Insight

July 17, 2019

Estimating the Effect of Small Business Panel Reform

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Small Business Advocacy Review (SBAR) panels have proven effective at reducing regulatory compliance costs for small businesses, but only three federal agencies are required to use them.

- Legislation to expand the SBAR process to other agencies that often issue rules affecting small businesses will be considered later this month; past attempts have been derailed due to concerns that too many panels would strain the affected agencies.

- This analysis estimates that the proposed reform would yield as many as 27 new panels, which would provide meaningful review of a selection of rules; it does not anticipate it would overwhelm the agencies involved.

INTRODUCTION

The 116th Congress has been bereft of action on regulatory reform efforts. The Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, however, is expected to mark up a bill soon to reauthorize the Small Business Administration (SBA) including draft language that promises to give small businesses a stronger voice on rules that directly affect them.

The draft language would increase the number of agencies that would be required to hold Small Business Advocacy Review (SBAR) panels, sometimes called small business panels, on rules that significantly affect small businesses. While this reform is deep in the regulatory weeds, it is likely to improve several regulations without straining the capacity of federal agencies.

BACKGROUND

Today, small businesses account for 99.9 percent of all United States businesses and employ over 47.5 percent of the U.S. workforce. Despite the vital importance of small businesses to the U.S. economy, federal laws and regulations have often disproportionately burdened them relative to large firms, leaving many small businesses struggling to survive. A working paper published by the Mercatus Center estimated that a 10 percent increase in regulatory restrictions on an industry resulted in a .5 percent reduction in the number of firms. A 10 percent reduction in regulatory restrictions had no significant impact on larger firms, however. Accordingly, small businesses are disproportionality affected by regulation.

To help reduce the relatively heavy burden of federal regulations on small businesses, Congress passed the Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA) in 1980 and an amending law, the Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act (SBREFA) in 1996. Both laws aimed to improve regulation and promote competition by ensuring agencies consider the impact of their rules on small businesses. These efforts have shown promise, with the federal government estimating it has saved small entities more than $130 billion in regulatory costs since 1998. Today, the RFA and SBREFA give small businesses a voice to advocate for flexible regulation that does not place an unnecessary burden on small businesses.

The RFA requires federal agencies, before they propose and finalize a rule, to conduct regulatory impact analyses on all regulations that affect small businesses and other small entities. The RFA does not mandate that federal agencies adopt regulations that are beneficial to small business. Instead, it aims to ensure that agencies consider the specific circumstances of small businesses and limit undue regulatory burden whenever possible.

SBREFA amended the RFA by providing for direct input by small businesses and industry stakeholders during the rulemaking process. One particular way SBREFA strengthened the RFA is by mandating that specific federal agencies — originally the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), and later the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) — conduct SBAR panels before proposing any rule that would have a significant economic impact on a substantial number of small entities. These panels are comprised of federal employees from the specified agencies, the Office of Advocacy (an independent agency at SBA), and the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs. The panels interact directly with small businesses owners and other stakeholders before rules are proposed with the goal of increasing efficiency and minimizing burden. History shows that the panels can be effective at allowing agencies to meet their objectives while reducing direct compliance impacts on small businesses.

For example, in FY 2007 the EPA convened an SBAR panel to discuss a proposed rule to increase air pollution standards for small gasoline-powered engines and equipment. Due to concerns that the rule would place a greater burden on small businesses, the panel recommended the compliance deadline be extended and suggested ways to streamline the certification requirements and hardship exemptions for small businesses. The EPA incorporated these recommendations, saving small businesses $36.4 million in first-year costs and $5.6 million in annual recurring costs. Similarly, in FY 2015 the Obama Administration finalized OSHA’s Confined Spaces in Construction rule with significant input from a related SBAR panel. OSHA streamlined the definitions of confined spaces, resulting in savings of $8.2 million in annual regulatory costs for small businesses.

POSSIBLE EXPANSION OF SBAR PANELS

Given the relative success of the SBAR panel process in improving regulatory outcomes and reducing compliance costs for small firms, it is no surprise that many have called for expanding the requirement to other agencies. Draft language included in the SBA Reauthorization would expand coverage to the Department of the Interior (DOI), the Department of Labor (DOL), the Internal Revenue Service (IRS), the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), and the SBA. These agencies often issue regulations that could be considered unduly burdensome on small businesses.

Previous efforts to add agencies to the SBAR panel process have failed for a variety of reasons. One reason for these failures is that expanded coverage to additional agencies has previously been coupled with broadening the definition of “impact.” Currently, impact is defined as costs imposed on small businesses directly regulated by a rule. For example, a small business required by the EPA to report chemical usage would be considered directly regulated.

Past reform attempts have sought to broaden this definition to “reasonably foreseeable indirect” impacts, such as a rule that would tighten regulations on power plants and result in an increase in the cost of electricity on end users, like small businesses. While this idea has merit, it also increases the number rules that would be subject to panels. Some have contended this would make the SBAR panel process unsustainable, since it would surpass the capacity of the Office of Advocacy in both cost and manpower. It is not possible to estimate the number of panels that would be required under this expanded definition, since agencies currently do not estimate indirect economic effects.

The draft language in the SBA Reauthorization legislation leaves the current definition of “impact” intact, making it possible to estimate the effect of the proposed SBAR process on agencies. This study calculates this estimate below.

ESTIMATED PANELS AND IMPLICATIONS

Using data from the Spring 2019 Unified Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions, this study estimates the number of panels that would be expected from the current slate of rules is as many as 38 of the 754 active rules in the pipeline at these agencies. To arrive at this estimate, this study selected current actions in the Prerule (initial development) or Proposed Rule stage that were tagged as either “small businesses affected” or “Regulatory Flexibility Analysis Required.” Only actions marked as either “regulatory” or “other” under Executive Order 13,771 were included since deregulatory and insignificant actions have not triggered the SBAR panel requirement under the Trump Administration.

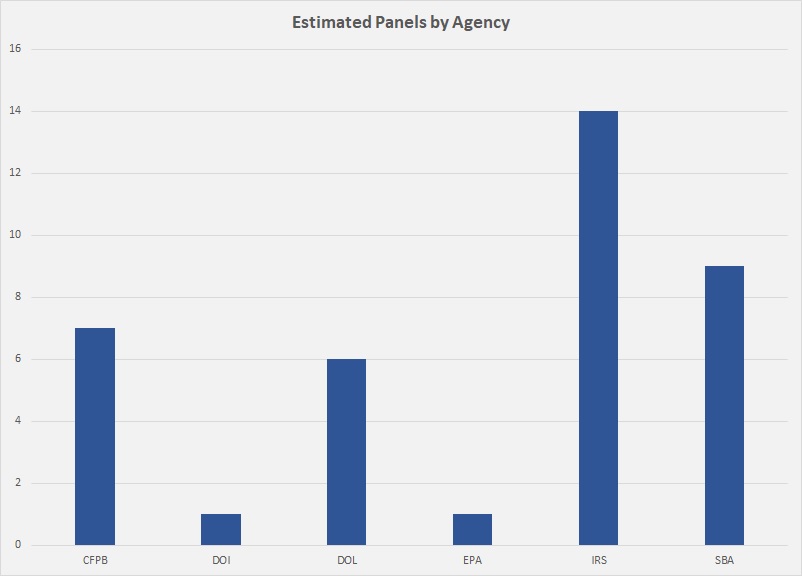

The chart below breaks down these panels among the relevant agencies. Of these 38 panels, 11 are from rules that would be covered under existing law (seven from CFPB, three from DOL [OSHA] and one from EPA). That leaves 27 newly covered rules, should the proposed reforms get enacted. (None of the rules in FDIC’s most recent regulatory agenda would qualify.)

It is possible that this estimate is higher than the true number of panels that would be convened under the proposed reforms. All 14 of the IRS’s rules are marked as affecting small businesses, but not marked as requiring a regulatory flexibility analysis, meaning that the agency thinks small businesses will be affected, but perhaps not at a level that requires an SBAR panel. Therefore, none, all, or some of the 14 could result in a panel. In contrast, all nine of SBA’s rules are marked as requiring a regulatory flexibility analysis, meaning the agency would be expected to convene panels for those rules.

Aside from the questions surrounding the IRS, the implications of this reform appear to be modest in an administration that is less regulatory than its predecessors. There would be more panels — meaning those rules should be improved — but not so many more that agencies, especially the Office of Advocacy, would be overwhelmed. It is important to point out that since many of these rules often take several years in development, these panels would occur over years, not immediately. For context, during the full 16 years of the George W. Bush and Obama Administrations, EPA completed 24 SBAR panels and OSHA completed 9. The CFPB has completed five since it began convening panels in 2012. Assuming the covered IRS rules ultimately shake out somewhere in the center of its 0-14 range, none of the newly covered agencies appear to be significant outliers from the history of previously covered agencies.

This estimate is based on current regulatory activity, it should be noted, which could skew the results somewhat. Expanding the SBAR panel process would likely have a greater effect in a more traditionally regulatory administration. Because such an administration would propose more regulatory actions, we could expect to see more panels than we have estimated here. The panel process should improve those regulations in terms of their efficiency, however, by achieving the agencies’ desired goals while minimizing the impact on small businesses to the extent possible.

CONCLUSION

Improving the RFA by expanding the SBAR panel process to more agencies makes sense. Panels have proven effective at reducing compliance costs for small businesses — an important outcome, since small businesses are disproportionately affected by regulations. The proposed reform in the SBA Reauthorization would expand coverage to a limited number of agencies that most often propose rules that affect small businesses. Accordingly, one should anticipate a meaningful, but measured increase in regulations going through the panel process.