Insight

September 1, 2022

FTC Needs to Run Those Numbers Again

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) recently published a proposed rule seeking to establish more rigorous regulatory standards for automobile dealerships that – especially for an agency known for its enforcement actions – stands as its most significant rulemaking action in recent memory.

- The FTC expects the proposal to yield tens of billions of dollars in benefits due primarily to time savings for consumers, but a closer look at the agency’s underlying assumptions and emerging market trends suggests that such estimates are dramatically overstated.

- The proposal’s cost calculations take an overly conservative estimate that, when adjusted to account for more realistic circumstances, make the benefits-to-costs ratio appear at best to be roughly even, in contrast to the 30-to-1 benefits-to-costs ratio put forth in the rulemaking’s current analysis.

INTRODUCTION

For many people, the process of buying a car can be a challenging, albeit important one. The amount of effort and time involved in acquiring what is likely one of a person’s most valuable material assets (outside of perhaps their home) can be extensive. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – armed with regulatory authority granted to it by the Dodd-Frank Act of 2010 – has recently decided to step into the fray here with a proposed rule that would require more rigorous cost disclosure requirements for automotive dealers.

Beyond simply the subject at hand, this proposal is notable because it represents the first time in at least recent history that FTC has promulgated a rulemaking of this magnitude with a cost-benefit analysis. Considering how relatively novel this may be for an agency that is traditionally more focused on enforcement instead of rulemaking, it is perhaps unsurprising to find that, upon greater scrutiny of some key assumptions, the monetized cost-benefit balance is potentially closer to even, if not on the net-cost side, than the roughly 30-to-1 benefits-to-costs ratio the agency’s current calculations suggest. Having billions of dollars of potential impact hinge on a few flawed assumptions should give FTC pause and perhaps spur a re-evaluation of this rulemaking’s overall direction.

A NOVEL RULEMAKING FOR FTC

According to FTC, “many of the problems observed in the motor vehicle marketplace persist in the face of repeated federal and state enforcement actions, suggesting the need for additional measures to deter deceptive and unfair practices.” As such, the agency is invoking its authority under Section 1029 of the Dodd-Frank Act to “to prescribe rules with respect to unfair or deceptive acts or practices by motor vehicle dealers.”

In particular, the key parts of the proposed rule’s potential new regulatory standards include: “Requiring dealers, whether acting directly or indirectly, to refrain from misrepresentations, provide for material disclosures at key points in the transaction, refrain from the sale of deceptive or unfair add-on products, and require retention of dealers’ advertisements and consumer transaction documents.” Enshrining these provisions into relevant regulatory code would allow FTC to utilize its authority under Section 19 of the FTC Act to bring legal action against “any person, partnership, or corporation,” in the automobile dealer industry, that “violates any rule under [the FTC Act] respecting unfair or deceptive acts or practices.”

Per FTC’s economic analysis, this proposal would impose nearly $1.4 billion in total costs on automobile dealers to provide roughly $31 billion in benefits to consumers, primarily through expected time savings in the car-buying process. Given the magnitude of these figures, it is one of the more consequential rulemakings of the year thus far. Moreover, it represents (by a wide margin) the most economically significant FTC rulemaking currently on record.

The American Action Forum’s (AAF) RegRodeo contains 28 rules from FTC since 2005 that had some quantified cost or paperwork estimate. The most significant rule recorded in RegRodeo beyond this current proposal is a 2010 rule (jointly produced with the Federal Reserve) regarding credit reporting practices that brought an estimated $252 million in total costs. No other proposed or final rule from FTC has costs that exceed the $100 million threshold (since 2005, at least).

Of note, while virtually all of the FTC rulemakings included in RegRodeo draw their estimated economic impact from their discussions of paperwork burdens, this FTC proposal includes a full-blown “Preliminary Regulatory Analysis” that mirrors much of the same structure as other agencies’ cost-benefit analyses. This is because a statutory requirement (Section 22 of the FTC Act, 15 U.S.C. 57b-3,) compels FTC to produce such an analysis. Despite being statutorily required, however, a search of FTC final rules that address this provision at all currently yields five entries (essentially 1.2 percent of the more than 400 final rules from FTC currently posted on federalregister.gov).

Yet all five of these entries only mention this cost-benefit analysis section by way of establishing that they do not meet the economic impact threshold that would require a full analysis. As such, if this current automotive dealer proposal were to become finalized it would represent the only FTC rule (currently available online, at least) to ever trigger this provision. Given its singular nature, it is more understandable that – as discussed in the following sections – perhaps an agency historically more focused on handing out enforcement decisions on antitrust proceedings could use more refinement in its cost-benefit calculations.

EXAMINING THE BENEFITS

Core Time Savings Estimate

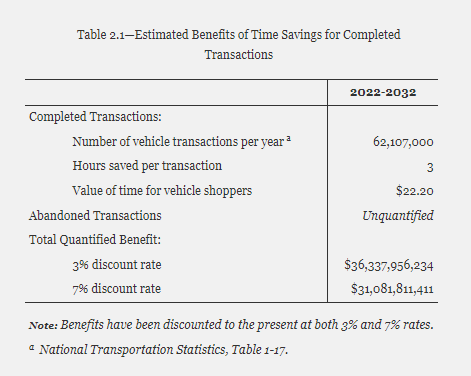

FTC discusses a number of qualitative benefits this proposed rule could produce, but in terms of quantified benefits its core contention boils down to the following table:

Essentially, FTC expects that the clarity afforded to the average consumer by these newly required disclosure materials would save this typical consumer three hours in their car-buying experience.[1] The agency then applies the monetary value of this avoided opportunity cost and extrapolates it out to the overall total number of transactions in a year. This “three hours saved” figure is the most questionable component of these calculations.

In footnote 180, FTC explains its assumption thusly:

According to the 2020 COX Car Buyer Journey study, consumers spent roughly 15 hours researching, shopping, and visiting dealerships for each motor vehicle transaction. 3 hours corresponds to 20% of an average consumer’s time spent on such activities. Cox Automotive, 2020 Cox Automotive Car Buyer Journey 5-6 (2020), available at https://b2b.autotrader.com/app/uploads/2020-Car-Buyer-Journey-Study.pdf.

First, it should be noted that the FTC doesn’t cite the Cox study to support its assertion that the proposed rule will save consumers three hours per transaction. Indeed, the FTC cites the Cox study only to support the claim that consumers spend a total of 15 hours purchasing a car. The FTC then simply calculates 20 percent of 15 hours, and thus arrives at its conclusion that three hours will be saved per transaction.

But even if this 20 percent reduction in transaction time seems plausible and reasonable on its face, a closer look at the very report the FTC cites calls that into question. Take page 36 of said report:

In this breakdown of the time spent at a dealer, the only item that this rulemaking would materially affect would be the 32 minutes spent “Negotiating a Price and Trade-In Offer;” all other aspects of this estimated “visit” are rote aspects of the process that largely fall outside the scope of the new requirements. While these increased disclosures may have some ancillary savings to the pre-visit time or time spent at another dealership, it is difficult to see how one can expect 3 hours of savings when the primary aspect of the car-buying process that the proposal seeks to address is roughly half an hour. If one applies 30 minutes saved (instead of the original 3 hours) to FTC’s benefits formulation, it yields only $689 million in annual benefits, or $5.2 billion in present value under a 7 percent discount rate.

Broader Market Trends

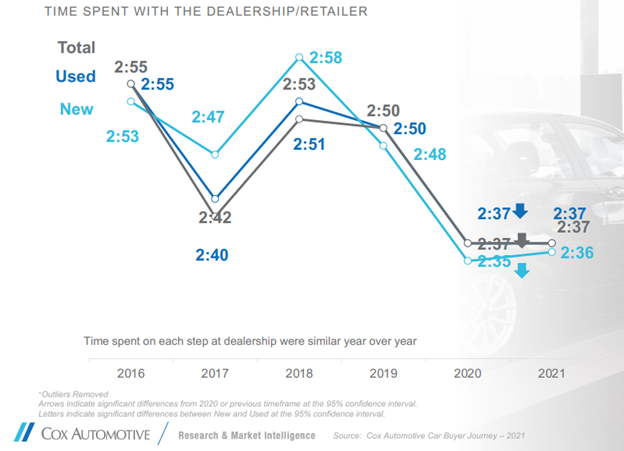

Beyond the exact components of FTC’s current calculations, there is also the issue of how changing market conditions may provide diminishing returns in terms of the amount of time savings benefits a regulation like this can really draw from the car-buying process going forward. For instance, take this chart from the 2021 Cox report:

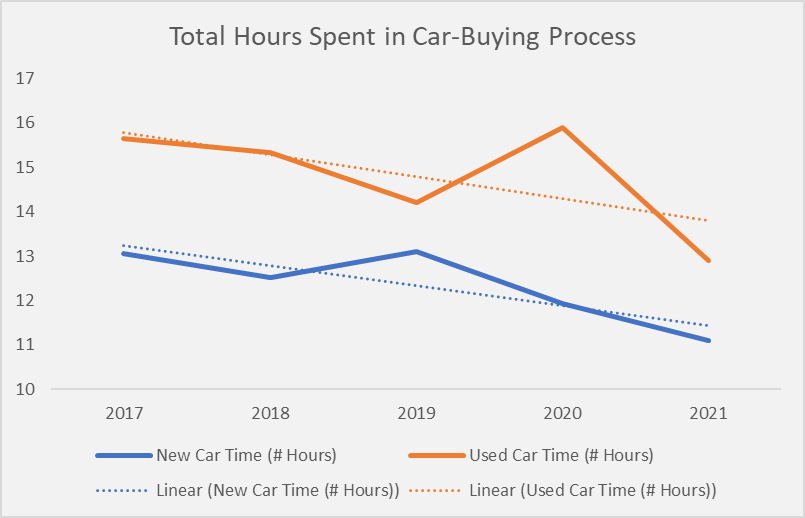

These data suggest that, in recent years, the time spent interacting with a dealer has generally declined. Examining further data across the past few years of reports suggests that this trend also applies to the overall buying process (from research to purchase):

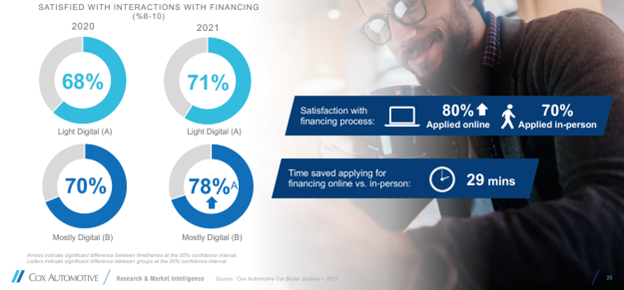

These trends make some sense intuitively as consumers have moved toward online sources for either: A) background research on features and pricing to leverage during in-person negotiations, or B) online dealer portals that market themselves as low- or no-hassle operations. Another portion of the 2021 Cox report demonstrates one aspect of this phenomenon:

As consumers continue to gain relative advantages in terms of time savings and increased satisfaction due to these already-occurring market trends, it raises the question of how many more benefits a rulemaking like this could squeeze out of the process – and thus, calls into question the rationale for such a dramatic rule.

EXAMINING THE COSTS

The costs portion of FTC’s economic analysis also suffers from some questionable assumptions that, if adjusted, could potentially shift the calculations involved in such a way that their magnitude becomes comparable to the agency’s potential benefits, further eroding the rationale for the rulemaking. The most substantial portion of FTC’s cost estimates comes in its calculation of the cost to dealers in disclosing accurate pricing information regarding potential “add-ons”:

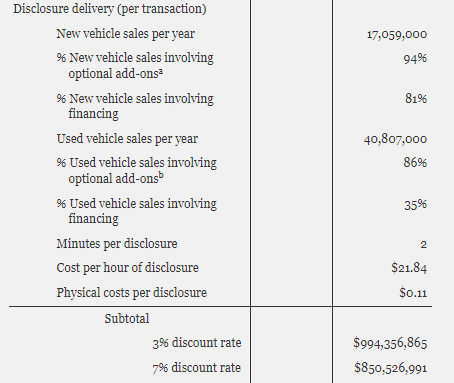

The calculation here is that each disclosure costs the dealer two minutes in labor costs and 11 cents in materials that is then extrapolated as: “One disclosure is required for all new and used vehicle sales, an additional disclosure is required for transactions with optional add-ons (94% new and 86% used), and a third disclosure would be required for financed transactions with optional add-ons (76% new and 30% used).” This requirement accounts for a majority of the proposal’s overall cost estimate.

The issue with this calculation, however, is that FTC only applies it once for each transaction. See footnote 187:

One consequence of this provision is that consumers, with the benefit of clear disclosure of the various prices, will renegotiate some aspect of the sale in order to obtain a more favorable deal. Any such renegotiation would require the completion of another disclosure prior to consummating the transaction, which is assumed away here. [emphasis added]

FTC acknowledges that having this additional information will spur more negotiation, which will in turn require additional disclosures and the commensurate costs from such. Nevertheless, its current topline cost estimate is largely based on the (unlikely) assumption that there will only be one disclosure per transaction.

Perhaps this assumption stems from the lack of data available on the question of “how many specific negotiation points would require this disclosure?” Turning back to the 2020 Cox report (the 2021 version did not contain these data), however, one can find at least a potential baseline to this question. Take, for instance, this section:

According to this, each eventual transaction involves the buyer visiting at least two dealerships. One can reasonably assume that there would thus be at least one “disclosure point” at each dealership. Doubling up this disclosure cost section would yield total costs of $1.7 billion. If one merely assumes that there are, say, three “disclosure points” at each of these two dealership visits to yield a six-fold increase in add-on disclosure costs, that would bring total costs of $5.1 billion. If one simply adds on the roughly $510 million for all other cost subsections as they currently stand per FTC’s estimation, then the proposal’s total costs would exceed its benefits under the half-hour savings scenario discussed earlier.

CONCLUSION

It is often easy to see why the car-buying experience is a vexing one for many consumers. Between the high economic stakes, potential information asymmetry, and incentives for dealers to “upsell,” purchasing a car can be a challenging process. Yet with greater amounts of information available online for consumers and an increasing prevalence of dealers that make of point of taking the “haggle” out of the process, it is difficult to assert that consumers are suffering from a clear market failure in the automotive sales industry that requires dramatic FTC intervention. In fact, the proposed rule contains minimal quantitative assessments that federal agencies typically rely on to justify the need and cost of such comprehensive rulemakings. Even if one grants FTC’s overall rationale, one hopes that the agency would be thorough and deliberative in drafting its most significant rulemaking in modern times. Yet the potential flaws in the FTC’s calculations reveal a lack of analytical rigor – perhaps driven by a relative lack of familiarity with considering cost-benefit balances – that raises significant questions about the underlying merits of this rulemaking.

[1] Although it should be noted, there is a possibility that the proposed rule could actually increase the length of the average motor vehicle transaction. The rule would require several additional disclosures, including a number that must be signed by the customer and countersigned by the dealer. This additional material could confuse consumers and drive additional questions and increased transaction times.