Insight

March 2, 2022

Assessing State Sports Betting Structures

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The number of states with legalized sports betting continues to grow, with a majority of states enacting enabling laws.

- Because there are no federal laws standardizing sports betting, states are experimenting with a multitude of regime structures and no two states have identical setups.

- While the legalized sports betting industry is still in its early days, initial assessments show benefits to both states and bettors where a competitive marketplace has been established and internet and mobile betting is allowed.

INTRODUCTION

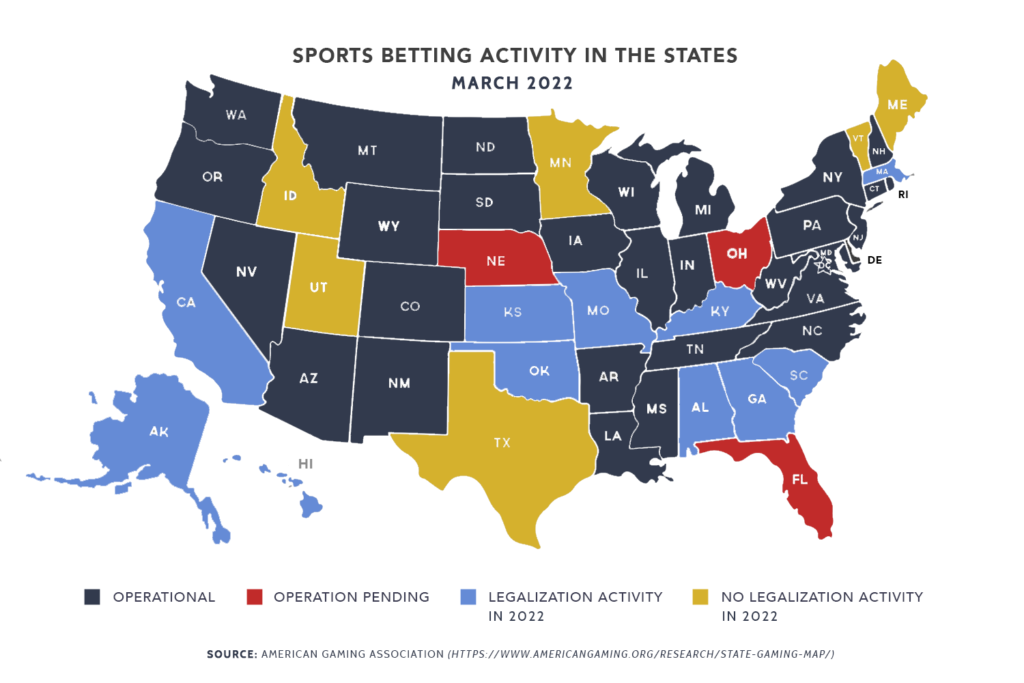

Nearly four years have passed since the U.S. Supreme Court ruling in Murphy v. National Collegiate Athletic Association allowed states to set their own laws regarding sports betting. Today, the majority of states – 33 states and the District of Columbia – have enacted legislation legalizing gambling on sports. Three years ago, when the American Action Forum first examined the legalization of sports betting, just 11 states and D.C. had approved it.

Because states develop their own laws in the absence of federal standards, no two state sports betting regimes are the same. These differences present an opportunity to review which models, and individual components of laws, work better than others. This analysis provides an update on state legalization and assesses what seems to be working – and what does not.

STATE LEGALIZATION ACTIVITY

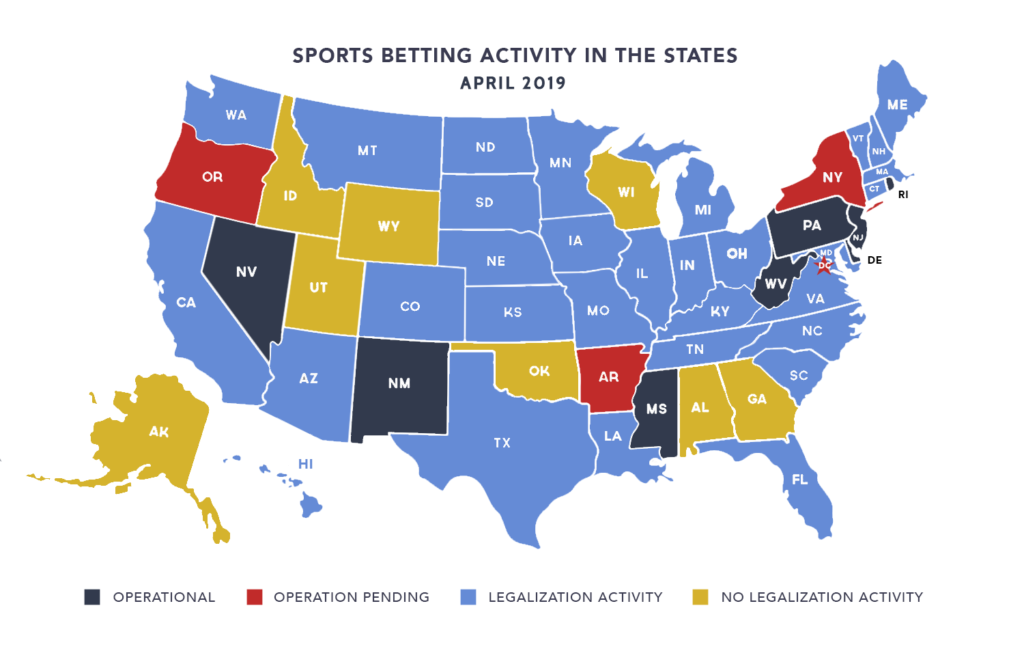

Since the May 2018 Supreme Court decision, two-thirds of the states and D.C. have legalized sports betting in some fashion. Currently, 30 states and D.C. have operational industries, while three more have legalized betting but operations have not yet launched. Several of the remaining states are likely to introduce legislation or consider holding a referendum in 2022. The maps below shows each state’s status compared to April 2019.

The primary allure of sports betting for state governments is tax revenue. According to Legal Sports Report’s revenue tracker, since June 2018 states have reaped more than $1 billion in taxes paid by sportsbooks. Those revenues will surely accelerate as more states legalize and others launch statewide mobile betting via smartphone apps. New York provides an illustrative example of the revenue that can be generated via mobile apps. In January 2022, the first month mobile betting was legal, the state generated $63 million in taxes (mobile betting began January 8). From July 2019 to December 2021 (excluding April through August 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic), when betting was limited to casinos (whose revenue is taxed at a much lower rate than mobile revenues), tax revenue was $4.2 million.

One notable feature of the map above is that the two most populous states, California and Texas, have not legalized sports betting. These states may be motivated by New York’s recent revenues to move toward legalization, although they may also want to see if the revenues are sustainable or outweighed by some of the potential pitfalls of legalized betting, including increased gambling addiction and an oversaturation of advertising. The third most populous state, Florida, has yet to begin operating a sports betting regime as its implementation is blocked by courts. If Florida is allowed to proceed, and if California and Texas decide to legalize sports betting, cumulative state tax revenues will increase significantly.

STATE LEGALIZATION STRUCTURES

States can structure their legal betting industries in several different ways, including limiting betting to physical locations or allowing it statewide via mobile apps, having the industry run by state lotteries (or a contracted monopoly) or fully opening it to competition, and determining how it should be taxed. As such, no two state sports betting regimes are exactly the same. The considerations associated with these options are examined below.

Online and Mobile Betting

Perhaps the most significant component of how a state chooses to legalize sports betting is whether to limit it to physical locations or allow mobile betting. The latter option vastly increases the amount of handle, or the total dollar value of bets placed, in a state. Using data from Legal Sports Report’s revenue tracker, the average monthly handle per capita where mobile betting is available is $44.25, while the comparable average with physical locations only is $3.09. This difference has major implications for sportsbook revenue – the amount of money left over after winning bets are paid out – from which taxes are derived. Average monthly tax revenue per capita where mobile betting takes place is 42 cents, compared to eight cents in states where it does not.[1]

The revenue implications demonstrate why 22 states allow (or will allow) mobile betting, but there are valid reasons to limit it to retail locations. Limiting availability makes it more difficult to place bets, which states may view as a viable way to prevent sizable increases in gambling addiction or reduce the number of bettors that may incur debts.

Monopoly or Competitive Market

For states that allow mobile betting, a second consideration is whether to allow one entity (either the state lottery or a contracted provider) to have a monopoly or allow several sportsbooks to operate in a competitive market. Most states have opted for competitive markets, which have obvious benefits for bettors. Competition forces operators to price their odds lower – or reduce the amount of money that needs to be wagered in order win a set amount in return (typically $100 in American odds pricing) – giving bettors a better chance of winning bets by reducing the percentage of bets they must win to break even. It also leads to better-performing apps and, often, account bonuses designed to entice new customers.

States also seem to benefit from competitive markets, though there are some tradeoffs. Competitive markets lead to a higher handle, which leads to higher tax revenues. A potential downside is that hold percentages – the ratio of sportsbook revenue to handle – tends to be lower since sportsbooks compete on their odds prices and thus win less often. This amount can be more than made up for, however, if the handle is large enough. Essentially, states choosing competitive markets opt for a much broader base so that the volume of bets heavily outweighs the revenue lost from smaller cuts of each wager placed.

Four jurisdictions – D.C., New Hampshire, Oregon, and Rhode Island – have opted for the monopoly mobile betting model, meaning their lotteries administer mobile betting, either directly through their lottery provider or by contracting with a sportsbook operator. The reasons for choosing this option appear to be guaranteed revenue through the awarding of a contract and less nuisance related to the advertising blitzes that take place in competitive markets. For bettors, however, these monopolies are undoubtedly harmful. Absent competition, these operators can price their odds to generate larger holds, which directly leads to more losses for bettors. The apps also tend to be dysfunctional. Oregon’s state-run app was of such poor quality that it has since contracted with a well-known sportsbook to take over, and D.C.’s app has had a run of problems, highlighted by its temporary removal by Apple on all the company’s mobile devices during the recent Super Bowl – famously the largest sports betting day each year – because the developer failed to make a required update.

The obvious risk with the monopoly approach is that bettors get frustrated with heavier losses and poorly performing apps and choose to stop playing or place bets in nearby states with competitive markets.

Tax Structure

Comparing tax structures among the states is more complicated, as there are scores of ways to design regimes. Some states, such as Delaware and Rhode Island, tax revenue at around 50 percent. Others prefer lower rates. Iowa and Nevada, for example, have a 6.75 percent rate. States such as New York, Connecticut, and Louisiana have different rates depending on whether the bet is placed online or at a physical location. Pennsylvania has a 36 percent tax rate on top of a $10 million initial licensing fee. Arkansas taxes the first $150 million in revenue at 13 percent, and anything beyond that at 20 percent.

It is still too soon to know what type of tax structure works best. New York’s recent revenue success due to mobile betting (which is taxed at 51 percent versus 10 percent for land-based revenue) may get other states’ attention, particularly states with larger populations. It is unclear whether its success is sustainable or was the result of the novelty of mobile betting launching and corresponding promotions. As this becomes clearer, it may offer a guide to which tax structures other states choose to adopt.

OUTLOOK

Based on the high rate of states legalizing sports betting, it seems likely that others will follow and learn from earlier adopters’ successes and challenges. Though it is still too early to determine if there is a structure that works best, of the three areas examined above, there appear to be clear benefits to both bettors and states from allowing mobile betting in a competitive market. Bettors have a better chance of winning and can place bets from anywhere – something the pandemic proved can be an obvious benefit. Under this regime, states end up with higher revenues per capita.

Oregon and D.C. offer cautionary tales on establishing lottery-run monopolies on mobile betting. Both states have been plagued by complaints from users about the fairness and performance of their platforms, in addition to opaque contracting processes that have been criticized as enabling cronyism.

One certainty is that federal legislation establishing standards for state betting regimes will not happen anytime soon. While such legislation was introduced in previous Congresses, none has been offered more than a year into the 117th Congress.

CONCLUSION

Today’s level of legalized sports betting in the United States seemed unimaginable a decade ago. More states are likely to legalize the industry in 2022. If those states choose to use the earlier-adopting states as a guide, the best generalized model appears to be allowing mobile betting statewide in a competitive market.

[1] These figures exclude DC, OR, NH, and RI as those state run monopolies do not report monthly tax revenue.