Insight

September 10, 2018

CRA Poised for Much Needed Refresh

Executive Summary

- The Community Reinvestment Act (CRA), implemented in the 1970s, seeks to prevent discriminatory lending practices to low-income communities.

- The CRA had unusually loosely defined terms when drafted and has not had significant modifications since before the invention of online banking; complying with the Act imposes a large burden on U.S. banks.

- A new proposed rule from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) represents a welcome indication of upcoming reform.

Introduction

As is typical for financial services policy, this story begins with something of an alphabet soup. At the end of August, the Office for the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) released an Advanced Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (ANPR) requesting comment on a proposed update of the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA). So what is the CRA, why is it in need of a fresh glance, and what is the proposal?

What is the CRA?

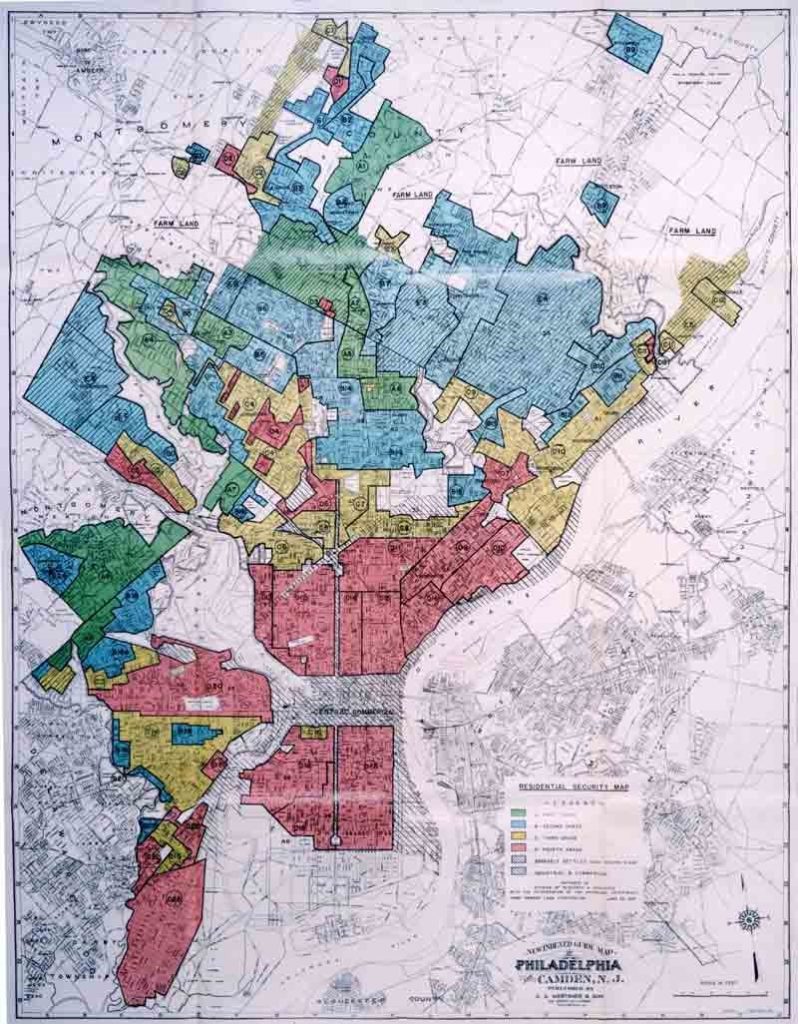

Congress passed the CRA in 1977 to prevent banks from withholding loans or general banking services to individuals from low-income areas, a practice known as “redlining.”

Redlining in Philadelphia in 1937

The CRA requires all banks insured by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) to be assessed to determine whether they offer credit in all communities in which they are chartered to do business. The CRA also specifically sought to avoid risky lending, or lending likely to lead to losses, emphasizing that lending must still occur in a safe and sound manner (for this reason the CRA is not believed to have been a major contributor to the financial crisis).

Banks are assessed by either the Federal Reserve, FDIC, or the OCC. This assessment leads ultimately to a rating and a written report used as part of the supervisory report on the bank. This rating in turn rewards banks with “points,” which allow them to perform certain desirable activities, including issue new charters, open new branches, relocate branches, consolidate, and embark on mergers and acquisitions.

Why does it need to be updated?

Online banking. Drafted prior to the invention of online banking, the CRA is predicated on brick-and-mortar banks serving mappable communities. As originally drafted, the CRA did not even account for interstate banking (illegal at the time). As banks increase the range of Internet banking services, the CRA is looking increasingly redundant – and that redundancy actually harms some banks, such as Ally, that operate only online; Ally receives no credit at all for fair lending in Detroit, where it is headquartered. Besides not giving banks the credit or rating they deserve, this faulty definition of assessment area may compel banks to cut their services to certain communities since they know it won’t make a difference under examination for CRA compliance.

CRA regulators don’t look at the percentage of loans made by a bank granted to low/middle-income customers, but rather at the raw numbers – how many and what amount. This metric essentially moves the goalposts for banks based on their size, as it’s nearly impossible to compare a global bank to a community bank in regard to the number and dollar value of loans they originate.

The assessment mechanism is also curiously poorly defined. Based on interviews and no discernable metrics, banks’ ratings, for all they know, may be based on divination by entrail or ailuromancy. Even the ratings themselves (“excellent,” “substantial”) are undefined. The assessment process itself is costly and time consuming.

There is even a question of basic effectiveness. A study performed by the Competitive Enterprise Institute in 2008 did not find any direct evidence of improved lending in low-income communities.

What is in the proposal?

Although the proposal offers little in the way of concrete suggestion, the questions posed are illuminating. Key among them are questions relating to the introduction of a metric-based assessment – which could be as simple as a ratio of a bank’s size to its fair-lending activity. Switching to a metric-based rating system that instead looks at a ratio adds the nuance needed to rate banks properly and see how they stack up against one another.

Such a measure would vastly decrease the compliance burden on banks and help combat accusations that the CRA is based in political sentiment rather than measurable regulation. Similarly, a streamlined assessment process would cut down on the time and cost involved.

Next Steps

The OCC under Comptroller Otting continues a bullish approach to reform. It is unusual, if not unprecedented, for an ANPR to be issued by only one of the related agencies – it remains to be seen if FDIC and the Fed will expressly endorse the OCC’s ANPR. The OCC has form in this area; it likewise was the first and only agency out of five to begin soliciting comment on Volcker 2.0 in September 2017. Although moving alone raises questions of redundancy, disagreement, and lack of coordination amongst the agencies, Otting has demonstrated an impressive zeal to comply with banking deregulation as mandated by the Mnuchin Treasury.

Conclusions

“Stakeholders of all kinds have spoken up, calling the current regulatory framework for the CRA outdated, complex, and cumbersome,” Comptroller Otting said upon the release of the ANPR. The OCC proposal is a much-needed indicator of sensible reform and relief for U.S. lenders. The CRA must be modernized if it is to be of any value to anyone, particularly to those from low-income communities; deregulation to reduce unnecessary compliance burdens is always welcome.