Insight

July 7, 2025

Evaluating the OBBBA’s Energy Provisions

Executive Summary

- The One Big Beautiful Bill Act (OBBBA), signed into law on July 4, includes provisions to overhaul the clean energy credits included in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA); these provisions are estimated to raise approximately $499 billion in net revenue from 2025–2034.

- Among these eliminated energy credits are the clean vehicle credits, residential clean energy and energy efficiency credits, clean hydrogen production credit, and a phaseout of other credits including the clean electricity production and investment credits, which together are estimated to raise about $543 billion from 2025–2034.

- The legislation also expands some energy provisions such as the clean fuel production credit and advanced manufacturing credit, which are estimated to cost about $44 billion over the same period.

- Overall, the OBBBA’s energy provisions do not make much progress in conforming the IRA’s energy credits to the good-tax-policy principles of simplicity, efficiency, and fiscal sustainability, and while some of the provisions greatly enhance the simplicity and efficiency of the energy credits and raise some revenue, others make the credits much more complex and inefficient.

Introduction

The One Big Beautiful Act (OBBBA), signed into law on July 4, 2025, includes extensive energy provisions to overhaul the clean energy credits included in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which are estimated to raise approximately $499 billion in net revenue from 2025–2034.

The legislation will eliminate numerous energy credits including all the clean vehicle credits, residential clean energy and energy efficiency credits, and clean hydrogen production credit by the end of 2027, and other credits several years later, with various phaseout schedules. Together, these provisions are estimated to raise about $543 billion from 2025–2034.

The legislation also expands some energy provisions such as clean fuel production credit and advanced manufacturing credit, which are estimated to cost about $44 billion over the same period.

Overall, the OBBBA’s energy provisions do not make much progress in conforming the IRA’s energy credits to the good-tax-policy principles of simplicity, efficiency, and fiscal sustainability. See a previous American Action Forum (AAF) paper for a detailed analysis of the energy credits and an evaluation of them against the principles of simplicity, efficiency, and fiscal sustainability.

The OBBBA’s energy provisions include simplicity and efficiency enhancing provisions such as those that eliminate the poorly designed clean vehicle credits, standardize credit rates for different qualified energy technologies or components, and retain the refundability and transferability features. The legislation also contains complex and inefficient provisions that restrict taxpayers’ full access to the credits, such as expanding the foreign entity of concern (FEOC) rules and using an arbitrary approach to pick winners and losers across various energy technologies.

This paper provides an overview of the legislation’s changes to the IRA energy provisions and evaluates the energy provisions against three good-tax-policy principles of simplicity, efficiency, and fiscal sustainability.

Summary of the OBBBA’s Changes to the IRA Energy Provisions

The OBBBA overhauls the IRA energy provisions in the following areas. (See detailed information on expiration dates, exceptions, and special rules in the table in appendix.)

- Eliminates some credits: The legislation repeals all the new, used, and commercial clean vehicle credits, alternative fuel vehicle refueling property credit, residential clean energy and energy efficiency credits as soon as after September 30, 2025, with some of them expiring after June 30, 2026. It also repeals the clean hydrogen production credit after 2027.

- Brings expiration dates forward: The legislation brings forward most of the expiration dates for wind and solar in the clean electricity production credit, clean electricity investment credit, and advanced manufacturing production credit to December 31, 2027. It also makes the permanent advanced manufacturing production credit for critical minerals temporary, starting its phaseout in 2031 and fully eliminated four years later.

- Strengthens foreign entity of concern restrictions: The legislation significantly expands the foreign entity of concern (FEOC) provisions by prohibiting taxpayers from getting “material assistance” from a “prohibited foreign entity,” which includes a “specified foreign entity” or a “foreign-controlled entity.” The FEOC provisions also include specific restrictions regarding a “foreign-influenced entity.”

- Removes emissions-related targets: The legislation eliminates the emissions-related conditions that determine the expiration dates for clean electricity production and clean electricity investment credits. Instead, both credits start to phase out in 2034 and are repealed fully by 2036.

- Expands the scope of certain credits: The legislation expands some energy credits, including by extending the clean fuel production credit from 2027 to 2029, adding a new production credit for metallurgical coal equal to 2.5 percent of production costs, and adding a new energy community bonus credit of 10 percent to the clean electricity production credit for advanced nuclear facilities.

- Makes limited changes to some credits: The legislation retains the energy credits for carbon oxide sequestration and nuclear power production mostly as detailed in the IRA and adds only FEOC restrictions to them.

- Retains transferability, refundability, and most bonus credits: The legislation retains transferability and refundability for the credits and other special bonus credit requirements including domestic content rules, prevailing wage bonus, and apprenticeship bonus.

Evaluating the OBBBA’s Energy Provisions

Simplicity, Efficiency, and Fiscal Sustainability

The IRA uses tax subsidies to encourage the production of clean energy. Although the income tax is not the best approach to addressing climate change, energy tax credits should follow the principles of good tax policy. Ideally, tax policies should be simple, efficient, and fiscally sustainable. This allows the federal government to incentivize clean energy development without imposing unnecessary burdens on taxpayers and the economy. A previous American Action Forum (AAF) paper on the IRA energy provisions provides a detailed analysis of the credits and uses a framework of simplicity, efficiency, and fiscal sustainability to evaluate them. The three principles are defined as follows:

A simple tax credit is one that makes it easy for the government to implement clean energy tax incentives and the taxpayers to utilize them, keeping both administrative and compliance costs low.

An efficient tax credit would ensure that eligible taxpayers can utilize clean energy tax credits as much as possible to help drive the economy’s transition to clean energy technologies. It should also limit the extent to which the tax incentives distort producers and consumer behaviors in ways that impose additional costs. It is worth noting that there is a tension between efficiency of clean energy tax credits and the conventional meaning of tax efficiency, as clean energy tax credits are designed to change taxpayers’ behaviors and encourage them to switch to the consumption of clean energy technologies.

A fiscally sustainable tax credit is one that limits budgetary costs and can ultimately be financed through a low level of taxation.

Simplicity

The IRA’s tax credits were designed with excessive complexity. Many of the energy tax credits have multiple requirements that significantly limit eligible taxpayers to a specific group of businesses or individuals, which requires regulators to allocate more resources to screen and verify eligibility and taxpayers to incur a larger burden to comply with the requirements.

Tax credits can be simple to administer and utilize if they have universal provisions. If they are designed to subsidize certain taxpayers or economic activities, however, the complex eligibility requirements could substantially increase administrative and compliance costs.

The OBBBA significantly simplifies the design of the energy provisions by eliminating the poorly designed clean vehicle tax credits. AAF’s analysis finds that the clean vehicle credits’ onerous eligibility requirements, income thresholds, and bonus credit rules make them complicated for regulators to implement and difficult for taxpayers to claim the full credits. Indeed, AAF concluded in its previous analysis that the clean vehicle credits fail against all three principles, as they are complex, inefficient, and costly.

Additionally, the OBBBA surgically improves the simplicity of some energy provisions by standardizing credit rates for different qualified energy technologies or components. For example, for the clean fuel production credit, the legislation reduces the credit rate for sustainable aviation fuel to conform to the rate applicable to other eligible transportation fuels. For the advanced manufacturing production credit, the legislation eliminates the permanent feature of the critical minerals credit and changes it to the same expiration and phaseout schedule as most other eligible components.

The OBBBA adds restrictions and requirements to the energy credits, however, making them more complex to claim than necessary. A striking example is that the legislation expands the IRA’s FEOC restrictions significantly to prohibit eligible taxpayers from being directly or indirectly associated with any specified or defined foreign entity of concern. The new FEOC provisions apply restrictions in several ways. A prohibited foreign entity cannot claim the credit. Eligible taxpayers cannot source their input materials from a specified foreign entity or a foreign-influenced entity. Additionally, eligible taxpayers cannot enter into a licensing agreement with a prohibited foreign entity. The legislation also adds a new 10-year recapture special rule to the FEOC restrictions. For example, for the clean electricity investment credit, eligible taxpayers are prohibited from transferring payments to a specified foreign entity over a 10-year retroactive period. This rule goes into effect in the tax years beginning two years after the enactment of the OBBBA. The new FEOC restrictions substantially increase the complexity of implementing, interpreting, and utilizing the credits.

The OBBBA retains some of the complex special rules in the IRA, including the domestic content rule and prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements. For example, for the clean electricity investment credit, the OBBBA modified the domestic content rule to make it harder for taxpayers to claim the credit by increasing the percentage of eligible products that must be produced in the United States. This requirement may be challenging to comply with as the United States has been relying on certain imported goods as components for energy products and it is more costly to produce them domestically.

Efficiency

The IRA clean energy credits have a combination of features that make them efficient in some ways and less inefficient in others.

The OBBBA retains the efficiency-enhancing features of refundability and transferability. These provisions allow taxpayers to fully utilize the credits for which they are eligible. For example, a startup carbon capture technology company is not typically profitable in its first few years of business, which means that it does not have any taxable income or tax liability, so it cannot use any standard tax credits to reduce its tax liability. With refundability and transferability, the company can either get a refund (a direct payment) from the government as if it had a tax liability or sell the tax credit to another business for cash. Retaining the transferability feature applies to one of the good-tax-policy principles of efficiency, but the OBBBA adds significant FEOC restrictions to prohibit businesses from transferring credits to a specified foreign entity, which reduces the efficiency of the credits and limits taxpayers’ access to claim the credits.

As discussed above, the legislation greatly improves the efficiency of the energy provisions by repealing the inefficient clean vehicle credits. These credits subsidize consumers who would have bought a clean vehicle anyway, and do not incentivize consumers to use electricity generated with clean energy for their vehicles.

In contrast, OBBBA’s arbitrary approach to different types of energy technologies reduces their efficiency considerably. Overall, the legislation favors baseload energy (capable of running continuously), such as nuclear, geothermal, and hydropower, over other intermittent energy sources, including wind and solar. For example, the clean electricity production and investment credits will expire for wind and solar much sooner than for other types of clean energy. The advanced manufacturing production credit is also repealed for wind energy components several years earlier than for other eligible components.

Additionally, the legislation’s energy provisions do not seem to follow any principles of good tax policy. While the carbon oxide sequestration credit and the nuclear power production credit from the IRA are mostly retained in OBBBA, the clean hydrogen production credit will be eliminated after 2027. The clean fuel production credit is extended by two years, whereas the advanced manufacturing production credit for critical minerals is changed from permanent to temporary.

A perplexing modification in the OBBBA’s energy provisions is that it adds a new production credit for metallurgical coal, equal to 2.5 percent of production costs, under the advanced manufacturing production credit. Metallurgical coal is primarily used as a raw material for manufacturing steel, which is sold at a much higher price than thermal coal used for electricity generation. The United States is a major producer of metallurgical coal globally and most of the U.S. metallurgical coal products are for exports.

To price the externalities of greenhouse gas emissions and encourage transition to clean energy technologies, tax subsidies should ideally be as technology neutral as possible, meaning that they subsidize all clean energy technologies equally if they lead to the same amount of emissions reduction. Overall, there is significant room to improve the efficiency of OBBBA’s energy provisions as they arbitrarily pick winners and losers across different energy technologies.

Fiscal Sustainability

The IRA’s clean energy provisions were initially estimated to cost $400 billion from 2026–2035. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) later estimated that the cost of the provisions is more than double, at $870 billion.

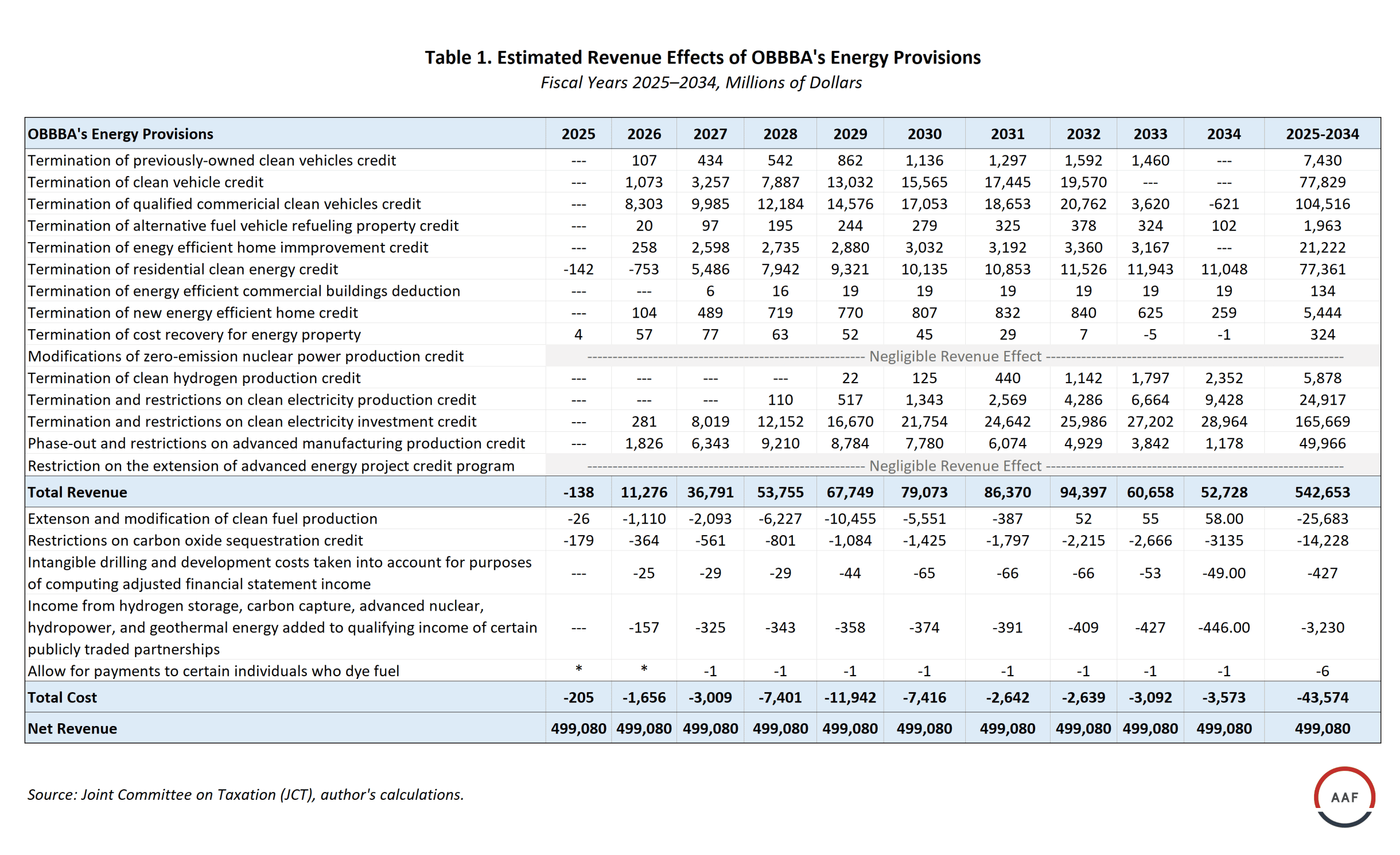

Table 1 shows JCT’s estimate of how much revenue the OBBBA’s energy provisions would raise. The termination and restriction of the energy provisions will raise about $543 billion from 2025–2034. The expansion of some of the energy provisions will cost about $44 billion over the same period. On net, all the OBBBA’s energy provisions will raise a total of $499 billion from 2025–2034.

AAF previously estimated that repealing all the energy provisions in the IRA would raise $852 billion from 2026–2035. The OBBBA’s energy provisions will raise approximately 60 percent of the total revenue if the legislation were to fully repeal all the energy provisions.

Note: * denotes an amount of less than $500,000.

Appendix: Repealing Energy Credits: IRA vs. OBBBA

Highlights of Expiration Dates, Exceptions, and Special Rules

| Energy Credits | IRA | OBBBA |

| Clean vehicle credit | Expired after December 31, 2032. | Eliminated after September 30, 2025. |

| Used clean vehicle credit | Expired after December 31, 2032. | Eliminated after September 30, 2025. |

| Commercial clean vehicle credit | Expired after December 31, 2032. | Eliminated after September 30, 2025. |

| Alternative fuel vehicle refueling property credit | Expired after December 31, 2032. | Eliminated for projects placed in service after June 30, 2026. |

| Energy efficient home improvement credit | Expired after December 31, 2032 | Eliminated for projects placed in service after December 31, 2025. |

| Residential clean energy credit | Expired after December 31, 2034. | Eliminated for projects placed in service after December 31, 2025.

|

| New energy efficient home credit | Expired after December 31, 2032. | Eliminated for qualified homes acquired after June 30, 2026. |

| Clean hydrogen production credit | Qualified facilities constructed before December 31, 2032 (credits available for the first 10 years of service.) |

Eliminated for projects beginning construction after December 31, 2027. |

| Clean electricity production credit | Will begin to phase out after the later of 2032, or when the United States meets the electricity sector’s emissions reduction goal. | For wind or solar, the credit is eliminated for facilities placed in service after December 31, 2027, except for such projects that begin construction before the date which is 12 months after the enactment of the law.

For all other qualified technologies, the full credit is available for facilities that begin construction by the end of 2033; the credit starts phasing out in 2034 at 75%, 50% in 2035, and is repealed in 2036.

FEOC restrictions.

Transferability is available, but no transfers to specified FEOC are allowed.

A new energy community bonus credit of 10% is available for advanced nuclear facilities based on employment.

Eliminates the credit for residential solar water heating and small wind property leased to a third party. |

| Clean electricity investment credit | Will begin to phase out after the later of 2032, or when the United States meets the electricity sector’s emissions reduction goal. | For wind or solar, the credit is eliminated for facilities placed in service after December 31, 2027, except for such projects that begin construction before the date which is 12 months after the enactment of the law.

For all other qualified technologies, the full credit is available for facilities that begin construction by the end of 2033; the credit starts phasing out in 2034 at 75%, 50% in 2035, and is repealed in 2036.

FEOC restrictions.

Adds a 10-year-recapture period for certain payments made to prohibited FEOC.

Transferability is available, but no transfers to specified FEOC are allowed.

Retains the domestic content bonus credit but makes it harder for taxpayers to be eligible by increasing the required domestic content percentages depending on the construction start date.

Eliminates the credit for residential solar water heating and small wind property leased to a third party.

Authorizes 30% credit for fuel cell property for projects that start construction after 2025. |

| Clean fuel production credit

|

Credit expired for fuels sold after December 31, 2027.

A credit is equal to the applicable amount (depending on the type of fuel) multiplied by an emissions factor. |

Expires for fuels sold after December 31, 2029.

Credit is not available unless the feedstock used to produce the qualified fuel comes from the United States, Mexico, or Canada.

Eliminates the enhanced credit rate for sustainable aviation fuel.

FEOC restrictions.

Transferability is available, but no transfers to specified FEOC are allowed.

Negative lifecycle emissions rates were eliminated except for animal-manure-based fuels. |

| Carbon oxide sequestration credit | Construction of the equipment must start by the end of 2032 (a 12-year credit is available after a facility is in service). |

No change to the expiration date in the IRA.

Increase the credit amount for utilization or use in oil and gas recovery to the same amount available for sequestration.

Transferability is available, but no transfers to specified FEOC are allowed.

FEOC restrictions. |

| Zero-emission nuclear power production credit | Expired after December 31, 2032. | No change to the expiration date in the IRA.

Transferability is available, but no transfers to specified foreign entities concerned are allowed.

FEOC restrictions |

| Advanced manufacturing production credit | The credit for critical minerals is permanent.

For other qualified components, the credit starts to phase out in 2030 with a reduction of 25% annually over four years. |

Adds an expiration date for the credit available for critical minerals.

Delays the phaseout schedule for all components (including critical minerals but not metallurgical coal) by one year: The credit starts to phase out in 2031 with a reduction of 25% annually over four years.

Wind energy components sold after December 31, 2027, are not qualified.

Adds a new production credit for metallurgical coal equal to 2.5% of production costs, which expires after 2029.

Transferability is available, but no transfers to specified FEOC entities concerned are allowed.

FEOC restrictions.

Adds strict restrictions to the credit available for qualified components integrated, incorporated, or assembled into another eligible component.

|

Source: Evaluating the IRA’s Clean Energy Tax Provisions, McGuireWoods, Holland & Knight, Pillsbury Winthrop Shaw Pittman, Frost Brown Todd, and author’s analysis.