Insight

April 3, 2019

Primer: Sports Betting in the United States

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Since the Supreme Court struck down the federal prohibition of sports betting in May of 2018, 11 states and the District of Columbia have legalized the activity.

- These states have adopted a variety of approaches to authorization, regulation, and taxation.

- The successes and failures of these policies will provide useful examples for the many other states considering legalization of sports betting.

INTRODUCTION

Since a May 2018 U.S. Supreme Court ruling struck down a federal ban on sports betting, several states have moved to legalize the activity within their borders. Proponents promise substantial tax revenues and the benefits to society of legalizing an activity that occurs despite prohibitions. Opponents worry about disproportionate effects on poorer populations and an increase in problematic behavior historically associated with gambling.

This primer looks back at the history of betting legalization in the United States, explores the Supreme Court decision that opened the door for states to legalize the activity, and examines the various approaches states (and the District of Columbia) are taking to set up their regulatory and taxation structures. It also previews what the future holds for other states and the possibility of federal government involvement.

BACKGROUND

Sports betting in the United States has long carried a negative stigma in the eyes of both federal and state legislators along with the high-ranking officials who run professional and collegiate sports leagues. Lawmakers and league executives cracked down on sports betting at the turn of the 20th century. Government officials opposed sports betting in large part due to the rise of organized crime outfits, who used sports bookmaking to fund operations. Those running sports leagues opposed it due to scandals that challenged the integrity of their games—the most infamous being professional baseball’s Black Sox Scandal, in which members of the heavily favored Chicago White Sox were accused of intentionally losing the 1919 World Series to the Cincinnati Reds in exchange for bribes amounting to $10,000 per player.

Betting has been prohibited in all but a few states since 1992, with the enactment of the Professional and Amateur Sports Protection Act (PASPA). PASPA prohibited betting on professional and amateur sporting events, except for certain “pari-mutuel” betting such as horse racing and dog racing. Even among those states where betting was legal (PASPA grandfathered in states that had previously allowed it), only Nevada had traditional full-scale betting with single game wagers allowed on everything from point spreads, score totals, and prop bets.

Despite federal and state bans, betting on sports continued to occur, with the betting ranging from sophisticated (organized crime) to simple (office pools). Some states decided a better approach would be to legalize, tax, and regulate betting, which offers the potential for increased revenue and decreased crime. For these states, overturning PASPA, either in the courts or legislatively, became a priority.

SUPREME COURT OPENS DOOR FOR STATES

In 2011, New Jersey conducted a referendum vote on whether the state should be allowed to amend its constitution to legalize betting on sporting events. The referendum passed 64 percent to 34 percent. The following year the New Jersey Legislature passed the Sports Wagering Act, which permitted sports betting at New Jersey casinos and racetracks. The move was met with backlash as Major League Baseball, the National Basketball Association, the National Football League (NFL), the National Hockey League, National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), and the U.S. Department of Justice all sued the state on the grounds that this newly enacted law violated PASPA. This lawsuit became known as Christie I, named after then New Jersey Governor Chris Christie

Under Christie I, the state of New Jersey acknowledged that its new law violated PASPA, but claimed that PASPA was in violation of the U.S. Constitution’s Tenth Amendment. The state claimed PASPA violated restrictions against the federal commandeering of state governments, which prevents the federal government from forcing state governments to incorporate federal law into their own state law. The U.S. District Court for New Jersey ruled against the state, deciding that PASPA did not violate anti-commandeering laws because PASPA did not issue any affirmative demand forcing states to take new legislative action regarding sports betting, but instead it prohibited states from any authorization of sports betting. The Third Circuit Court of Appeals then backed this ruling in a 2-1 split decision and stated that they did not believe that PASPA prevented New Jersey from repealing its own bans on sports wagering.

Accordingly, New Jersey partially repealed already existing state laws that had placed prohibitions on sports betting, which in turn made the practice legal in the state. The five previously mentioned leagues then sued again claiming a violation of PASPA, which created the lawsuit known as Christie II. The district court again decided against the state, and the circuit court followed with a 2-1 split decision and a 9-3 en banc decision, ruling again that PASPA was not commandeering the state.

In October 2016, New Jersey petitioned for a writ of certiorari from the U.S. Supreme Court. New Jersey made the case that the federal government not allowing it to make modifications to, or specific repeals on its own existing laws was a form of commandeering. The Supreme Court accepted the case, called Murphy v. NCAA (after current Governor Phil Murphy), in June 2017. The Court heard the arguments in December 2017, and issued its decision in May 2018, where it reversed the Third Circuit’s ruling 6-3, with Justice Alito authoring the majority opinion. Justices Roberts, Gorsuch, Kagan, Kennedy, and Thomas sided with Alito in the majority, with Justices Ginsburg, Sotomayor, and Breyer dissenting.

The majority ruling concluded that PASPA was in violation of the anticommandeering doctrine under the 10th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. The majority opinion’s key point was that it did not matter whether the federal government was forcing states to enact new laws or prohibiting them from taking action, as both were forms of commandeering and both essentially tell states what they are and are not allowed to do. PASPA was deemed unconstitutional in this ruling, as it cannot issue direct orders to states in this manner. Justice Alito in his majority opinion wrote “Congress can regulate sports gambling directly, but if it elects not to do so, each state is free to act on its own.”

STATE CONSIDERATIONS

States are primarily motivated to legalize gambling on sports to bolster tax revenues. Nevada first legalized gambling in casinos to increase public funds during the Great Depression, though it initially did not allow betting on sports. The state earned about $17 million from tax revenue generated by gambling on sports in 2017.

Taxes are paid on gross gambling revenue (GGR), which is the revenue left after paying out wins and deducting other eligible expenses. How a state structures its tax rate can have consequences on how much the public will wager. Sportsbooks set betting odds to motivate action and maximize profit. A higher tax rate means a higher percentage of a sportsbook’s revenue is foregone. To make up for this revenue loss, sportsbooks will offer less favorable odds to bettors. Less favorable odds can depress wagering amounts.[1]

States also must consider where and what type of betting will be allowed. Some states limit wagering to casinos, others allow for Internet gambling and mobile betting apps, and some allow betting on apps but not purely on the Internet (as will be explained in more detail below).

Some states have chosen to limit the types of sporting events that can be wagered on. All of the states that have legalized betting have still prohibited betting on amateur athletics, aside from the NCAA and the Olympics. Some have chosen to go a step further to prohibit betting on the state’s own colleges and collegiate events in the state, while one prohibits bets on any of its professional and amateur teams.

It is difficult to know the specific reasons for why a state chooses a certain tax rate and operational setup, or why it limits wagers on certain events. Yet the states are clearly grappling with the traditional moral questions about gambling, the legal consequences of illicit activity like fixing games, and, of course, lobbying by both new and entrenched interests. It is too early in the new world of legalized sports betting to know which mix of approaches works the best, but fortunately states (and the District of Columbia) are choosing a variety of approaches that will make for compelling research over the next several years. Below are brief descriptions of the current configurations in states that have legalized betting and are either now operational or are setting up their regimes.

Operational

Nevada

Nevada legalized sports betting in 1949 as an attempt to thwart organized crime that had overtaken areas of the state, especially Las Vegas, since other forms of gambling were legalized 18 years earlier. The state enjoyed a monopoly on virtually all types of (legal) sports betting until Murphy as a result of its grandfathered status under PASPA and a well-organized state regulatory structure. Despite new competition from other states, Nevada sportsbooks handled more than $5 billion in wagers in 2018, a record amount.

The Nevada Gaming Control Board and the Nevada Gaming Commission administer licenses, issue regulations, and enforce applicable laws. Nevada taxes GGR at a rate of 6.75 percent – the lowest rate of any state. Bettors must be 21 years old to gamble legally. The state allows mobile wagering via apps associated with licensed sportsbooks. To set up an account on an app, however, customers must visit a live sportsbook. Internet sports wagering is not available.

Delaware

Despite New Jersey’s role in allowing states to legalize sports betting, Delaware emerged as the first operational state following the Murphy ruling. The state was grandfathered into PASPA due to a football parlay it once offered through the state’s lottery, which meant no legislation was needed. The state decided to keep the Delaware Lottery in charge of regulating sports betting in 2018, and the minimum age is 21.

Sports betting is split into two types: full-scale wagering on games in the state’s three casinos, and a revived version of the parlay game at sports lottery locations. Mobile wagering has been legalized but is not yet operational. State law does not allow wagers on games involving professional or amateur teams from Delaware. The tax system is a revenue sharing model, with the state taking a 50 percent cut of GGR, casinos getting 40 percent, and the remaining 10 percent diverted to horse racing to supplement purses.

New Jersey

Mere days after Delaware accepted its first legal wager, New Jersey passed legislation allowing sports betting and setting a minimum age of 21. The legislation gave the existing Division of Gaming Enforcement the authority to issue emergency regulations that allowed licensed casinos and race tracks to accept wagers. Rules allowing mobile betting went into effect soon after. In order to be licensed for mobile betting, app providers must be affiliated with a land-based licensee.

New Jersey structured its tax rates differently depending on whether bets are placed via land-based casinos, mobile apps, or at race tracks. Those rates were initially 8.5 percent, 13 percent, and 14.5 percent, respectively. The state recently enacted an additional 1.25 percent levy to fund the state’s Casino Reinvestment Development Authority.

New Jersey prohibits betting on collegiate games taking place in the state or involving New Jersey schools.

Mississippi

Mississippi began accepting bets in August 2018. The state had passed legislation allowing betting in licensed casinos in anticipation of the Murphy ruling, and once the case was decided the existing Mississippi Gaming Commission adopted regulations that are very similar to those of Nevada. As in Nevada, there is no prohibition on wagering on any collegiate event due the schools involved or the location of the game.

Full scale betting is allowed at licensed casinos for individuals 21 and older. Mobile apps are allowed, but only on site at licensed casinos. The tax rate on GGR is at most 12 percent – with 8 percent going to the state and up to 4 percent going to the local government.

West Virginia

In March 2018, West Virginia’s state legislature approved sports betting in anticipation of PASPA being struck down, allowing the state to be operational in August, right before the start of the new National Football League (NFL) season. Full scale wagering is permitted at the state’s five casinos, and bets are allowed for all professional and college sports. The West Virginia Lottery commission oversees and regulates sports gambling in the state. Bettors must be at least 21 years of age to place sports bets in the state. Mobile and online betting is allowed in the state, and the state’s first mobile app was launched in December 2018. Sports betting in the state is taxed at 10 percent on GGR.

Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania passed legislation in October 2017 to legalize sports betting and authorized the Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board to create the regulations needed for the wagering. After the Supreme Court PASPA decision, the law became activated, and the state’s 12 casinos were allowed to apply for sports wagering certificates, but it wasn’t till November 2018 that the first casino debuted sports gambling in the state. The following month two casinos located in two of the state’s major cities, Philadelphia and Pittsburgh, began to offer sports betting. The delay in the launch of sports betting can be attributed to the state’s high costs and regulations, as a casino must pay a one-time $10 million licensing fee and a 36 percent tax rate on GGR. The state now has seven of its casinos offering sports wagering.

The Pennsylvania Gaming Control Board oversees sports betting in the state. Pennsylvania allows full-scale wagering for both professional and college games. Bettors must be at least 21 years of age. Mobile betting is legally allowed in the state, but there have been multiple delays in a mobile rollout. Mobile betting is now expected to launch in the mid-summer of 2019.

Rhode Island

Following the end of PASPA the state legislature passed legislation that officially legalized sports betting in the state. Sports betting in Rhode Island is allowed only at the state’s two casinos, and mobile betting is currently not allowed. You must be at least 18 years of age to place a sports bet. The Rhode Island Lottery oversees the state’s sports betting operations. Full scale wagering is allowed on any professional sports team and any NCAA college sports team except Rhode Island sports teams.

Rhode Island taxes GGR at 51 percent, the highest level of any state that has legalized sports betting.

New Mexico

No sports betting legislation has passed in New Mexico and it remains a fourth-degree felony under state law. But the Tamya Nation that operates a casino on tribal land has circumvented state law due to an Indian gaming compact between the state and the tribe, which authorizes Class III gaming for the tribe on tribal lands. According to the Code of Federal Regulations, sports betting is classified as Class III gaming. The casino began taking its first sports wagers in October 2018.

The Santa Ana Star Casino and Hotel is the only casino in the state currently that permits sports betting. Bettors must be at least 21 years of age. Wagers on professional and college sports teams are allowed, except for local college teams such as the University of New Mexico and New Mexico State University. There is speculation that other tribes in the state could follow in the steps of the Tamya Nation. There are currently 20 other tribal casinos in the state.

Pending Operation

New York

In 2013, New York passed legislation that authorized full-scale sports wagering at four of the state’s casinos, although the law could not be put into effect due to PASPA restrictions. Following the Supreme Court ruling, the legislation was technically able to go into effect, and the New York legislature had a vote on an updated version of the bill. Surprisingly, it failed to pass. Points of contention on the new legislation included expansion of sports betting to mobile platforms and sports leagues’ requests for integrity fees – essentially a cut of betting revenue.

There remain high levels of discussion, and anticipation, around sports betting eventually becoming legal in the state, which will happen once the New York State Gaming Commission (NYSGC) finalizes rules and regulations. After delays, the NYSGC issued official rules and regulations on March 20th, 2019. There is now a 60-day public comment period. The new rules allow full scale wagering at four of the state’s casinos, require being at least 21 years of age to place a sports wager, allow bets on all professional and college sports, do not include integrity fees to sports leagues, and do not allow mobile wagering. The rules will have a chance for modification from the comment period, and then the NYSGC will have to take a vote on the modified rules before official implementation.

The Oneida Indian Nation in upstate New York announced plans in January 2019 to bring betting to three of their tribal casinos and have partnered with Caesars Entertainment in anticipation of the eventual legalization of sports betting in the state. Tribal casinos in New York are legally permitted to allow any forms of gambling and games that are legally allowed in state commercial casinos. The tribe’s plan rests on both approval from the National Indian Gaming Commission, and from the official issuance of sports betting regulations from the state.

Oregon

In 1989, the Oregon lottery created an NFL parlay game, which ultimately made it exempt from the 1992 passage of the PASPA law. This game was discontinued in 2007 due to pressure from the NCAA, which vowed not to allow their championship events in the state. The Oregon Lottery now plans to introduce sports betting games through an Oregon Lottery mobile app, prior to the start of the 2019 NFL season. It is unknown if wagering on collegiate teams will be offered when sports betting reappears in the state due to the state’s history with the NCAA.

Arkansas

The voters of Arkansas approved a referendum in November 2018 to allow betting at four casinos, two of which are already in existence. Of note, it is unclear if one of the two counties scheduled to receive the other casinos actually wants it.

The Arkansas Racing Commission approved regulations in February and set the minimum age for play at 21. Betting is expected to be operational in late spring or early summer. The regulations allow for mobile play. The referendum set a tax rate for casinos at 15 percent on the first $150 million in GGR, and 20 percent thereafter. There is no prohibition on betting on games involving the state’s colleges.

Washington, D.C.

The mayor of Washington, D.C. signed legislation legalizing betting in January 2019. Because the law affects D.C.’s budget, Congress is given a review period and can pass a resolution of disapproval overturning local legislation. The law has yet to go into effect, though Congress is not expected to overturn it. Operation is expected by the fall. Betting is open to anyone 18 and older.

D.C. will take a unique approach. The city will divide brick and mortar locations into two license classes—Class A (the four major sporting venues) and Class B (other retail locations). Class A licensees will enjoy a two-block radius of operating exclusivity. Unlike other some states that have legalized betting apps, D.C. will only have one provider – the contractor that runs D.C.’s lottery (to be renamed the Office of Lottery and Gaming). This option was chosen based on an economic analysis that shows, perhaps dubiously, that a one-operator model will create more revenue for the city since it won’t have to spend time bidding out contracts and letting nearby states potentially get first mover advantage.

OUTLOOK

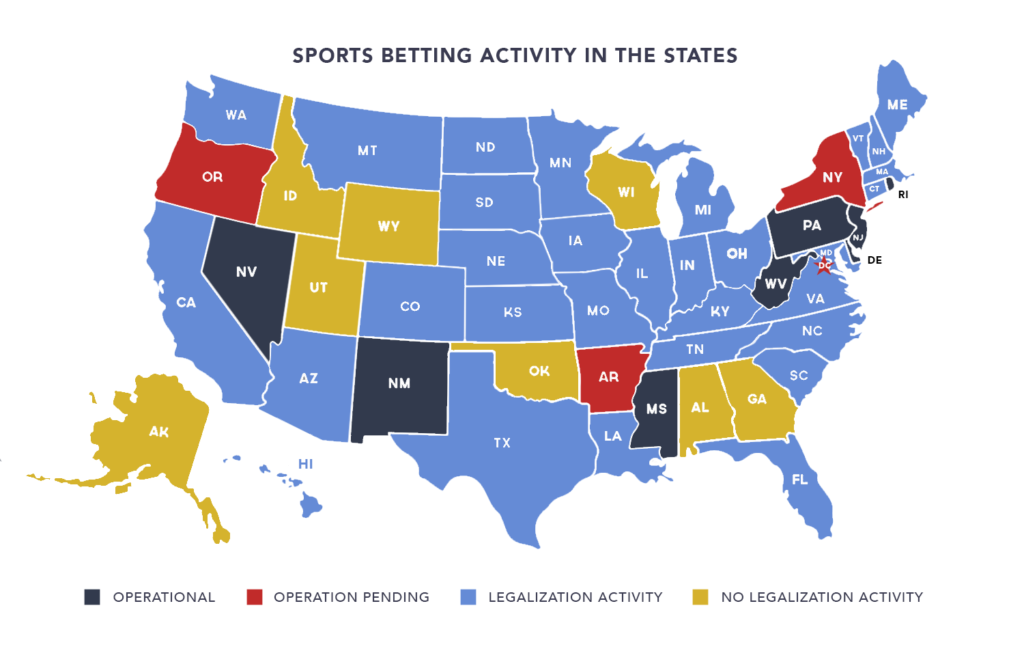

Based on an analysis of activity in every state and Washington, D.C., 31 of the remaining states are actively considering action to legalize sports betting in some form. Just eight appear to have no meaningful activity underway. The map below shows the current status of each jurisdiction in the United States.

The prevalence of legalization activity indicates many states, and perhaps a majority of the 50 states, could have legalized betting in place over the next several years. Polling trends indicate growing public approval of legal sports wagering, although there may be a line drawn when it comes to betting on professional sports versus betting on collegiate. An AP-NORC Center for Public Affairs Research poll released on March 20, 2019, found that 60 percent of those polled around the country would want professional sports betting to be legal in their state, although only 42 percent would want college sports betting to be legalized in their state.

That majority has increased since the Murphy ruling. A Fairleigh Dickinson University poll conducted in May 2018 shortly before the Supreme Court decision found that 50 percent of Americans favored legalized sports betting, with 37 percent opposed. Of the 50 percent in favor, 57 percent of the group believed the practice should be legalized because Americans already do it regardless of its legal status, and 52 percent cited the potential revenue it could bring to the state as a reason. For the 37 percent opposed, 66 percent of that group opposed legalization on concerns it could lead to more Americans developing gambling problems. 62 percent of those polled said that sports leagues should not get any dollars from the revenue created.

The likely increase in the number of states with legalized sports betting will raise the question of whether federal legislation is needed to establish a baseline of certain standards. The Sports Wagering Market Integrity Act of 2018 was a bipartisan bill introduced in the U.S. Senate by Senator Charles Schumer (D-N.Y.) and former Senator Orrin Hatch (R-Utah) in December 2018. Its aim is to set minimum guidelines and requirements for sports betting in the United States. The bill would instruct the Department of Justice to implement these rules. Both senators cited preserving the integrity of sporting contests in the country as their primary goal.

The bill allows betting on professional sports and bans betting on amateur sports with the exception of college sports and the Olympics. The bill also establishes a minimum age requirement of 21 for sports betting. It permits states to authorize online gambling. The legislation also seeks to establish a National Sports Wagering Clearinghouse to analyze sports wagering data in order to detect illegal activity, and to receive and share sports wagering data among sports wagering operators, state regulators, sports organizations, and federal and state law enforcement. It mandates that wagering operators only use data licensed from the official sports leagues. The bill also takes revenue from the current sports wagering excise tax to give to programs related to overcoming gambling addiction. The bill has not been reintroduced in the 116th Congress.

CONCLUSION

Since the Supreme Court struck down federal prohibition of sports betting, 11 states and the District of Columbia have legalized the activity. Legislative activity and polling indicate more states will likely join them, and perhaps in the near future.

As a result of the variety of regulatory and taxation approaches taken by areas where betting is legal, policy makers in other states have a menu of options to consider. These various approaches and impact on government revenues, public behavior, and sporting integrity will affect how many states legalize betting and how soon. They will also factor into whether the federal government eventually gets involved.

[1] Oxford Economics. Economic Impact of Legalized Sports Betting. For the American Gaming Association. May 2017. Page 14.