Insight

November 30, 2018

Future Risks Confronting the Multiemployer Pension System

Executive Summary

- The multiemployer pension system faces projected net liabilities, or underfunding, of $638 billion.

- With the passage of time, more and more plans are expected to fail, risking an increasing number of beneficiaries’ retirement and bankrupting the system’s federal insurer.

- While difficult to quantify, increasing stresses on plans and relatedly on sponsors may lead to a chain reaction of failures with knock-on budgetary and economic consequences.

- These dynamics suggest that the cost of federal intervention will only grow with time if the system is left unreformed.

Introduction

Multiemployer pensions are collectively bargained defined benefit retirement plans. There are about 1400 such plans covering 10 million active and retired workers. Many of these plans are critically underfunded, risking the retirement benefits of covered workers. Meanwhile, the federal backstop for such plans – the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation or PBGC – doesn’t have the resources to protect retirees if the multiemployer-pension system’s finances continue to deteriorate.

While past its statutory deadline, Congress’s Joint Select Committee on Solvency of Multiemployer Pension Plans is reportedly still considering policy options for addressing these challenges. In doing so, policymakers will need to strike a balance between shoring up the system as a whole, careful stewardship of taxpayer dollars, and the risk that possible pension losses pose to current and future retirees. There is a risk that the Committee will fail to produce any meaningful reforms. Unfortunately, the cost of that failure to retirees and likely to taxpayers will only grow over time.

The Multiemployer Pension Economy

According to the PBGC, there were 1,375 multiemployer defined-benefit pension plans with 10,565,000 participants in 2017.[1] More detailed information is available for 2015. Of the roughly 10 million-plus participants, 36.1 percent were active participants and 35.5 percent were retired, while 28.4 percent are separated participants either receiving or eligible to receive benefits.

The net income of the multiemployer plans has already gone negative, with a total of $44.3 billion in expenses and only $39.7 billion in income in 2015. This shortfall is a significant deterioration from the prior year, when the net income of the plans was positive ($24 billion).[2]

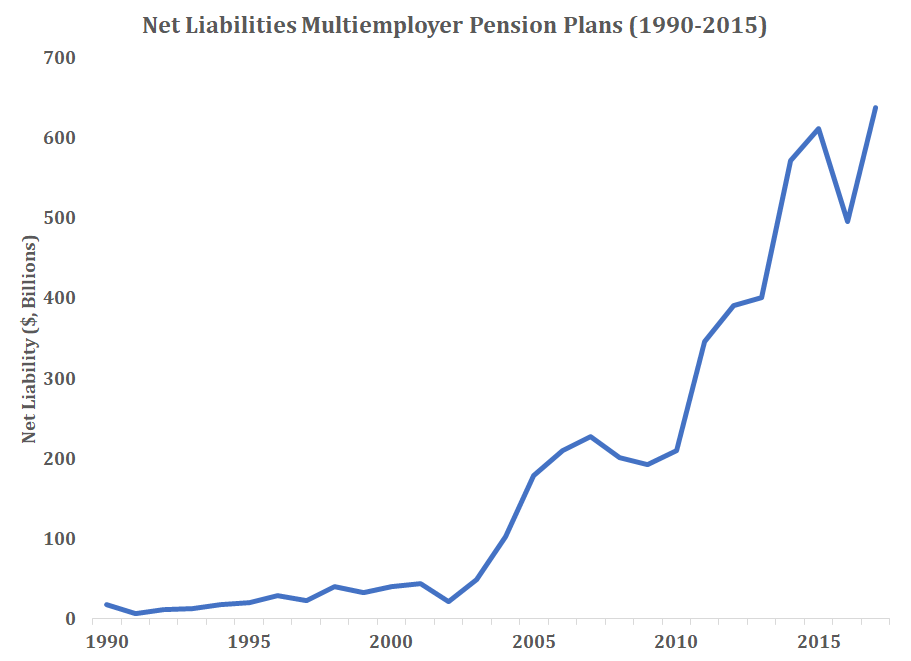

Figure 1: Trends in Multiemployer Pension Plan Funding 1990-2015

Collectively, these plans held $478 billion in assets, but faced $1.116 trillion in liabilities as of 2015. Accordingly, the multiemployer pension system faces projected net liabilities, or underfunding, of $638 billion.

According to the PBGC, 56 percent of participants and 63.8 percent of plans met the statutory requirements for being in the “green zone,” which is considered to be “not in distress,” based on reported funding levels. About 1.3 million current or future retirees in about 130 plans, however, are in “critical and declining” plans that are projected to become insolvent in 15-20 years and face projected net liabilities of $100 billion.[3]

The Federal Backstop

The PBGC Multiemployer Program insures the benefits for multiemployer plan participants. Given the large projected liabilities confronting the multiemployer system, including the more near-term projected insolvencies of critical and declining plans, the Multiemployer Program is projected to become insolvent as well.

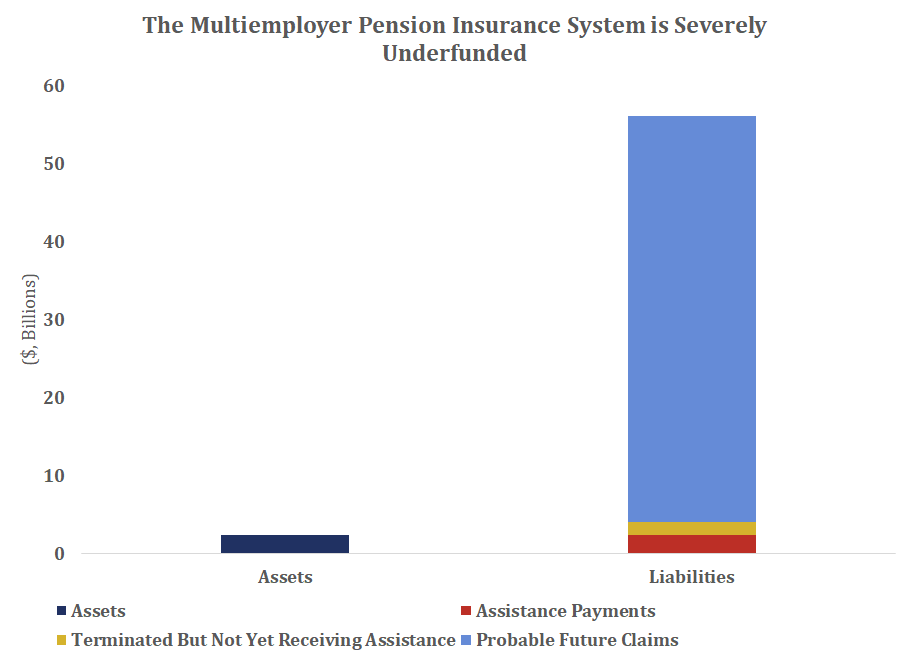

Figure 2: Present Value Liabilities Outstrip Assets

At present, the Multiemployer Program reported assets of $2.3 billion to cover $56.2 billion in liabilities for 184 plans.[4] The liabilities are composed of three categories. First, 78 plans are currently receiving payments from PBGC, the present value for which is about $2.4 billion. 64 plans have terminated but have not yet started receiving financial assistance payments from PBGC, the present value for which is estimated to be $1.7 billion. The last and most consequential category of projected liabilities are from the 42 plans that are ongoing (i.e., have not terminated), but which PBGC projects will deplete their assets and require financial assistance within 10 years. The present value of future financial assistance payments for these 42 ongoing plans is $52 billion.

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that the PBGC will face a cash shortfall of $34 billion from 2017 through 2036, between insurance claims filed with the program and the available resources to meet these claims.[5] In particular, a 2016 CBO projection stated that in 2017–2026, the PBGC’s multiemployer program would receive claims of $9 billion while collecting premiums of $4 billion and interest of $1 billion, thus resulting in a $4 billion shortfall. At current projections, the PBGC multiemployer pension plan program will deplete its accumulated assets and become insolvent in 2025. If this happens, projections indicate that around $3 billion in claims will not be paid to beneficiaries in 2025 and 2026. In 2027–2036, claims by insolvent plans to the PBGC are projected to increase to around $35 billion.

In general, the basic picture of the principal federal guarantor of multiemployer pensions reflects the underlying system: Potential claims vastly outstrip dedicated resources. Significantly, the costs and the scale of the problem worsen with time.

Contagion and Multiemployer Pensions:

Partially animating concern for the health of the overall multiemployer pension system is the possible risk of “contagion.” The contagion argument as applied to multiemployer pensions states that a failure of a multiemployer plan or a major contributing employer could cause the failure of other multiemployer plans in which the affected employers also participate. The exact scope of the economic risk is difficult to pinpoint, but cascading failure could pose potential economic risks over and above the direct pension losses retirees may experience.

Contagion would most likely occur due to the insolvency of a relatively large, systematically significant, plan. If such a plan were to become insolvent, it has the potential to adversely impact the contributing employers and their participation in other plans. No significantly large plan has yet gone insolvent. There are, however, several that are projected to go insolvent within the next decade.

Another different but related type of contagion may result when the failure of an employer that contributes to more than one plan leads to the failure of multiple plans. This second type of contagion would most likely be the result of the failure of a company that is a dominant employer in multiple plans. For example, suppose an employer were assessed withdrawal liability.[6] This could lead the employer to go out of business. If such an employer contributes to any other plans, it would likely be unable to continue contributing to these other plans. If the employer is a major contributing employer to these other plans, they would be at risk of collapse as well.

The financial solvency of a number of existing multiemployer plans depends on only a handful of contributing employers who also contribute to several other plans. If one of the large employers were to exit a plan that depends on a small number of employers to provide a significant share of the contributions being made to the plan, it would significantly and negatively impact the plan.

The Risk of Contagion is Non-Zero, But Difficult to Quantify

Because the significant risks to the multiemployer system, including the projected plan failures that drive the PBGC’s estimated liabilities and CBO’s related analyses, are prospective, there is no direct empirical evidence to support the concern for contagion. In addressing this concern, however, the current director of the PBGC recently testified that the risk is “plausible,” as were potential contagion risks posed by the failure of a large plan sponsor.[7]

A proxy for the risk posed by possible contagion would reflect the significance of these plans to the overall economy, and the risk of cascading plan failure. Both are highly difficult to estimate credibly. A multiemployer pension advocacy group estimated costs to the federal government from projected pension plan failures that ran into the hundreds of billions of dollars in the 10-year budget window, but that estimate does not appear to have been replicated elsewhere.[8]

More specifically, one recent study assessed the possible effects from the likely failure of The Central States Pension Fund.[9] Central States is the fourth largest multiemployer plan by number of participants and the largest in terms of benefit payments. Central States represents the largest of the multiemployer pension plans in critical and declining status. An August 2018 report by Matrix Global Advisors projected that if the Central States fund failed in 2025, the year it is projected to become insolvent, it would cost the United States over 55,000 jobs, more than $5 billion in lost economic activity, and more than $1.6 billion in state, local, and federal tax revenue. Given the interconnectedness among multiemployer pension plan contributors, the study notes, there is a significant possibility of a contagion effect. Thus, a failure of the Central States may trigger other multiemployer plan insolvencies.

Conclusion

The multiemployer pension system has been in predictable decline for a number of years. At present, the system faces projected net liabilities, or underfunding, of $638 billion. As time passes, these liabilities will come due and increasingly outstrip available resources. Plan failures, or even the failure of a large sponsor itself, may lead to a chain reaction of failures with knock-on budgetary and economic consequences. This cascade effect is an important consideration for policymakers weighing potential federal intervention. As unpalatable as many of the available policy options are, they are likely only to get less appealing with time.

[1] https://www.pbgc.gov/sites/default/files/2016_pension_data_tables.pdf

[2] https://www.dol.gov/sites/default/files/ebsa/researchers/statistics/retirement-bulletins/private-pension-plan-bulletins-abstract-2015.pdf

[3] https://www.pensions.senate.gov/sites/default/files/PBGC_Testimony-Joint_Select_Committee_on_Solvency_of_Multiemployer_Plans-5.17.2018.pdf; Note: There is a legitimate concern that even “green zone” plans are inadequately funded, but that discussion is not examined in this piece.

[4] https://www.pbgc.gov/sites/default/files/pbgc-annual-report-2018.pdf

[5] https://www.cbo.gov/publication/51536

[6] https://www.uschamber.com/testimony/testimony-employer-perspectives-multiemployer-pension-plans

[7] https://www.pensions.senate.gov/sites/default/files/PBGC_Testimony-Joint_Select_Committee_on_Solvency_of_Multiemployer_Plans-5.17.2018.pdf

[8] http://nccmp.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Michael-Scotts-Remarks-to-2018-NCCMP-Annual-Conference.pdf

[9] http://getmga.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/The-Crisis-Facing-Multiemployer-Pension-Plans-August-2018.pdf