Insight

May 2, 2022

Funding Ukraine’s Defense and the Outlook for the National Defense Budget

Executive Summary

- On March 16, President Biden signed the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) of fiscal year (FY) 2022, which set a $782 billion defense budget for the year.

- The CAA legislation also included an additional $13.6 billion in emergency funding for security assistance to Ukraine.

- On March 28, the Biden Administration released the FY2023 President’s Budget, which included an $813 billion request for national defense.

- On April 28, in response to Russia’s ongoing war on Ukraine, President Biden requested an additional $33 billion in emergency defense, economic, and humanitarian assistance funding.

- Assuming the $33 billion supplemental funding is approved, total, new defense assistance to Ukraine in FY2022 would amount to $46.6 billion, while the need for follow-on assistance will necessarily be dictated by the course of the conflict.

Introduction

On February 24, Russian President Vladimir Putin launched another invasion of the sovereign nation of Ukraine – a significant escalation in a conflict that began with the Russian annexation of Ukrainian Crimea in 2014. The United States has played a leading role in marshalling global opposition to the invasion and has contributed billions of dollars in defense assistance to Ukraine. Relatedly, President Biden signed into law the full-year appropriations actions for fiscal year (FY) 2022. This marks the first enactment of annual agency funding since the expiration of the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), which imposed caps on discretionary spending levels through 2021. Congress enacted increases to the caps on defense and non-defense funding five separate times, most recently and finally with the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2019 (BBA), signed into law in August of 2019. For FY2022, Congress was unbound by the BCA, but nevertheless failed to reach timely agreement on discretionary spending levels until March, when President Biden signed into law appropriations acts that set the annual defense budget and provided Ukraine with emergency defense assistance. Congress must now consider an additional request for defense support for Ukraine, as well as defense funding levels for FY2023.

Recent Trends in Defense Funding

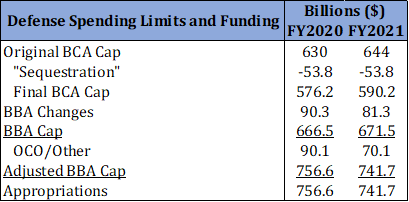

On August 2, 2019, President Trump signed into law the BBA of 2019, which established discretionary spending levels and enforcement provisions for FY2020 and FY2021. The act provided relief to both defense and domestic discretionary spending from spending caps put into place by the BCA of 2011.[1] The BBA set defense caps for FY2020 and FY2021 at $666.5 billion and $671.5 billion, respectively, and with allowances for adjustments to accommodate additional funding for overseas contingency operations (OCO) and emergencies. These revised caps reflect increases of $90 billion and $81 billion for FY2020 and FY2021, respectively, compared to the spending levels set forth under the BCA. For both FY2020, and FY2021, appropriations hewed to the caps established under the BBA (Table 1).[2]

Table 1: Status of Recent Defense Spending Limits and Appropriations

Defense Funding for FY2022 and Beyond

The BBA of 2019 covered the final two years of the BCA, after which the discretionary spending caps were no longer in force. While the BCA was a regular thorn in the side of congressional appropriators, it did facilitate a somewhat orderly mechanism for funding the agencies. Observers will note that several funding lapses did occur while the BCA was in force, but the disputes that animated those shutdowns were generally unrelated to funding levels, themselves. With the expiration of the BCA, funding federal agencies defaulted to the “regular” appropriations process. That process produced four continuing resolutions and did not resolve until nearly halfway through the fiscal year. Nevertheless, Congress avoided funding lapses and enacted full appropriations acts for the federal agencies, including the Department of Defense and related activities. Combined, the Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) of FY2022 provided $782 billion for national defense, plus an additional $7.5 billion in “emergency” defense funding, largely related to the withdrawal from Afghanistan.

In signing the CAA into law, President Biden also approved the Ukraine Supplemental Appropriations Act of 2022, which provided an additional $13.6 billion in emergency funding for defense assistance to Ukraine. The administration had previously relied on existing authorities to draw down funding and provide equipment for Ukraine’s defense. The tempo of operations in Ukraine has largely exhausted the $13.6 billion assistance, prompting President Biden to propose another $33 billion in supplemental defense, humanitarian, and economic assistance. The administration is seeking to enact this supplemental assistance to Ukraine along with additional funding related to COVID-19. These supplemental requests will likely occupy Congress for the next several weeks.

There have already been discussions among policymakers of needing a continuing resolution to fund the executive agencies, including those related to national defense at the conclusion of FY2022. The President’s Budget proposed an overall defense budget of $813 billion, of which $773 would be devoted to the Department of Defense. The budget request is informed by the National Security Strategy and National Defense Strategy. Classified versions have been reported to Congress but have not yet been made public. The outlook for follow-on Ukrainian defense assistance is necessarily unclear.

Conclusion

The past decade of defense funding was largely guided by incremental budget deals that provided some relief against the BCA’s discretionary spending caps. These deals were as much informed by demands for “parity” between defense and non-defense spending increases, irrespective of national security needs. The expiration of the BCA may have rendered that artifice obsolete but invites the challenges that have historically bedeviled the regular appropriations process. The “regular process” is less orderly than was the BCA, but if recent history is any guide, it may allow for legitimate national security considerations to better inform defense funding policy.

Appendix: Defense Funding History and The Evolution of the Budget Control Act, American Taxpayer Relief Act, and Sequestration

On August 2, 2011, the president signed the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA, P.L. 112-25). The BCA reimposed a regime of discretionary spending caps that had previously been in place through the 1990s and lapsed in 2002. The BCA provided a mechanism – a sequester, or an across-the-board rescission of budget authority – if those caps were breached.

The BCA also imposed an additional mechanism, variously referred to as the “Joint Committee Reductions,” “Automatic Spending Reductions,” or more colloquially just as the “sequester,” which was designed to reduce the deficit by $1.2 trillion (including interest costs) over and above the reductions imposed by the BCA discretionary caps. This mechanism was designed to come into force if the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, also referred to as the Super Committee, failed to produce a plan that reduced the deficit by equal measures. The committee failed to do so, thus triggering the automatic enforcement provisions of the BCA through FY2021. The BCA required OMB to issue a sequestration order on January 2, 2013, cancelling $109 billion in budget authority, split evenly between defense and non-defense categories, already enacted for FY2013 – a true sequester of budget authority already in place.[3] For FY2014–2021, discretionary savings result from spending caps lowered about $90 billion per year below the original BCA discretionary caps. Remaining savings would come from cancellation of mandatory budget authority through an annual sequestration order.[4]

On January 2, 2013, (effective for January 1), President Obama signed the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) of 2012, which addressed several major expiring provisions contributing to what was referred to as a “fiscal cliff.” Among these provisions was the sequestration set to take place on January 2. The BCA delayed these cuts by two months – pushing the order to March 1, 2013. It also reduced the amount to be sequestered to $85 billion, again split evenly between defense and non-defense funding.[5]

OMB issued a sequester order pursuant to ATRA on March 1, 2013, and cancelled $85 billion in enacted budgetary resources for the balance of the fiscal year. The order reduced defense funding by $42.6 billion, non-defense discretionary funding by $25.8 billion, and non-defense mandatory spending by $16.9 billion.[6]

Federal funding faced a troubled road in the remainder of 2013, including a partial government shutdown beginning October 1, 2013, owing to a failure between the House and Senate to agree to discretionary spending levels and other policy matters. On October 16, Congress passed a continuing resolution through January 15, 2014, that provided $986 billion in overall discretionary budget authority on an annualized basis for FY2014, and essentially extended FY2013 post-sequester defense spending at $518 billion on an annualized basis. Yet at this funding level and in the absence of a change to the BCA, defense spending would face a $20 billion sequester in January. This is because for FY2014, the lowered spending cap for defense was $498.1 billion.[7] The enactment of the BBA set forth defense spending limits in place for FY2014 and FY2015.

On November 2, 2015, President Obama signed into law the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA 2015), which established discretionary spending levels and enforcement provisions, for FY2016 and FY2017. The act provided relief to both defense and domestic discretionary spending from spending caps put into place by the BCA of 2011.[8] The BBA 2015 set defense caps for FY2016 and FY2017 at $548.1 billion and $551.1 billion, respectively, with allowances for adjustments to accommodate additional funding for OCO and emergencies. These revised caps reflect increases of $25 billion and $15 billion for FY2016 and FY2017, respectively, compared to the spending levels set forth under the BCA.

On February 9, 2018, President Trump signed into the law Bipartisan Budget Act of 2018 (BBA 2018). BBA 2018 set defense caps for FY2018 and FY2019 at $629 billion and $647 billion, respectively, again with allowances for OCO and other emergencies. These adjustments mark a $79.9 billion increase from the BCA limit for FY2018 of $549.1 billion and an $84.9 billion increase from the FY2019 limit of $562.1 billion.

[1] The spending caps in place under current law were imposed by the Budget Control Act, and essentially reflect two rounds of spending cuts: first by the imposition of initial spending caps put in place in 2011, plus further reductions subsequent to the failure of the Congressional “Super Committee,” to propose a deficit reduction plan of at least $1.2 trillion. The second rounds of cuts, shorthanded to “sequestration” imposes an annual $54 billion reduction in the defense funding caps. Thus, the current law caps were established pursuant to the BCA, they also reflect a fallback mechanism in the BCA that was not intended to take effect.

[2] https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/51873-Sequestration.pdf, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52704-sequestration.pdf, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/sequestration/sequestration_final_january_2016_potus.pdf, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/sequestration_reports/2017_final_sequestration_report_may_2017_potus.pdf, http://docs.house.gov/meetings/RU/RU00/CPRT-114-RU00-D001.pdf

[3] http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/09-12-BudgetControlAct_0.pdf

[4] ibid

[5] https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/American%20Taxpayer%20Relief%20Act.pdf

[6] http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/fy13ombjcsequestrationreport.pdf

[7] http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/sequestration/sequestration_update_august2013.pdf

[8] The spending caps in place under current law were imposed by the Budget Control Act, and essentially reflect two rounds of spending cuts: first by the imposition of initial spending caps put in place in 2011, plus further reductions subsequent to the failure of the Congressional “Super Committee,” to propose a deficit reduction plan of at least $1.2 trillion. The second rounds of cuts, shorthanded to “sequestration” imposes an annual $54 billion reduction in the defense funding caps. Thus, the current law caps were established pursuant to the BCA, they also reflect a fallback mechanism in the BCA that was not intended to take effect.