Insight

March 27, 2025

FTC Set to Examine Occupational Licensing

Executive Summary

- On February 26, 2025, Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chairman Andrew Ferguson issued a directive forming a joint labor task force consisting of the directors of the Bureaus of Competition, Consumer Protection, and Economics, and the Office of Policy Planning.

- Chairman Ferguson directed the task force, among its other policy pursuits, to investigate harms to workers from occupational licensing, specifically in cases where “employers or professional associations advance or promote needless occupational licensing restrictions that can serve as an unwarranted barrier to entry and reduce labor mobility.”

- The FTC should advocate for state-based reforms to occupational licensing regimes and study how professional associations heighten barriers to entry through increased occupational licensing requirements.

Introduction

On February 26, 2025, Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chairman Andrew Ferguson issued a directive forming a joint labor task force consisting of the directors of the Bureaus of Competition, Consumer Protection, and Economics, and the Office of Policy Planning.

The directive instructed the task force to investigate “deceptive, unfair, and anticompetitive labor practices.” Among the priorities outlined for investigation by Chairman Ferguson were harmful occupational licensing requirements, specifically in cases where “employers or professional associations advance or promote needless occupational licensing restrictions that can serve as an unwarranted barrier to entry and reduce labor mobility.”

Occupational licensing, typically governed at the state level, requires workers to obtain government permission to legally perform certain job functions. In the 1950s, one-in-20 workers required a license to perform their job. That share swelled to one-in-five in 2024. While he decades-long shift in labor market composition from goods-producing to service-providing industries in part expanded the breadth of occupations subject to licensing, the bulk of the increase stemmed from an expansion in the number of professions requiring a license.

Occupational licenses act as market gatekeepers to professional access and mobility with scant evidence of increased quality or safety. The FTC should advocate for state-based licensing reforms and study how professional associations heighten barriers to entry through increased occupational licensing requirements.

The Rise of Licensing

Occupational licensing, or licensure, is a form of government regulation that requires individuals to obtain a license to practice a particular profession for compensation, with the often-stated goal of protecting public health and safety.

Occupational licenses, consequently, erect barriers to worker entry, often requiring a mix of minimum education and training, exams, and fees. Some licensing regimes require workers to meet specific character requirements or have a clean criminal record, while others necessitate continuing education or professional development to maintain the license. Occupational licenses also limit a worker’s mobility as they are typically governed at the state level: A license issued in one state is not always recognized in another.

Initially applied to medical and legal professionals as a means of establishing legitimacy in these critical fields, occupational licensing in the United States emerged around 1870. Yet occupational licensing requirements have increased over the past 70 years, aiming to protect consumers from unsafe or low-quality services. In the 1950s, just one-in-20 workers was subject to licensure; that figure was over one-in-five in 2024. Recent research found that 46 occupations, ranging from esthetics and barbery to those in technical and skilled trades, have obligatory licenses across all 50 states and the District of Columbia.

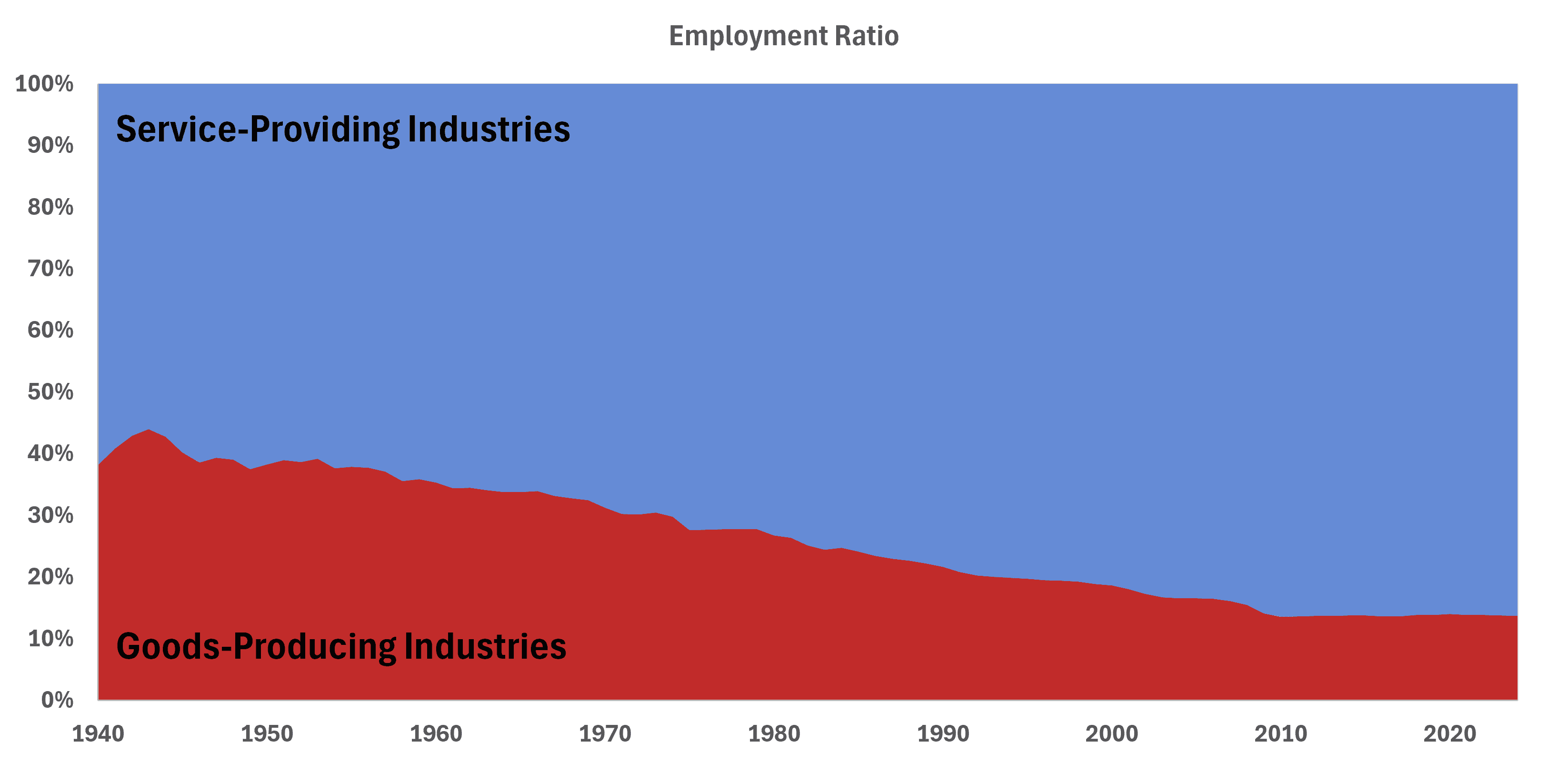

Service-providing professions are more likely to be subject to occupational licensing requirements than are goods-producing careers. This, in part, explains why the share of workers subject to occupational licensing requirements has ballooned. In 1940, 38 percent of employment was in the goods-producing sector. In 2024, goods-producing employment accounted for just 14 percent of all employment while service-providing jobs made up 86 percent (Figure1).

Figure 1

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

Yet structural changes to employment accounted for just a fraction of the increase in the burgeoning number of occupational licenses. Research from the Department of the Treasury found that two-thirds of the increase stemmed from an expansion in the number of professions requiring a license. In other words, occupational licenses have grown far beyond their traditional scope.

The Dirty Details of Licensing

The Bureau of Labor Statistics provides a summary of the licensing status of the employed by occupation in 2024. Unsurprisingly, 62.2 percent of those employed in the legal occupations have a license while 71.3 percent of health care practitioners and technical occupations also operate with a license. Meanwhile, 7.7 percent of production occupations – workers who operate machines and other equipment to assemble goods or distribute energy – have a license.

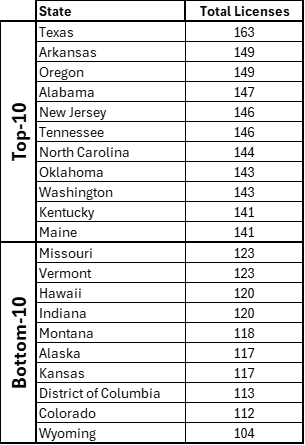

The 2024 State Occupational Licensing Index from the Archbridge Institute details occupational licensing requirements by state and occupation. Figure 2 displays the 10 states with the greatest and fewest number of occupations subject to licenses.

Figure 2

*Created using data from The Archbridge Institute’s State Occupational Licensing Index 2024 Master Data

Among the most controversial aspects of occupational licensing is the seemingly arbitrary nature of the requirements. The difference among the states in fees and educational requirements varies dramatically for the same occupational license.

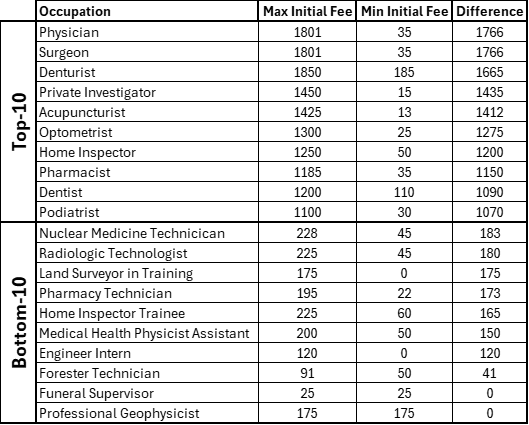

The Knee Regulatory Research Center at West Virginia University compiled data on the state-specific requirements for each occupational license, including the initial fee and the hours of hands-on experience required. Figure 3 shows the maximum and minimum fee for several occupational licenses and is organized by the difference in these fees. The 10 occupations with the greatest difference and the 10 with the smallest difference are included in the table.

Figure 3

*Created using data from the Knee Regulatory Research Center at West Virginia University

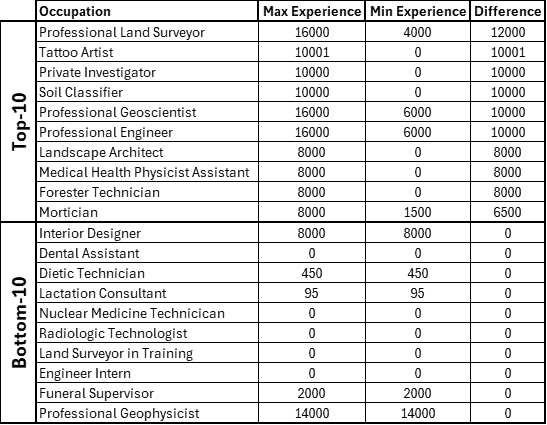

Similarly, Figure 4 shows the maximum and minimum hours of experienced, also organized by the difference.

Figure 4

*Created using data from the Knee Regulatory Research Center at West Virginia University

As shown in Figure 3, a physician is required to pay an initial fee of $1,801 to receive an occupational license in California, but only $35 in Pennsylvania. To be a professional land surveyor in Washington requires 16,000 hours of experience compared to 4,000 hours in states including Vermont, Wisconsin, and Maryland, among others.

These disparities call the methodology of the state licensing boards into question: Are they designed to protect consumers and ensure quality, or are they unnecessary barriers to entry designed to protect incumbents?

In testimony before the House Judiciary Committee, Subcommittee on Regulatory Reform, Commercial and Antitrust Law, then acting FTC Chairwoman Maureen Ohlhausen offered some insights into the risk of occupational licensing boards staffed by incumbent practitioners. Ohlhausen testified that “occupational regulation can be especially problematic when regulatory authority is delegated to a board controlled by active market participants – members who work in, and may derive much or all of their income from, the very occupation they regulate.” She added that “when financially-interested members control or dominate a board, there is a risk that the board’s decisions will serve the private economic interests of its members, not the policies of the state or well-being of its citizens.”

Economic Effects and State Reforms

Occupational licensing necessarily restricts the supply and mobility of labor. Barriers to entry – including education requirements, exams, and fees – reduce the supply of labor while state-specific licensing requirements limit labor’s mobility.

In the same testimony, Ohlhausen stated that the reduction in the supply of labor can lead to higher prices, reduced convenience or quality, and other labor market distortions. She claimed that licensing “is estimated to result in 10-15% higher wages for licensed workers relative to unlicensed workers, after adjusting for differences in education, training and experience” and leads to “higher prices for consumers.” Ohlhausen cited a 2011 study that estimated “license-related restrictions have resulted in as many as 2.85 million fewer jobs nationwide, with an annual cost to consumers of up to $203 billion.”

As the economic literature continues to measure the negative impact on labor supply and mobility and the increased costs on consumers, a recent flurry of state occupational licensing reforms has taken place in recent years.

As of 2024, 26 states have adopted some form of universal licensing recognition, and others are actively reviewing burdensome licensing laws. States have also considered alternatives to occupational licensing including voluntary certification, registration and mandatory bonding, state certification, and inspections. Service providers can take voluntary actions such as obtaining accreditation to serve as a testament to their quality of service. Government interventions such as inspection can also be taken as a more tailored option to protect consumers. Registration and bonding, a type of financial guarantee that a contractor purchases from a surety company, can also be an alternative to operating legally in a profession while allowing consumers to file a claim or complaint against the contractor’s bond or insurance. Another option would be to establish a commission consisting of government officials, industry experts, policy analysts, consumer advocates, and legal experts to review licensing laws to identify less restrictive consumer protections, assess necessity, and reduce excessive requirements.

Furthermore, in the age of social media, reviews regarding service and service quality are far more detailed and valuable than a provider’s license status, as industries prioritize hiring those with good rapport. A multi-state analysis comparing consumer ratings on Yelp found that in seven of nine comparisons, stricter licensing requirements did not correlate with higher service quality, affirming the idea that consumer feedback can be an equally strong, if not stronger, measure of service standards.

The Path for the FTC

State Advocacy

The FTC’s advocacy arm has routinely commented on specific state legislation governing occupational licenses and published studies quantifying the effects of overly restrictive licensing rules. These tools should continue to be part of the FTC’s arsenal as it advocates for the removal of overly burdensome labor restrictions.

An FTC study published in 2018, for example, discussed how occupational licensing “inherently restricts entry into a profession and limits the number of workers” and explained how this reduced supply “can restrain competition, potentially resulting in higher prices, reduced quality, and less convenience for consumers.”

Professional Associations

Chairman Ferguson’s labor force directive identified professional associations that “promote needless occupational licensing restrictions that can serve as an unwarranted barrier to entry and reduce labor mobility” as a potential target for enforcement.

Professional associations do not impose occupational licenses, but that is not to say they have no influence over the requirements. Indeed, research found that an occupation is about 15 percentage points more likely to be regulated in states with a professional association. The research also discovered “no evidence that the probability of regulation was increasing prior to the formation of professional associations, supporting a causal interpretation” of the estimates. Another study concluded that professional associations “often lobby legislatures to license specific occupations…and work with licensing boards to adopt model rules or best practices that these national associations promulgate.”

While the directive did not name specific professional associations, recent research provides an example of what sort of activity could warrant scrutiny. A recent report from the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) – the governing body that establishes requirements for entry into the Certified Public Accountant (CPA) profession, administers the entrance exam, and is made up of incumbent practitioners – found a 33-percent decline in first-time candidates taking the national CPA exam from 2016 to 2021. A 2024 study from the University of Chicago found that the prime contributor to the shortage in CPAs is the 150-hour rule. In 1988, the AICPA membership voted to increase the educational requirement for entry into the profession from four years (120) hours at an accredited university or college to five years (150 hours), with the stated goal of improving the ability of accountants to function in a complex, modern economy. States adopted the AICPA requirement between 1983 and 2015.

The study also cited other recent research published in the Journal of Accounting Research that concluded the 150-hour rule “reduced the number of first-time candidates for the CPA exam by 15%, had no discernible effect on their written communication skills, and had no discernible effect on the retention of CPAs in public accounting.” In other words, new CPAs were no more productive than before the rule change despite the 25-percent increase in education costs. Consequently, the study concluded that “CPA firms were unable to offer [new recruits] sufficient additional compensation to cover the cost of an extra year of tuition and foregone earnings.” The rule, crafted by incumbent practitioners, created an artificial shortage in the supply of CPAs by erecting a barrier to entry into the profession.

Recently, Utah passed legislation eliminating the 150- and 120-credit hour requirements for CPA licensure in state statute. Virginia and Ohio also cut the 150-hour rule.

While it is unclear whether the FTC is interested in this specific case, it is likely that the agency will investigate whether increased barriers to entry are designed to improve the quality of the labor force or to protect incumbents from an increased supply of labor.

Potential Roadblocks to Enforcement: State Action Doctrine

State governments regulate occupational licenses and the boards that develop and administer the requirements. State action – a legal doctrine – typically shields state regulatory regimes, including occupational licensing boards, from federal antitrust scrutiny.

To qualify for federal antitrust immunity, the occupational licensing board must satisfy two requirements: 1) It must take actions that are pursuant to clearly articulated state policy and 2) are actively supervised by the state.

Yet states routinely require licensing boards to include active market participants. Indeed, research examining all 1,790 occupational licensing boards found that 1,515 are required by state statute to be “comprised of a majority of currently licensed professionals, active in the very profession the board regulates.”

This conflict of interest was the subject of the Supreme Court’s decision in North Carolina Board of Dental Examiners v. FTC, in which the Court held that “‘a state board on which a controlling number of decisionmakers are active market participant in the occupation the board regulates’ must be actively supervised by the state or else face antitrust lawsuits brought by private parties and government enforcers.” The aforementioned study found that that “few states even arguably supervise their boards,” opening the possibility of federal antitrust enforcement.

Moreover, it is also likely that many of these active market participants are members of a state or national professional association, which could create an even greater incentive to erect barriers to entry to protect existing practitioners at the expense of workers and consumers.

Other Past Precedents

As the FTC contemplates potential enforcement actions, Ohlhausen described another instance in which an occupational licensing board was not protected by state action.

In 2003, the FTC sued the South Carolina Board of Dentistry alleging it had “illegally restricted the ability of dental hygienists to provide basic preventive dental services in schools.” In this case, the state legislature eliminated the “statutory requirement that a dentist examine each child before the hygienist could perform basic preventive care in schools,” but the board “re-imposed the dentist examination requirement as an “emergency regulation.” The FTC alleged that the board’s actions “unreasonably restrained competition in the provision of preventative dental care services,” and was not protected by state action because it was “directly contrary to state law.” The case was settled in September 2023.

Conclusion

FTC Chairman Ferguson’s directive shows the agency will continue to prioritize labor markets in competition enforcement. Occupational licenses, particularly those advanced by professional associations, are a likely target of future enforcement actions.

The FTC should take advantage of the reform movement currently underway at the state level by continuing to advocate for changes to occupational licensing regimes. Moreover, the agency should study how professional associations heighten barriers to entry through increased occupational licensing requirements.