Insight

March 6, 2024

FTC to Test New Merger Guidelines in Kroger/Albertsons Challenge

Executive Summary

- On February 26, 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and nine state attorneys general sued to block the $24.6 billion merger between supermarket chains Kroger and Albertsons; Colorado and Washington had already filed suits to halt the deal.

- The FTC contended that the merger would lead to higher prices for groceries and eliminate competition for unionized grocery store workers.

- The lawsuit will serve as an important test case for several themes outlined in the Merger Guidelines recently published by the FTC and Department of Justice in December 2023.

Introduction

On February 26, 2024, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and nine state attorneys general sued to block the $24.6 billion merger between supermarket chains Kroger and Albertsons. The action followed lawsuits filed by Colorado and Washington, also seeking to block the deal.

The FTC claimed that the merger would lead to higher prices for groceries, lower quality products and services, and limit choices for consumers. Furthermore, the agency asserted that the merger would eliminate competition for unionized grocery store workers.

In December 2023, the FTC and the Department of Justice (DOJ) jointly published new Merger Guidelines. These guidelines provide insights into how the agencies evaluate mergers in the context of antitrust law. The lawsuit against Kroger and Albertsons will serve as an important test case for several themes outlined in the Merger Guidelines. Many of the concepts pulled from the Merger Guidelines included in the FTC’s complaint reflect the agency’s more aggressive approach to antitrust enforcement.

The FTC’s Complaint

The FTC alleged that the merger of Kroger and Albertsons would substantially lessen competition in supermarkets, resulting in higher grocery prices, lower quality of goods and services, and fewer choices for consumers.

In the press release announcing the merger challenge, FTC Bureau of Competition Director Henry Liu stated that “this supermarket mega merger comes as American consumers have seen the cost of groceries rise steadily over the past few years,” and asserted that the merger would “lead to additional grocery price hikes for everyday goods.”

Immediately noticeable is how the FTC conflated individual prices and inflation. Inflation is the general rise in all prices and happens when overall demand outstrips supply, not simply the rise in price of individual goods and services. This misunderstanding is consistent with the Biden Administration’s handling of elevated inflation over the past three years, during which it has proposed policies to address individual prices rather than all prices.

The FTC also claimed that the 700,000 workers employed by the two companies will be harmed by the merger. The agency alleged that competition between the two companies to hire and retain workers through collective bargaining agreements with local unions has resulted in higher wages, better benefits, and improved working conditions for employees, and that the merger would threaten the ability of these workers to negotiate such advantageous employment contracts.

When the merger was announced, Kroger and Albertsons pledged to divest 413 stores and other assets across 17 states and the District of Columbia to C&S Wholesale Grocers. These divestitures were made to address any antitrust concerns by the FTC. Yet the agency was unconvinced that the divestitures would prevent a substantial lessening of competition in supermarkets.

Relevant Product Market

Supermarkets

The FTC identified traditional supermarkets and supercenters as the relevant market, and referred to this market in the complaint as “supermarkets.”

The agency stated that supermarkets “offer consumers convenient ‘one-stop shopping’ for food and grocery products.” Supermarkets “typically have a broad and deep product assortment of tens of thousands of stock-keeping units…in a variety of package sizes, as well as a deep inventory of those items.” It added that “supermarkets are large stores that typically have at least 10,000 square feet of selling space.”

Notably absent from the relevant market definition were warehouse clubs such as Costco, limited assortment stores such as Aldi, premium natural and organic stores such as Whole Foods, dollar stores, and e-commerce retailers such as Amazon. The reason for the FTC’s exclusion of each varied somewhat, but ultimately amounted to how these stores offered a “differentiated customer experience.” Meanwhile, other organizations including the North American Industry Classification System – which standardizes business classifications used by federal statistical agencies – consider warehouse clubs and supercenters as part of the same market.

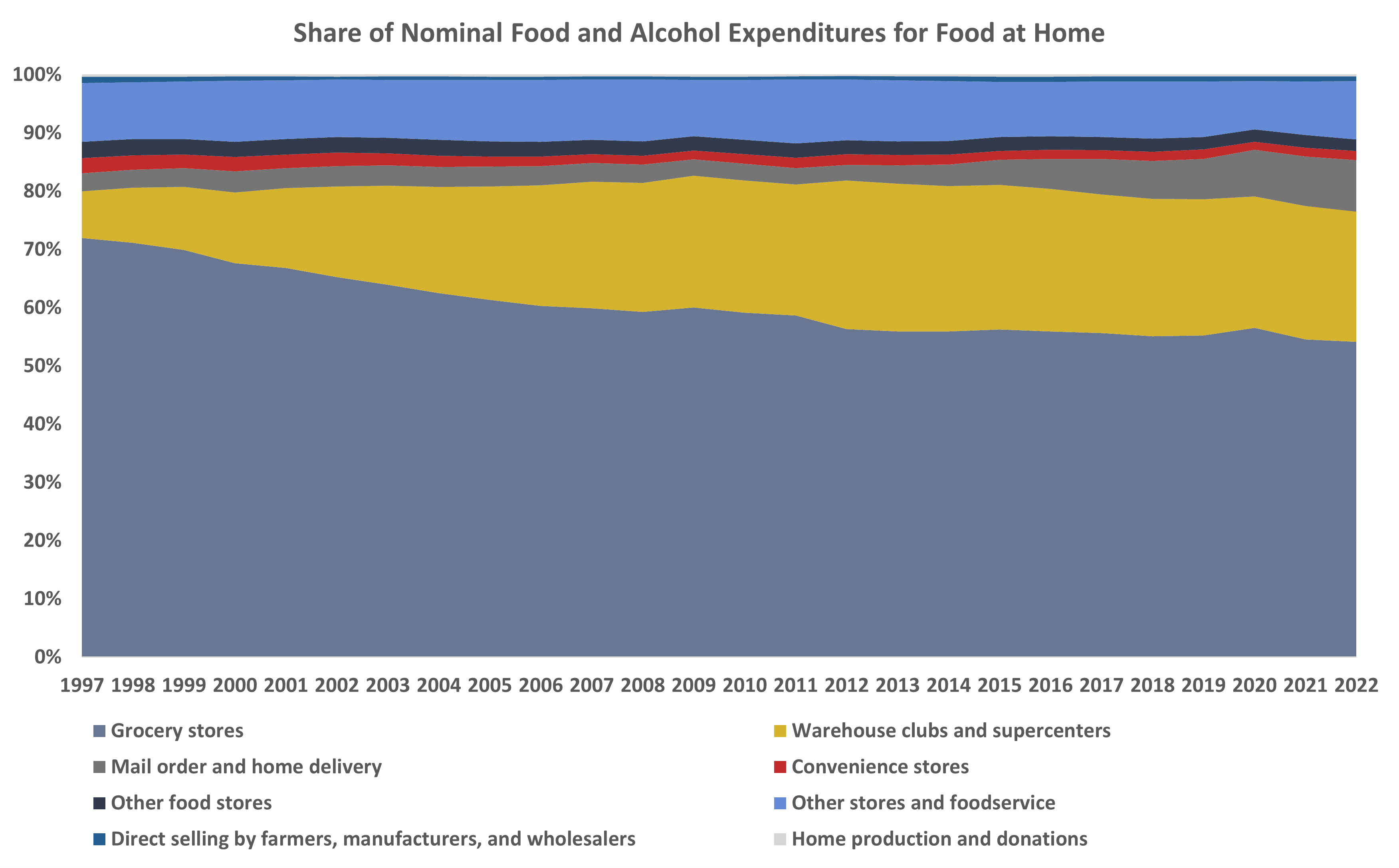

Data from the Department of Agriculture (USDA) suggest that the FTC is excluding a sizable share of the market in its analysis. In 1997, 72 percent of nominal food and alcohol expenditures for food at home were made at grocery stores, while only 8 percent were made at warehouse clubs and supercenters. By 2022, that ratio narrowed to 54 percent of food at-home expenditures made at grocery stores, a drop of 18 percentage points, and 22 percent at warehouse clubs and supercenters, an increase of 14 percentage points.

Figure 1

*Source: USDA Food Expenditure Series

In 2017, before becoming FTC chair, Lina Khan – along with Sandeep Vaheesan, a colleague at the Open Markets Institute – conceded that the rise of warehouse clubs was putting competitive pressure on grocery stores. They wrote that “a wave of grocery mergers and buyouts in the 1990s, coupled with entry by warehouse clubs and discount general merchandise stores into grocery products, reshaped the landscape. Grocers sought to bulk up in order to compete with the scale of warehouse clubs and large discount stores.” The FTC’s decision to exclude warehouse clubs from the analysis directly conflicts with the competitive environment of grocery store sales.

During that same span between 1997–2022, a new competitor emerged. Mail order and home delivery for food at home increased from 3 percent of expenditures to 9 percent. Results from a USDA survey offered further evidence of continued growth. The survey found that nearly “2 in 10 (19.3 percent) U.S. residents who regularly shopped for groceries did so online at least once in the last 30 days.” Moreover, among those who did, “44.7 percent purchased groceries online 3 or more times.” While still in its infancy, this market promises to change the competitive dynamics among supermarkets, supercenters, and warehouse clubs in the future.

Restricting the relevant market to supermarkets represents a static view of competition for grocery sales that does not reflect a decades-long reconfiguration in market participants and ignores changes in consumer preferences that have broadened the scope of competitors.

Geographic Location

The FTC made clear that the national market was insufficient to measure competitive effects. The agency claimed that “customers prefer to purchase grocery products at retailers near where they live or work. Supermarket competition therefore primarily occurs locally.”

This claim is consistent with research from the USDA which found that while consumers lived an average of 2.2 miles away from the nearest supermarket, their primary store was 3.8 miles away. The data suggest that consumers are willing to travel beyond the nearest supermarket to better match their preferences. Excluding certain market participants and applying a narrow geographic market may lead to an overestimate of market concentration.

Merger Guidelines Will Also Be on Trial

In December 2023, the FTC and DOJ jointly published new Merger Guidelines to replace the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines and the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines. The document consists of 11 different guidelines. Guidelines 1–6 describe the “frameworks the Agencies use to identify that a merger raises prima facie concerns, and Guidelines 7–11 explain how to apply those frameworks in several specific settings.”

While these guidelines do not have the force of law, they provide antitrust practitioners, the business community, and the courts insight into how the agencies assess mergers in the context of antitrust law. The new Merger Guidelines reflect a more aggressive approach to merger enforcement and depart from the unifying consideration of market power and its effect on consumers. This previous chief consideration, highlighted in the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines, acted as the limiting principle of enforcement. The new Merger Guidelines afford the agencies opportunities to broaden their considerations for antitrust enforcement beyond the welfare of consumers to include labor, small competitors, and other stakeholders.

The Merger Guidelines introduced several new ideas and adjusted concepts that existed in previous iterations of the guidelines. The FTC’s Kroger and Albertsons merger challenge promises to test several of these changes. Ultimately, the courts will decide the validity of these ideas and determine whether they are consistent with antitrust law.

Guideline 1: Mergers Raise a Presumption of Illegality When They Significantly Increase Concentration in a Highly Concentrated Market

Among the most notable changes to the Merger Guidelines was the lowering of concentration thresholds in which the agencies would presume a merger illegal. The Merger Guidelines outline two thresholds that would trigger a structural presumption of illegality: 1) A post-merger Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) measure of concentration – a commonly used measure of market concentration calculated by summing the squares of each firm’s market share – greater than 1,800 and a change in HHI greater than 100, and 2) a merged firm’s market share greater than 30 percent and a change in HHI greater than 100.

Comparatively, the HHI threshold in the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines was 2,500 and an increase of 200. Furthermore, the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines explained that “market shares may not fully reflect the competitive significance of firms in the market or the impact of a merger. They are used in conjunction with other evidence of competitive effects.” Conversely, the new Merger Guidelines establish a structural presumption based on the HHI irrespective of the measure’s limitations.

Using the new thresholds, the FTC alleged that the merger is “presumptively illegal in overlapping local markets surrounding more than 1500 Kroger and Albertsons supermarkets.” The agency listed 17 local markets that exceed the new thresholds.

The FTC did not specify the HHI level for the 17 markets in question. The FTC will need to convince the courts that the new HHI levels are consistent with economic reasoning and law, especially if they fall below the concentration thresholds established, and accepted by the courts, in the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines.

Guideline 7: Trend Toward Concentration/Guideline 8: Serial Acquisitions

In Section I of the complaint, the FTC claimed that “Kroger and Albertsons acquired their massive size through numerous mergers over the past three decades, part of a broader trend of significant consolidation in the United States grocery industry.” Section III listed the seven acquisitions made by Kroger between 1983–2015 and the five made by Albertsons between 1998–2016. Guidelines 7 and 8 discuss trends toward concentration and serial acquisitions.

Guideline 7 outlines the framework for “when an industry undergoes a trend toward consolidation,” and explains that “the Agencies consider whether it increases the risk a merger may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly.” A trend toward consolidation alone, according to Aviv Nevo, Director of the FTC’s Bureau of Economics, and Susan Athey, Chief Economist for the DOJ Antitrust Division, is not a basis for a challenge on its own but is considered a “plus factor” in the analysis.

The FTC and DOJ assert that “recent history and likely trajectory of an industry can be an important consideration when assessing whether a merger presents a threat to competition.” While this notion is to be viewed through the lens of Guidelines 1–6, it underlines the agencies’ concern with market structure rather than market power and its effect on consumers. Industries consolidate for a wide variety of reasons, including competition from imports, failing firms, and new technologies. That the number of players in a market is decreasing says very little about the competitive environment. It may pose a challenge to convince the court that expanding the scope beyond the merger in question is relevant to the analysis.

Relatedly, Guideline 8 states that “the Agencies may evaluate the series of acquisitions as part of an industry trend or evaluate the overall pattern or strategy of serial acquisitions by the acquiring firm collectively.”

Guideline 8’s inclusion was designed to address roll-up strategies often employed by private equity firms. This tactic involves numerous, and often small, acquisitions in a particular industry. Chair Khan has been vocal about combatting roll-up strategies and the history of the agency’s underenforcement. In a September 2023 opinion piece, Chair Khan stated that “roll-ups are executed through a series of smaller acquisitions, in which each may fall below the dollar threshold that triggers reporting to federal antitrust agencies.” Considering past acquisitions is a departure from traditional enforcement practice in which the agency focused on the competitive effects of the merger in question.

Guideline 10: When a Merger Involves Competing Buyers, the Agencies Examine Whether It May Substantially Lessen Competition for Workers, Creators, Suppliers, or Other Providers

The FTC identified a second relevant market in its challenge to the Kroger and Albertsons merger: union grocery labor. The FTC stated that Kroger and Albertsons are the two largest employers of union grocery workers in the United States and that the two firms “monitor wages and benefits set at local competitors, including each other, and often attempt to match or exceed competing wage and benefit offers.” The agency added that “Kroger and Albertsons also try to poach grocery workers from each other.”

Guideline 10 extends the concept of monopsony power – a market with one buyer – beyond its effects on sellers to include its effect on labor markets. While effects on labor have been considered in other antitrust cases, it is the concept’s first formal inclusion in the guidelines.

The agency alleged that the merger would eliminate this competition and likely lead to “lower wages and reduced benefits, opportunities, and quality of workplace conditions and protections.” The FTC defined the union grocery worker labor market as “local areas subject to the [collective bargaining agreements].” The agency listed four states, each including a subset of smaller locations, in which the merger is considered presumptively illegal using the HHI framework.

Guideline 10 explained that “the level of concentration at which competition concerns arise may be lower in labor markets than product markets” and that “labor markets can be relatively narrow” given their characteristics. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that 4.5 percent of those employed in retail trade – which includes supermarkets – were represented by unions. It is difficult to envision a situation in which firms competing for labor at a local unionized supermarket do so without considering the wages and benefits provided to local non-unionized labor.

Divestitures

Divestitures have been a prominent feature in supermarket mergers. The FTC claimed, however, that the “hodgepodge of 413 stores and other castoff assets across 17 states and the District of Columbia to C&S Wholesale Grocers…does not solve the competitive issues created by the proposed acquisition.”

The FTC alleged that the proposed divestiture package “lacks the scale and necessary assets…that [Kroger and Albertsons] rely on today to successfully operate their respective businesses.” Moreover, the agency added that C&S, the proposed buyer of the divested assets, has “limited supermarket operating experience” and “is a poor choice for a divestiture buyer and increases the likelihood that the divested stores will flounder or fail.”

This stance reflects the agency’s skepticism of negotiating remedies despite an agency retrospective that found overwhelming success in maintaining or restoring competition in the relevant market.

Conclusion

The FTC’s opposition to the Kroger and Albertsons proposed merger contains several objections typically found in traditional antitrust analysis viewed through the lens of market power and its effect on consumers. It does, however, depart in some noticeable ways.

These departures reflect recent changes to the antitrust agencies’ Merger Guidelines. The FTC’s suit relies, in part, on a structural presumption of illegality resulting from lowered concentration thresholds and features the labor market as a prominent reason for condemning the merger. It also referenced past mergers in its suit and a trend toward consolidation in the industry, rather than independently analyzing the merger in question.

Courts will consider the validity of these novel claims and determine whether the new Merger Guidelines should inform future antitrust jurisprudence.