Insight

March 4, 2025

High Egg Prices Lead to Accusations of Market Power: Unscrambling the Economics

Executive Summary

- In a post depicting empty grocery store egg shelves on X last month, Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya suggested producers could be exercising market power to reap ill-gotten profits by keeping prices elevated.

- The most recent bout of avian flu – first detected in late 2021 – has sent egg prices surging 53 percent since January 2024 and over 80 percent since January 2022 as more than 150 million chickens have been culled.

- While the FTC could expend its limited resources investigating the perceived market power of egg producers, the laws of supply and demand offer a more plausible and straightforward explanation for the increased prices.

Introduction

Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya recently posted a picture of empty egg shelves on the social media platform X and suggested producers could be exercising their market power to extract ill-gotten profits by keeping prices elevated. In follow-on posts, Bedoya criticized the newly minted FTC Chairman Andrew Ferguson for not investigating the matter as egg prices have surged 53 percent since January 2024 and 80 percent since the most recent bout of the avian flu began wiping out a significant share of the egg-laying population.

The most recent outbreak of the avian flu, first identified in late 2021, caused significant supply-side disruption. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that 166 million wild aquatic birds, commercial poultry, and backyard or hobbyist flocks have been affected. The New York Times reported that “more than 30 million chickens – roughly 10 percent of the nation’s egg-laying population – have been killed in just the last three months.”

While the FTC could use its limited resources to investigate the market power of egg producers, the laws of supply and demand could provide a more plausible and straightforward explanation for surging egg prices.

Commissioner Bedoya’s Social Media Posts

On February 16, 2025, FTC Commissioner Alvaro Bedoya posted a photo of empty egg shelves on the social media platform X.

Figure 1

The post was one in a series that suggested producers could be manipulating the market to keep supply low, and prices elevated, to boost profits. Bedoya also criticized FTC Chairman Andrew Ferguson stating, “There’s a person in the government who could flick his pen and start an investigation into what the hell is going on with eggs. His name is Andrew Ferguson. He’s the new head of the FTC. Has he done it? No.”

The post prompted a response from Chairman Ferguson, in which he noted that egg prices had soared during the prior FTC leadership’s tenure, and they had done nothing.

Price and Supply of Eggs

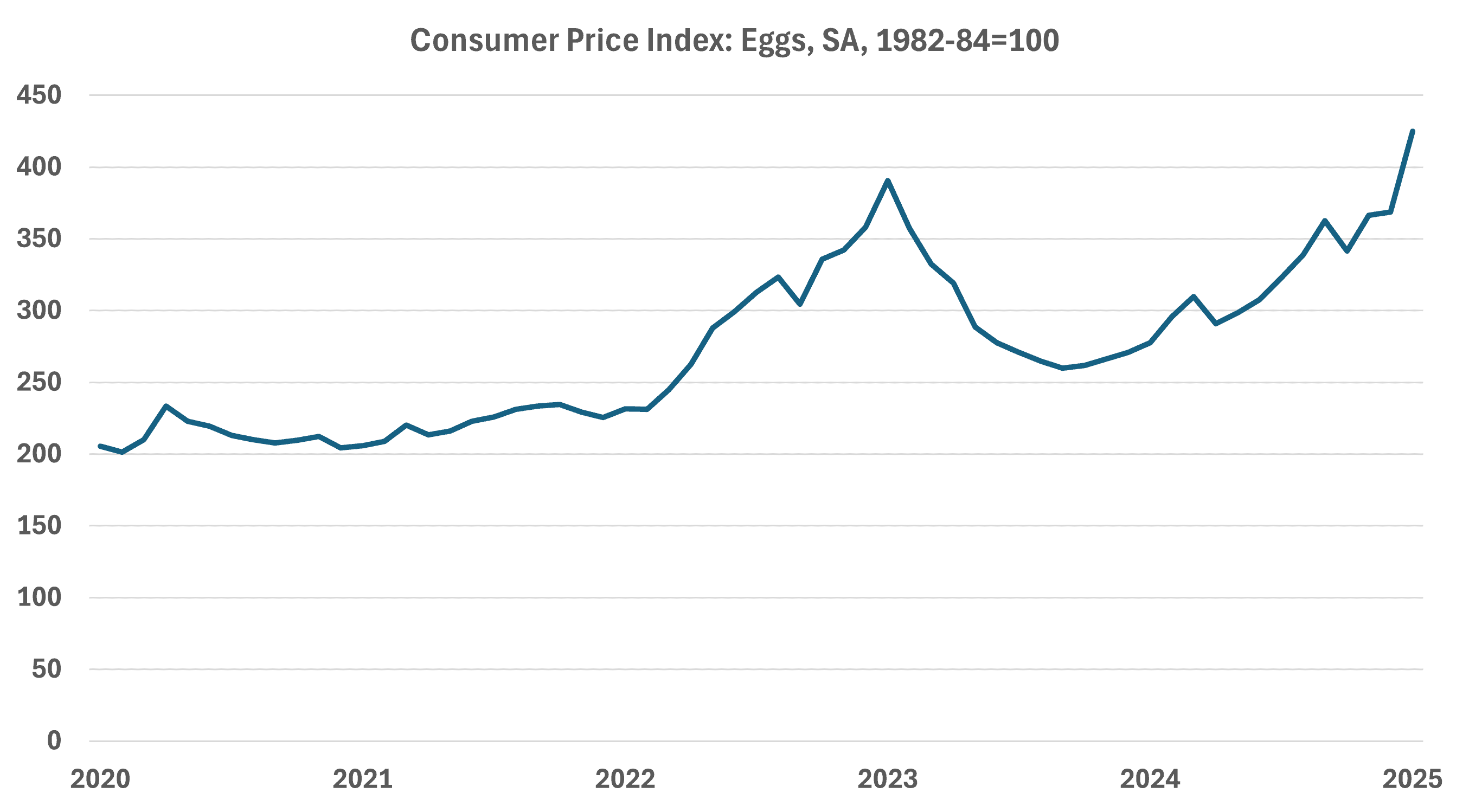

The Bureau of Labor Statistics Consumer Price Index report showed that egg prices have increased 84 percent since January 2022 when the avian flu was first detected and 53 percent over the last 12 months (Figure 2).

Figure 2

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics

The Market for Eggs

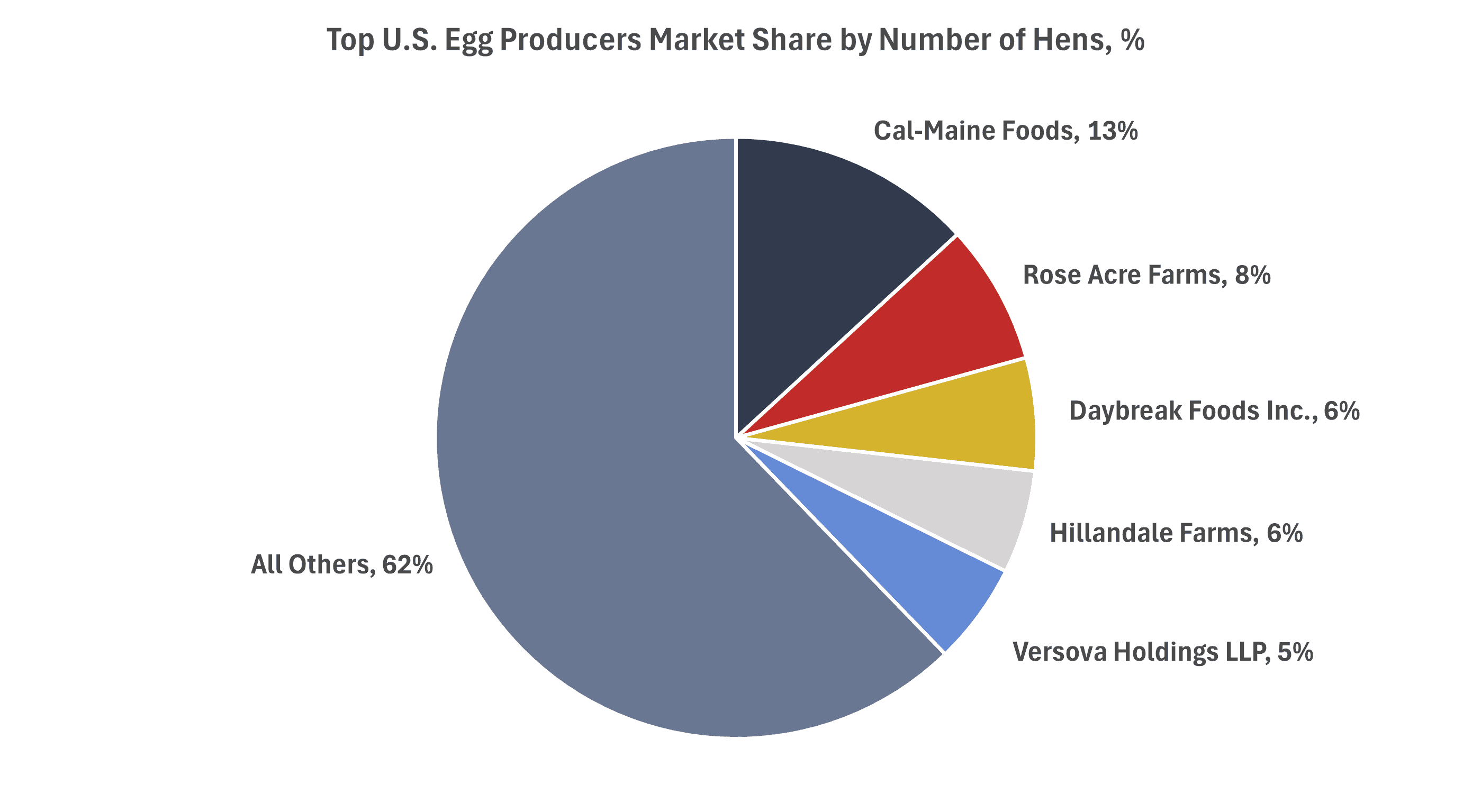

WATTPoultry published data on the 63 largest U.S. egg producers in 2024, measured by the size of their layer flock – which are hens specifically raised for egg production – at the end of 2023. The American Action Forum (AAF) found that the top five producers own approximately 40 percent of the layer flock, with the largest producer owning about 13 percent. Using these data as a proxy for egg production, AAF estimated that the industry’s Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) – a commonly accepted measure of market concentration – is 445. An HHI of 445 suggests an unconcentrated market according to the 2023 Merger Guidelines.

Figure 3

Laws of Supply and Demand

In his posts, Commissioner Bedoya stated that egg production “appears to be only modestly down from before the pandemic in 2021,” suggesting that prices should not have spiked so significantly.

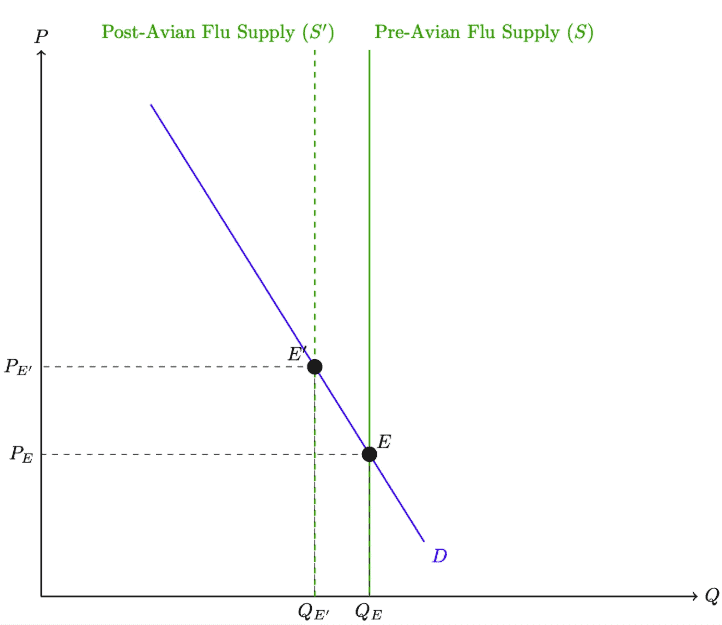

Economist Brian Albrecht – who posted a blog discussing Bedoya’s claims – offered an economic rationale for why even a small change in egg production could yield such a large change in price. Albrecht concluded that the “size of the price change depends on both supply AND demand elasticities, which are about how easily the quantity supplied and quantity demanded respond to price changes.” Citing a previous estimate of supply and demand elasticities from the last episode of avian flu, Albrecht explained that “egg demand elasticity is -0.15, meaning a 1% increase in price only reduces quantity demand by 0.15%. Put differently, if the quantity supplied drops by 1%, prices will rise by about 6.67%.” In other words, the quantity demanded for eggs is not sensitive to price increases.

Demand for eggs is inelastic because the good lacks substitutes. Consumers will continue to buy eggs even when prices rise.

In the short term, the supply curve for eggs is vertical as it is difficult to quickly replenish the egg-laying birds infected or slaughtered to prevent the spread of avian flu. Albrecht explained that because of the vertical supply curve, “any leftward shift of supply (from avian flu losses) results in the same quantity reduction but potentially huge price increases,” as seen in Figure 4.

Figure 4

Source: Stop blaming rising egg prices on market power, Brian Albrecht

Albrecht also cast doubt over Bedoya’s claim that increased profits could be evidence of market manipulation by producers. He provides a hypothetical scenario in which there are 100 egg producers, and the avian flu wipes out 50; he finds that the remaining producers would see their profits rise because the market price rose while costs did not change.

Albrecht’s economic reasoning is a much more plausible explanation for surging egg prices than market power. It is more likely that the reduced supply – largely driven by the length of time it takes to replenish the laying flock – and the inelasticity of the supply and demand curve resulted in higher prices than market power.

Import Relief

To help balance the effects of the domestic supply shock, the private sector has turned to imports. Shortly after the avian flu outbreak began, imports spiked (Figure 5). Moreover, CNN reported that U.S. businesses plan to import more than 420 million eggs from Turkey in 2025.

Figure 5

Source: https://dataweb.usitc.gov/trade/search/Import/HTS, HTS code: 040721

Regulatory relief could also be on the near-term horizon. Secretary of Agriculture Brooke L. Rollins published an opinion piece in The Wall Street Journal outlining the Trump Administration’s plan to lower egg prices. Among the remedies discussed, Rollins stated that the administration “will consider temporary import options to reduce egg costs in the short term.” Neither Rollins’ commentary, nor a related press release from the Department of Agriculture (USDA), provided specifics. Neither Rollins’ commentary, nor a related press release from the USDA provided specifics.

Yet Rollins qualified that these options would only be considered if “we determine that doing so won’t jeopardize American farmers’ access to markets in the future.” Moreover, the USDA press release noted that the agency would “explore options for temporarily…decreasing exports.” Both statements suggested that the administration is seeking more involvement in the management of the domestic supply of eggs while protecting farmers at the expense of consumers facing higher prices for eggs.

The temporary nature of the unspecified import options could limit their effectiveness at mitigating the impact of future supply shocks. Businesses are unlikely to adjust long-term business plans knowing that any relief from new imports will be temporary.

Conclusion

The outbreak of avian flu in late 2021 sent the prices of eggs soaring over 80 percent and 53 percent in just the last 12 months.

FTC Commissioner Bedoya suggested that sky-high egg prices could be the result of market power and called upon the FTC to investigate. It is more likely that the reduced supply – largely driven by the length of time it takes to replenish the laying flock – and the inelasticity of the supply and demand curve were the culprits behind higher prices, rather than market power.