Insight

September 12, 2019

Agencies Repeal the Obama WOTUS Rule

The Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the agencies) have finalized the first step of a two-step process to repeal and replace the Obama Administration’s 2015 Waters of the United States (WOTUS) rule. The rule, released Thursday, deals with defining what natural features are considered federal waters under the Clean Water Act. Specifically, the rule repeals the Obama-era rule and restores regulations from the 1980s. In a subsequent final rule, expected by the end of 2019, the agencies will revise the definition of WOTUS yet again. This rule brings regulatory savings but ultimately does little to clarify what counts as a federal water.

THE STATUS QUO

The term’s definition is important because it determines where the federal government can prohibit or require permits for certain discharges or activities, such as land development. While the agencies have issued what they presumed to be clear definitions, courts have struggled to ascertain exactly how far Congress intended to extend the federal government’s reach.

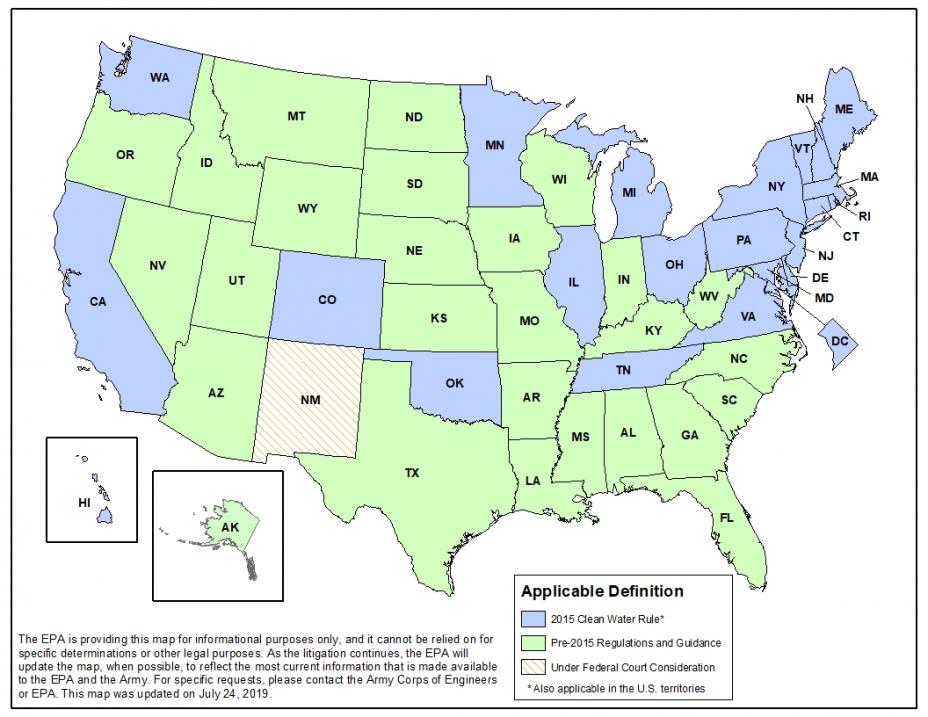

The current state of play regarding WOTUS can be charitably described as muddled. After decades of legal fights, the Obama Administration issued its WOTUS rule to implement a 2006 U.S. Supreme Court decision. This expansive regulatory definition raised many concerns from businesses and landowners. A series of cases around the Obama-era rule and a Trump-era rule to extend that rule’s applicability date has left 22 states technically under the 2015 rule and the remaining, except New Mexico, under the old regulations. The map below from EPA’s website illustrates the current situation.

WHAT THIS WOTUS RULE DOES

The primary accomplishment of this rule is to remove the expansive provisions of the 2015 rule from the regulatory code. A chief concern raised with the 2015 rule was its inclusion of ephemeral, or temporary, features in its definition of federal water. Under the Obama rule, a piece of land with a low-lying feature that fills with water only after heavy rainstorms could have been considered a federal water if it eventually flowed into a navigable water, triggering federal permitting requirements. The inclusion of ephemeral features also greatly expanded the scope of waters subject to the Clean Water Act, generally considered to be navigable waters and waters necessary for commerce. Removing this provision eliminates the uncertainty surrounding ephemeral features.

Second, the rule delivers the Trump Administration total estimated regulatory savings of $1.3 billion. The savings come primarily from compliance expenses that will no longer need to occur.

WHAT THIS WOTUS RULE DOES NOT DO

Unfortunately, the new rule will not provide much clarity. For starters, it restores 1980s regulations that were the subject of litigation that ultimately led to the Obama rule. Second, this new rule will almost certainly be subject to a legal challenge. As a result, resetting the rule to the 1980s’ version continues the uncertainty that has existed since the 2006 Supreme Court decision – with the potential that various federal court rulings could lead to another map like the one above. In addition, it is possible that the rule never takes effect. Should a legal challenge to the Trump rule succeed, it is possible a court will place a nationwide stay on its effectiveness, as occurred with the Obama-era rule. Third, this rule is designed to be replaced by the forthcoming revised definition, so even if it takes effect, it will likely be short lived and could lead to confusion about what definition of WOTUS is technically in effect if violations occur in the interim.

CONCLUSION

The final rule issued by the Trump Administration is a first step toward revising the definition of federal waters, with a second – more important – step expected later this year. It eliminates the expansiveness of the Obama-era WOTUS rule and is estimated to save $1.3 billion in foregone regulatory costs. At the same time, the rule does little to clarify a muddled situation regarding what is, or is not, a federal water.