dropping into negative territory. More recently, this has produced a rapid rise in oil and gasoline prices.

The U.S. market has mirrored this experience, but on a smaller scale. Thus, while domestic producers have cautiously expanded production, President Biden has called on the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) to increase production and address high prices.

In its attempts to identify how to reduce oil and gasoline prices, the Biden Administration has focused on policies that are either too slow-acting – reversing the moratorium on new oil leases on federal lands – or too small – releasing oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR) – or misguided – banning exports – to be effective.[1]

Shifting Supply and Demand

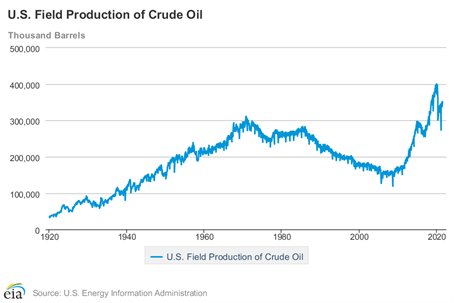

Domestic oil production, mirroring global conditions, peaked in December 2019 and declined in April 2020 in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Since, oil production has begun to recover but has yet to reach 2019 levels. Domestic production in July was 50 million barrels below its 2019 peak as demonstrated in the chart below.[2] Similarly, global production in 2020 declined to 88.391 million barrels per day (mb/d) from 94.961 mb/d in 2019.[3]

In July, OPEC responded to global demand by increasing overall production by 0.4 mb/d as of August 2021. In September, its members failed to meet the quota and OPEC has since decided not to increase production further.[4]

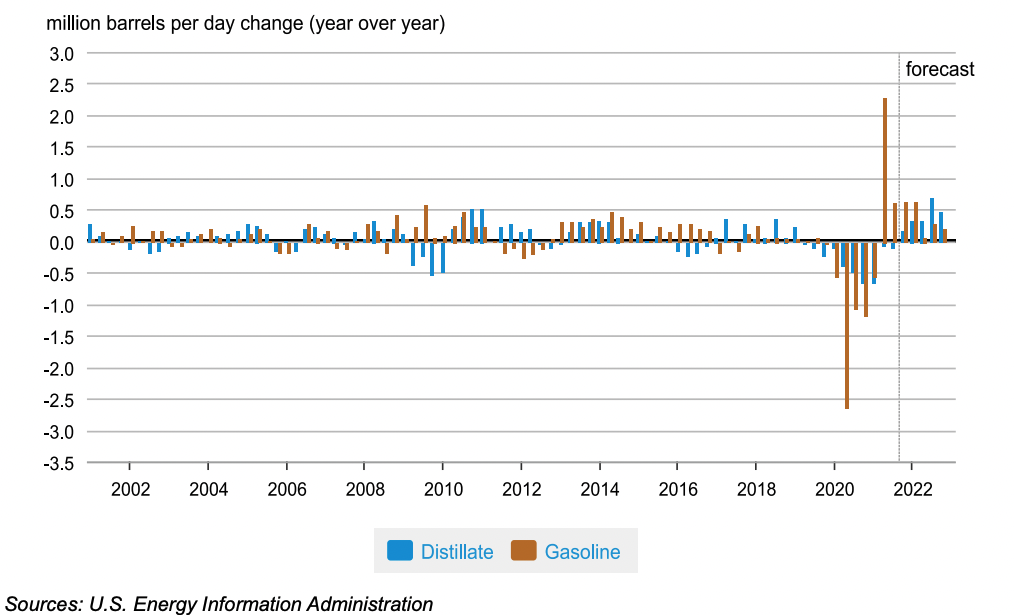

The decline in demand for oil can be attributed to the steep decline in travel associated with the pandemic. As the feedstock for gasoline and jet fuel, among other products, oil was no longer in demand. As the chart below shows, there was also a dramatic decline in refining in 2020 and a rebound in 2021. The demand for oil is projected to reach 2019 levels in 2023 and continue to grow.[5]

Refinery Output

West Texas Intermediate crude oil prices have grown to over $80 per barrel this month, 125 percent higher than in October 2020. And Brent crude, the global oil price, surpassed $80 per barrel as well.[7]

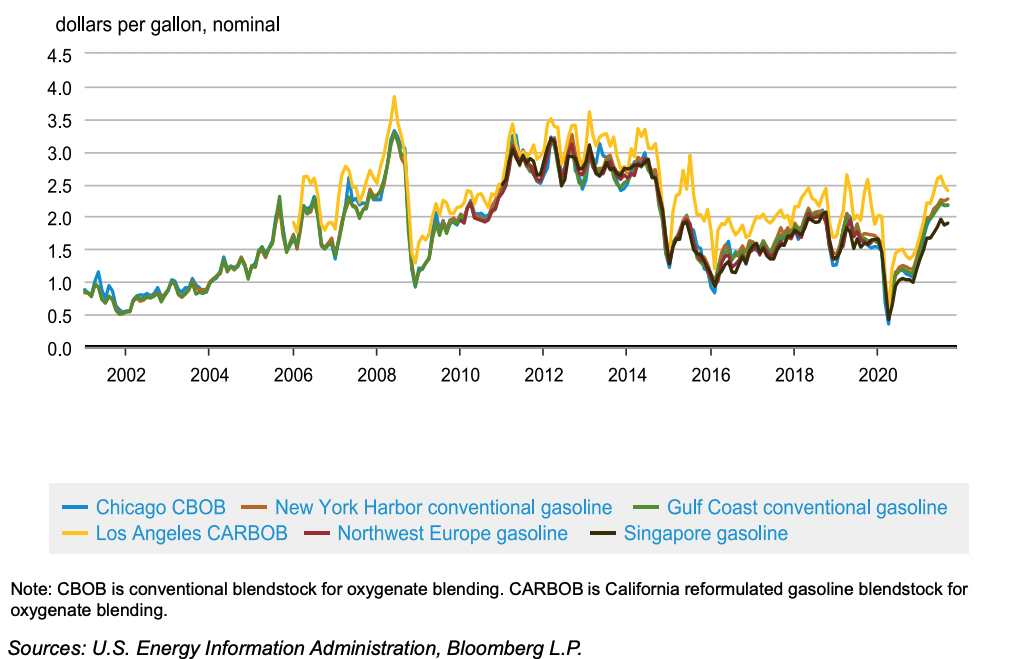

Global Gasoline Spot Prices

Gasoline prices have mirrored global oil prices and are 50 percent higher than one year ago in the United States and abroad (see spot prices below).

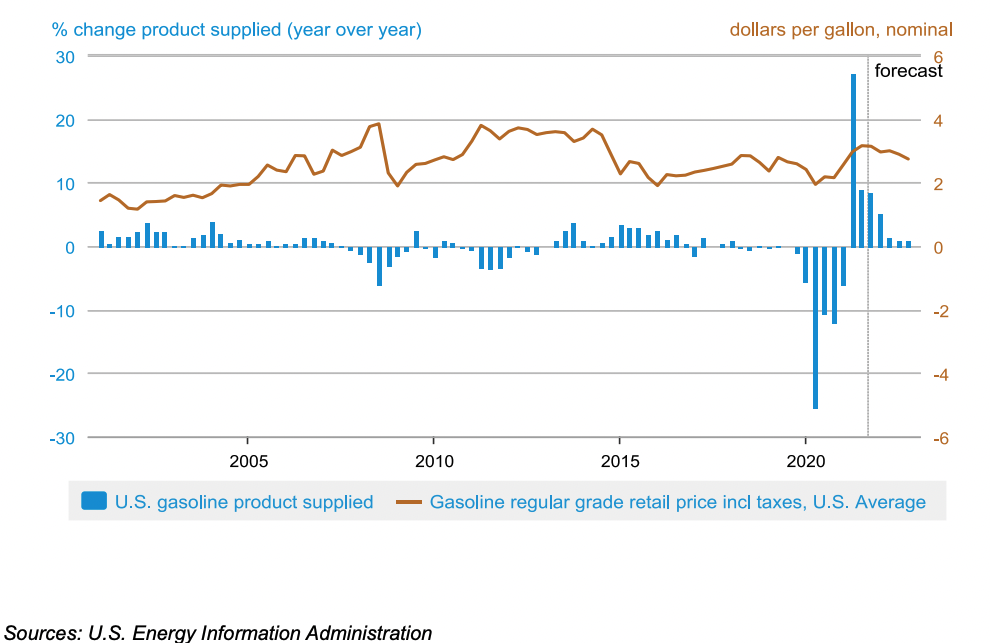

Gasoline consumption increased dramatically in the second quarter of 2021, nearly 30 percent higher than consumption in 2020. Both demand and prices, however, are forecast to decline domestically during the remainder of 2021 and into 2022 according to the Energy Information Administration’s (EIA) petroleum product price formation analysis below.[8] The EIA projects that oil production will increase as additional rigs are brought in service, easing the tension between supply and demand.[9]

U.S. Consumption of Gasoline and Retail Gasoline Prices

While the price of oil is an important factor when considering the cost of gasoline and fuel oils, it is only attributed to about 50 percent of total cost.[10] The price is further impacted by the costs of transportation, location of refining, type of crude oil, and even the season. These factors, in combination with the global nature of the market, complicate the ability to effectively impact prices using only domestic policies.

Potential Policy Solutions

News reports indicate that the Biden Administration has contemplated a variety of policy changes to reduce prices. None, however, is either timely or quantitively important enough to have any substantial impact.

Oil Export Ban

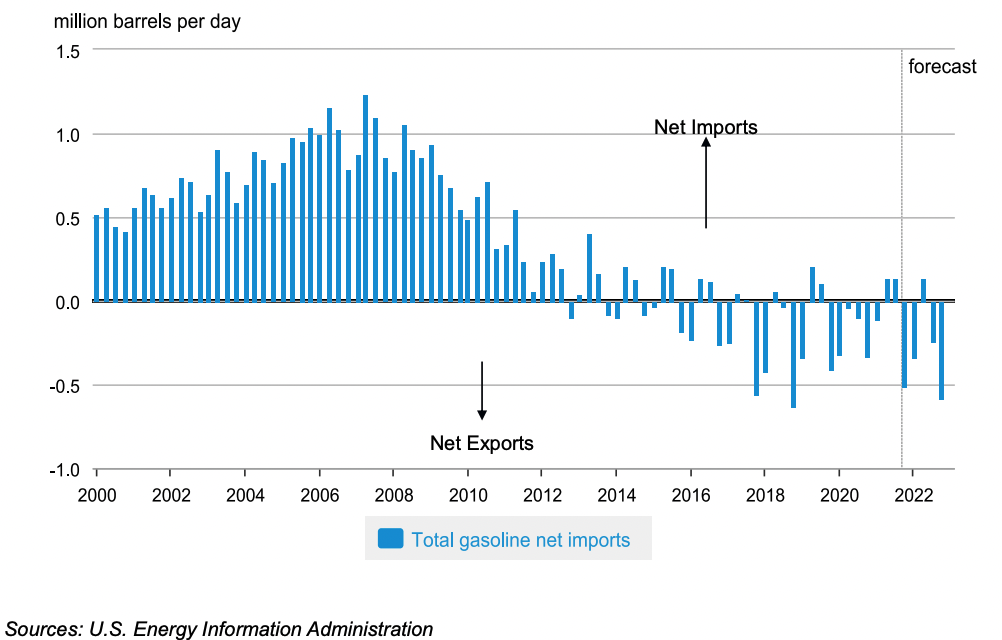

An oil export ban was instituted in the United States in 1975 and lifted in December 2015.[11] Currently, producers and refineries export their products if they can be sold at a higher price abroad. Similarly, refineries will import oil if the feedstock can be purchased for a relatively cheaper price abroad. Throughout 2021, imports and exports have continued as demonstrated in the chart below.

U.S. Total Gasoline Net Imports

According to a Government Accountability Office report, following the institution of the export ban, “From 1975 to 2009, U.S. domestic crude oil production generally declined, and … U.S. imports of crude oil generally increased.” In effect, the ban discouraged domestic production. In turn, it resulted in a more import-dependent economy, the antithesis of the Biden Administration’s goals.

In addition, under an export ban, all oil produced domestically would be refined domestically. Domestic refineries have historically been engineered to process heavier crude oil which is cheaper but requires additional distillation. Oil produced domestically has increasingly been lighter sweet crude better suited for export. Rather than upgrading their facilities and passing the cost to consumers, export allows refineries to produce petroleum products at a lower cost.[12] In addition, constraints are imposed by infrastructure, such as limited pipeline access and the cost of shipping oil in waterborne or rail tankers. The ability to import and export allows refiners to most efficiently use existing infrastructure and reduce costs.

Strategic Petroleum Reserve

The SPR is a series of caverns in Louisiana and Texas where stockpiles of oil are held to counter events that undermine security (for more, see earlier AAF research). Oil is periodically sold from the SPR to raise revenue, as allowed under the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015.[13] Emergency sales may be initiated by the president and conducted within 13 days. Upon the completion of the sale, the physical release of the oil is coordinated; the oil must then be refined so it can enter the market as gasoline. This process can delay consumer access to gasoline.[14]

In addition, the oil quantities sold are typically relatively small. In August 2021, the Department of Energy announced a sale of up to 20 million barrels of oil.[15] This quantity is less than a quarter of one day of global production. With both domestic and global production lacking, sales from the SPR will not be market-moving.

Federal Leasing

Following the issuance of President Biden’s executive order (EO), Tackling the Climate Crisis at Home and Abroad, the Department of Interior halted the leasing of federal lands for the purposes of oil and gas production. Since, the courts have made decisions regarding the validity of pre-existing lease sales as well as the administration’s moratorium.

The United States District Court for the Western District of Louisiana issued a preliminary injunction that enjoins the Department of Interior and its agencies from continuing to “pause” new oil and gas lease sales in offshore waters and on public lands. Louisiana and 13 other states sought the injunction in response to federal government’s actions under EO 14008 which provided that “To the extent consistent with applicable law, the Secretary of the Interior shall pause new oil and natural gas leases on public lands or in offshore waters pending completion of a comprehensive review.” As a result, lease sales will resume in the Gulf of Mexico, with auctions scheduled for November 17.[16]

While no new leases have been sold, the number of permits to drill on leased land has increased. In 2020, 4,226 permits were issued while only 3,181 were issued the prior year. Oil production on federal lands declined in 2020 below 2019 levels but still surpassed production in 2018. Production during the first four months of 2021 was less than during the same period in 2020. In May, however, production rebounded to nearly 2019 levels, about 93 million barrels.[17]

The quantity of production on federal lands is not tied to the number of leases sold nor is the issuance of a permit to drill an indication of intent to produce in the short term. Actions such as issuing additional leases will contribute an insignificant quantity to the supply of oil, at best. Producers often acquire leases for tracts where they do not drill. And any new wells would not immediately be operational. In 2020, the approval of an application to drill was received by the applicant in 142.3 days on average.[18]

Conclusion

With rapidly rising demand for oil and gasoline over the past year, and supply struggling to keep up, oil prices have risen over 125 percent domestically while gasoline prices have risen over 50 percent. While the Biden Administration is reportedly considering a variety of policy changes to reduce prices, none is likely to have a substantial near-term impact—but could have negative consequences in the long term.

[1] https://subscriber.politicopro.com/article/2021/10/white-house-huddles-with-oil-industry-as-gas-prices-climb-2090895

[2] https://www.eia.gov/dnav/pet/pet_crd_crpdn_adc_mbbl_m.htm

[3] https://www.bp.com/en/global/corporate/energy-economics/statistical-review-of-world-energy/oil.html

[4] https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/oil/102521-crude-oil-futures-extend-gains-amid-tight-supply-outlook ; https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/press_room/6512.htm”https://www.opec.org/opec_web/en/press_room/6512.htm

[5] https://iea.blob.core.windows.net/assets/88dec0c7-3a11-4d3b-99dc-8323ebfb388b/WorldEnergyOutlook2021.pdf

[7] https://www.wsj.com/articles/oil-price-jumps-above-80-and-natural-gas-races-higher-turbocharged-by-supply-shortages-11633943832?cx_testId=3&cx_testVariant=cx_2&cx_artPos=1&mod=WTRN#cxrecs_s

[8] https://www.eia.gov/finance/markets/products/reports_presentations/product.pdf

[9] https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/steo/

[10] https://www.eia.gov/petroleum/gasdiesel/

[11] https://www.gao.gov/assets/gao-21-118.pdf

[12] gao.gov/products/gao-21-118

[13] https://www.energy.gov/fecm/articles/doe-plans-sale-crude-oil-strategic-petroleum-reserve

[14] https://www.energy.gov/sites/default/files/2021-06/Strategic%20Petroleum%20Reserve%20%28revised%29_1.pdf

[15] https://www.energy.gov/fecm/articles/doe-announces-notice-sale-crude-oil-strategic-petroleum-reserve-2

[16] https://www.naturalgasintel.com/biden-administration-complies-with-court-schedules-gom-oil-gas-lease-sale-for-november/

[17] https://revenuedata.doi.gov/query-data?dataType=Production#

[18] https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/docs/2021-03/Table12_TimetoCompleteAPD_2020.pdf