Insight

July 21, 2021

Examining State Tech Policy Actions in 2021

Executive Summary

- State policymakers are seeking to address many of the same technology policy issues as federal policymakers, including content moderation, data privacy, and the digital divide.

- For many technology policy issues such as net neutrality, data privacy, and content moderation, state and local policy could create a disruptive patchwork that limits benefits to consumers and deters innovation.

- For other issues such as addressing the digital divide and regulating new technologies, states can serve as beneficial laboratories of democracy for different policy approaches and provide competing policy frameworks and incentives that encourage innovation.

Introduction

As efforts to regulate Big Tech have repeatedly stalled in Congress over the last several years, some states have passed or are considering their own legislation on technology policy issues including data privacy, content moderation, and antitrust. During the 2021 sessions, at least 38 state legislatures have introduced over 100 bills on such topics. But are state-level tech policy actions the right way to address tech policy concerns, or do they create barriers to future innovation that could be avoided by federal solutions?

For some tech policy issues, states can be useful laboratories of democracy by experimenting with different policy solutions, but for other issues, states risk creating a disruptive patchwork that deters innovation and limits what consumers can access. Because of the interstate nature of the internet and many other technologies, state laws regulating the internet can have a national impact. Those policy areas that remain within a state’s borders are ripe for state-level action. Without uniform regulation on many issues, however, tech companies may face a patchwork of regulation and have to repeatedly engage in costly compliance, with the ultimate result that consumers may be denied access to beneficial features available in other jurisdictions. This insight examines some of the most common state-level tech policy proposals that reflect broader national tech policy debates and identifies those policies that may disrupt both existing and emerging technologies, as well as those that support continued innovation.

Content Moderation Bills

Many on both the left and the right have questioned whether online platforms, particularly social media platforms, are properly engaged in content moderation. Some on the right allege that platforms are silencing conservative voices or caving to “cancel culture,” while others on the left argue platforms are not doing enough to stop the spread of hate speech and misinformation. Section 230, originally a part of the Communications Decency Act, is a law that provides liability protection for platforms carrying user-generated content and affirms their ability to engage in content moderation without such actions being subject to litigation. Many states have now considered their own legislation that could limit online voices and undermine a platform’s ability to engage content moderation decisions that serve their intended audiences.

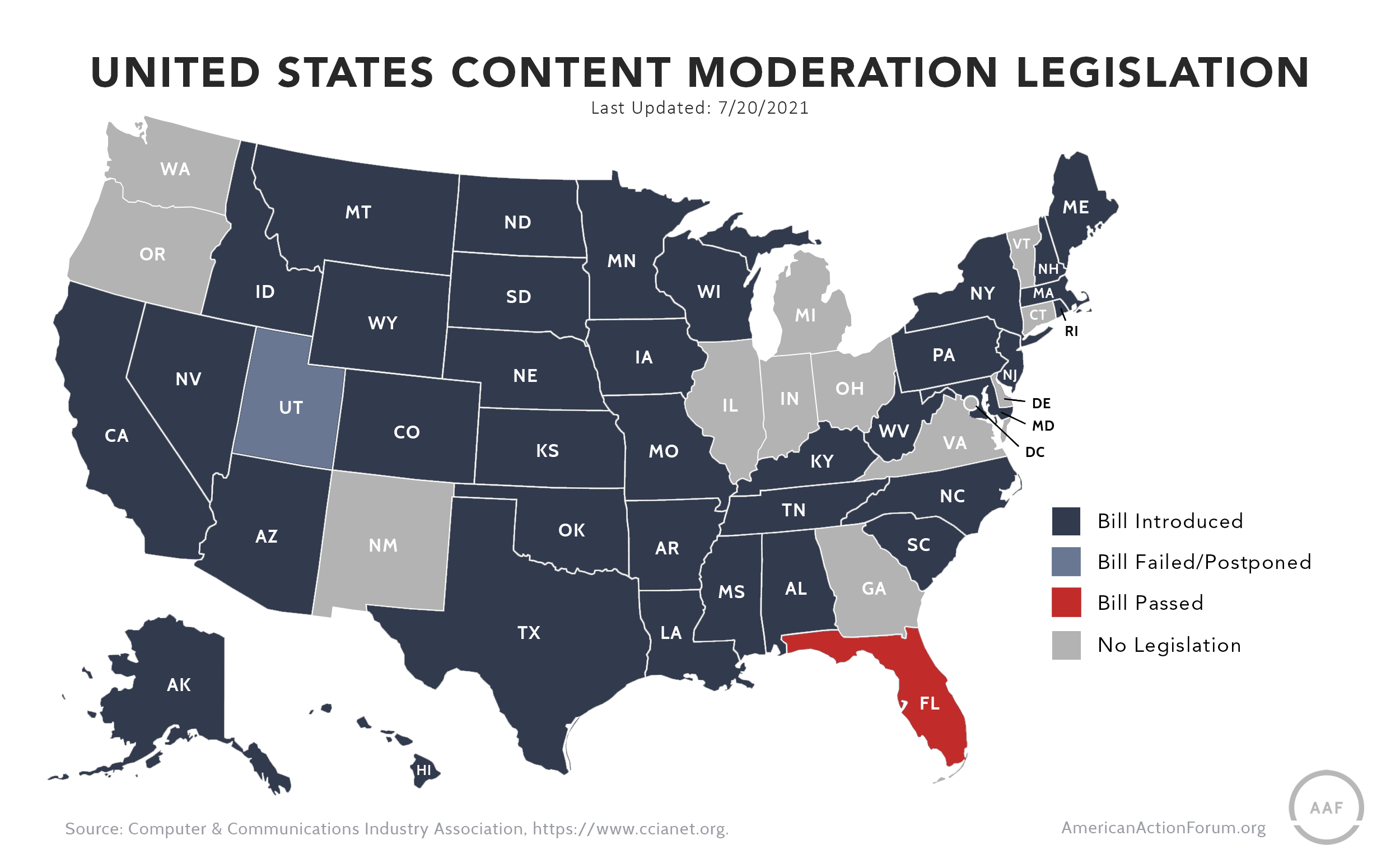

At least 30 state legislatures have introduced some form of a content-moderation bill in this legislative session. Many of these proposals are in conservative states and focus on perceived anti-conservative bias on social media platforms and the banning of former President Trump from Twitter and Facebook. Two notable examples of such proposals are in Florida and Utah. Florida passed a bill that will allow individuals to sue if they are censored without proper notice from Big Tech companies. This bill also prohibits social media sites from de-platforming political candidates during elections. The law is already subject to a preliminary injunction due to concern that it violates the First Amendment, and the legal challenges are ongoing.

State-level proposals to regulate content moderation are not limited to conservative states with Republican legislatures or governors. Democratic-led initiatives at the state level, much like Democratic-led initiatives in Congress, call for more content moderation from Big Tech and examination of responsibility for user content such as hate speech or misinformation. This includes recent statements from the Biden Administration regarding flagging problematic vaccine content and a surgeon general’s report condemning the role of social media platforms in spreading vaccine misinformation. State legislatures in California, Colorado, and New York, among others, have also considered proposals that would impact online speech and content moderation. The Colorado Senate introduced legislation to create a commission that would investigate claims regarding hate speech, conspiracy theories, and disinformation disseminated on social media platforms – and charge tech companies a fee for it. The bill was met with high scrutiny from First Amendment advocates and was amended in a way that turned the bill into a study. Ultimately, even that version failed in the House.

State-level content moderation bills raise similar issues as federal proposals when it comes to the First Amendment, but they also raise unique federalism concerns. Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act preempts most state-level actions that would undermine the uniform policy regarding liability for user-generated content. Even without such preemption, the interstate nature of most user interactions on platforms raises concerns about the extra-territorial implications of these policies. While policymakers may have compelling reasons to desire policy change, such issues are best addressed at a federal level instead.

One of the great benefits of the internet is the ability it provides people to connect with a range of users from around the world, but state laws could limit the ability of their citizens to connect with others. For example, the legal costs resulting from state laws that allow a private right of action against companies engaging in content moderation could be high enough to disincentivize smaller participants from entering a state’s market. As a result, a person’s state of residence alone could limit access to platforms, audiences, and discussions. Additionally, differing standards of objectionable content across state lines could bar members of certain communities from participating in important conversations. Explicit language, video, or graphics can be used to illustrate experiences and educate others, especially in marginalized communities and in instances of live breaking news; when one state moderates this type of content blindly, constructive voices are silenced, and content moderation has missed the mark.

Congress continues to debate whether antitrust reform is needed in the tech sector. In addition to antitrust litigation brought by state attorneys general against Amazon, Google, and Facebook, some states have considered bills that would either address specific concerns, such as restrictions on app store marketplaces, or more broadly reform the approach to antitrust at the state level.

The New York Senate recently passed the broadest state-led antitrust bill in the United States. Taking aim at Big Tech companies, the legislation would establish an “abuse of dominance” standard for companies with market shares as low as 30 percent. The standard is more closely related to European antitrust law than to the American approach focused on the consumer welfare standard. It would allow the attorney general and private parties to present evidence that a company has violated competition law not by harming consumers but by engaging in practices that may harm other policy goals or competitors, such as creating poor working conditions or engaging in behavior that leverages success in one market to enter another. It would also implement a pre-merger review requirement of acquisitions beginning at $9.2 million and harshen criminal penalties for tech companies. If successful, this bill would shift antitrust enforcement, at least in New York, away from the standard used generally by federal courts and could create confusion for businesses of all sizes.

Some states have also considered proposals that would address specific concerns related to competition in app-store markets. For example, Arizona and Rhode Island both considered bills that would regulate the ability of platforms such as Apple and Google to offer app stores, as some have claimed that the business practices associated with these offerings raise antitrust concerns. These proposals are often in response to claims that the business practices associated with these offerings raise antitrust concerns, but they take a limited view of the market involved. Additionally, similar to content moderation bills and data privacy bills, these proposals would make it difficult for platforms to offer the same app store or third-party marketplace in all states. While none of these proposals was ultimately signed into law, states considering such bills should consider not only the potential impact on large companies that such proposals might have, but also the impact on consumers and smaller businesses. The appropriate balance of federalism in antitrust is also receiving federal attention. Some policymakers have seen state attorneys general as part of a potential solution to concerns that there is a lack of antitrust enforcement. For example, recently Senators Amy Klobuchar (D-MN) and Mike Lee (R-UT), the chair and ranking member of the Senate Judiciary Committee’s antitrust subcommittee, introduced legislation they say would “empower state antitrust enforcers.” This proposal was included with the broader package of antitrust reforms that recently passed the House Judiciary Committee. As in many areas of law, there are splits between federal and state authority over antitrust enforcement. In addition to making federal claims against companies, state enforcers may also be arguing state-specific consumer protection claims in state courts.

In a way similar to other issues, a variety of more aggressive antitrust regulations could create a patchwork across the country that undermines the ability of firms to access consumers and the ability of consumers to access beneficial products.

Data Privacy

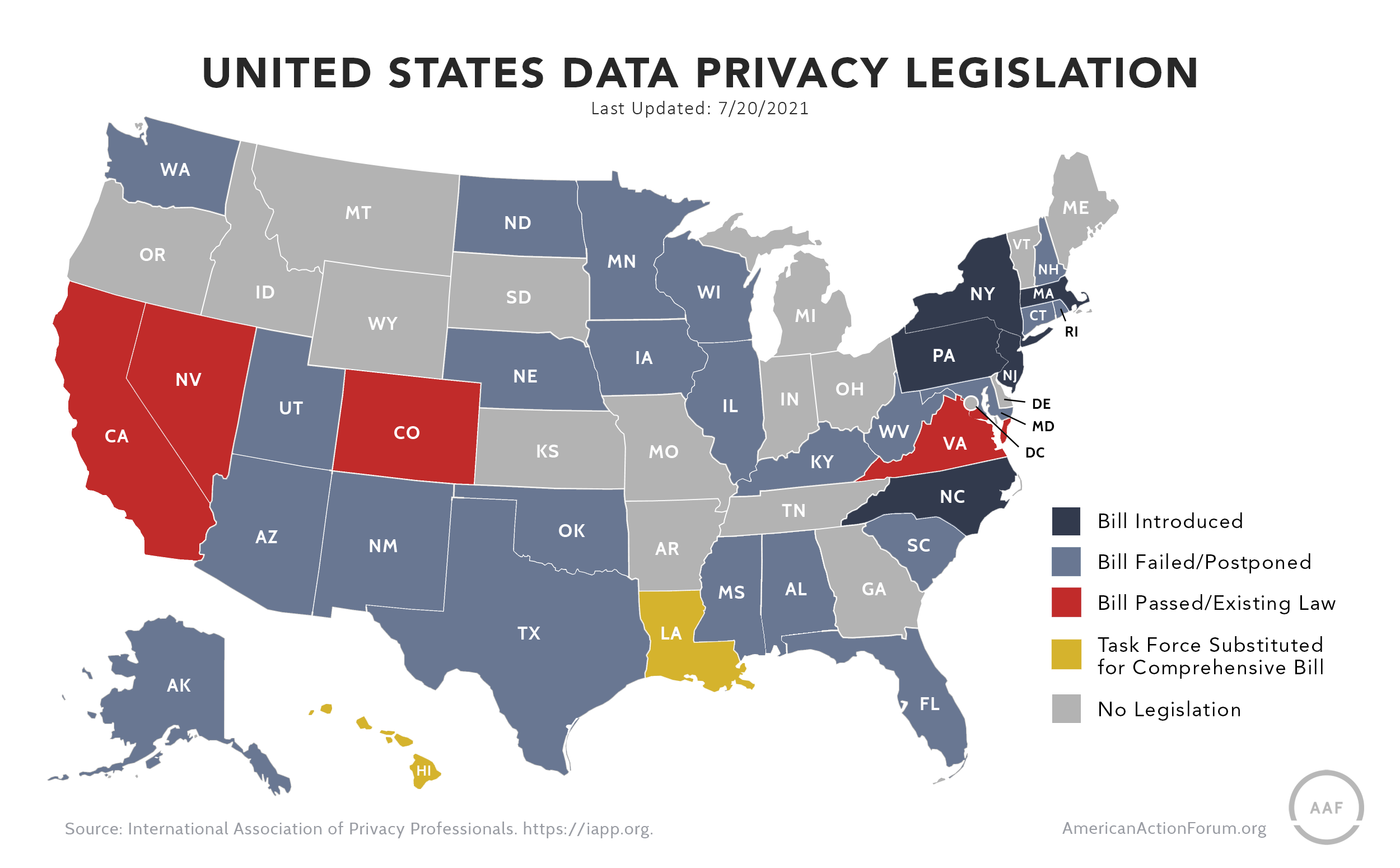

Many states are considering data-privacy laws, which raises similar concerns about an emerging patchwork of regulations across the country.

Following the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), which was passed in 2018 and implemented in 2020, many other states have drafted bills to protect data privacy. This past legislative session, Virginia became the second state to pass such a bill, though it is far less restrictive than California’s. . Like the CCPA, the Virginia Consumer Data Protection Act (VCDPA) allows consumers to retain and delete their data as well as opt out of data collection by tech companies. The bill, however, is tailored more narrowly in terms of which companies will be subject to its requirements and what personal data is considered sensitive and thus protected. The Virginia bill garnered support from many companies such as Microsoft and Amazon and may serve as the federal framework for industry lobbyists.

In addition to these laws, in four states there are currently six data privacy bills under consideration that resemble the CCPA. There have been other efforts, however: Thus far in 2021, 19 bills in 16 other states were either killed in committee or postponed to a later date, according to the International Association of Privacy Professionals.

Following the 2017 repeal of the federal government classifying internet service providers under Title II, several states have attempted to pass their own net neutrality requirements either generally or when engaged in specific types of service provision such as government contracts.

Seven states have already adopted their own net neutrality laws: California, Colorado, Maine, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington. Additionally, Connecticut, Kentucky, Missouri, New York, Oregon, South Carolina, and Texas have had net neutrality bills introduced in the 2021 legislative session.

As with data privacy, there are concerns about the disruption such bills could create both for local users and for the deployment of broadband services. For example, a telehealth app designed for veterans was uncertain if it could offer its product in California due to the state’s net neutrality law.

The federal position regarding state net neutrality laws has shifted with the change in administration. The Trump Administration had previously joined a legal challenge to the California net neutrality proposal; the Biden Administration is no longer continuing this challenge. This shift does not change the potential negative effects of these laws, as they could have a patchwork effect on internet service providers or hurt the ability of companies to provide certain products in these states. While many debate the appropriate regulatory framework at a federal level for internet service providers, state-level net neutrality proposals could create additional challenges both in those states and beyond.

Digital Services Tax

During this last legislative session, Maryland became the first U.S. state to pass a digital services tax. Nine states in total are considering some measure related to digital advertising.

Such taxes have been previously passed in European countries seeking additional tax revenues from U.S. companies with a large digital footprint abroad. These taxes are novel and atypical, which has discouraged the United States from awarding foreign tax credits to firms facing digital services taxes abroad. The increased costs of these taxes are likely passed on to consumers, as third-party sellers and advertisers will face higher costs to be hosted on a platform and buyers assume those costs on the backend.

The decision of a state to engage in a similar taxation policy raises not only similar economic concerns as those posed by the use of these taxes internationally, but also additional legal challenges due to the state-federal relationship. An analysis by the Tax Foundation argues these proposals likely violate the federal Permanent Internet Tax Freedom Act and are burdensome, difficult to administer, and generally an economically inefficient way to achieve policy goals related to changing industry behavior.

Sandboxing and Innovation-Friendly Regulatory Reform

While the issues discussed thus far tend to not benefit from state-level action, there are some areas where state-level efforts are beneficial. Regulatory reform is one such area. Many states continue to explore flexible regulatory options to promote innovation in a range of heavily regulated industries such as transportation and financial services. While many states have tried various innovation-supporting “sandboxes” in specific industries, this year Utah passed a first of its kind universal sandbox that will allow innovators in any industry to apply.

Sandboxes are a policy tool that allows those who wish to provide a product or service that would currently be disallowed under current regulations but which they believe will benefit consumers to apply to regulators for an exemption from that regulation. These exemptions are typically temporary and accompanied by other regulatory requirements such as reporting. Sandboxes have been successfully implemented in highly regulated industries such as finance to allow innovative technologies to engage in small scale testing. Other similar examples include pilot programs for new transportation technologies such as those used by many cities regarding scooters.

As the American Action Forum’s Dan Bosch and Thomas O’Rourke wrote earlier this year, in addition to the potential use of sandboxes in reexamining existing regulations, “Utah hopes to drive innovation by reducing regulatory barriers for companies with high growth potential. In turn, improving the environment for innovation will result in more widespread economic benefits, such as job growth and increased tax revenue.” Sandboxes are one example of how states can test regulatory policies and keep pace with innovation in various industries, while still considering a balanced approach to regulatory actions and ensuring consumers are protected.

Expanding Broadband Access and Closing the Digital Divide

2020 and 2021 have highlighted concerns about those households or individuals who are un- or under-connected to high-speed internet. States and local governments are often better positioned than the federal government to identify the specific needs and reasons why those in their communities lack sufficient internet services. The result of this local knowledge can be creative solutions and public-private partnerships that work to fill specific needs.

Several states have taken action to try to solve this problem not only during the pandemic, but to ensure policy supports continued deployment and improvement around internet connectivity. For example, Louisiana passed “dig once” legislation that allows fiber for high-speed internet to be laid at the same time as road construction. Other states sought to fulfill more immediate needs through issuing vouchers, WiFi hotspots, or devices to eligible households.

The digital divide remains a complicated and multi-faceted issue that will need a diverse range of solutions. State policymakers will need to continue to respond to immediate needs while also considering the impact various policies can have on innovation and deployment. Such policies may include not only assisting in improved mapping and examining existing regulatory barriers and fees associated with deployment, but also ensuring policies are appropriately addressing the reasons some have not adopted high-speed internet access.

Conclusion

As these most recent state legislative sessions reveal, many states are engaged in the same tech policy debates that are occurring at a federal level. For matters that remain within a state’s borders, such as improving its connectivity levels or the appropriate levels of regulation, states can move more swiftly than the federal government and establish creative policy solutions that could serve as models for tech policy in other states or at a federal level. Because many tech policy debates are naturally interstate in their nature, however, state actions on issues such as data privacy, net neutrality, and content moderation risk creating a disruptive patchwork that could deter innovation and diminish the benefits of existing technologies for its own citizens.