Insight

May 29, 2023

Highlights of the Fiscal Responsibility Act

Executive Summary

- The Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 provides for an increase in the federal debt limit, suspends the federal debt limit until January of 2025, and puts restraints on certain elements of nondefense discretionary spending.

- The Act’s primary distinguishing feature is the reimposition of enforceable discretionary spending caps for fiscal years 2024 and 2025 that will save over $200 billion in the first two years.

- Other elements of the Act include modest reforms to certain social safety net programs, a new administrative PAYGO regime, as well as rescissions of certain COVID-19 funding provisions.

Introduction

In January of 2023, Secretary Yellen informed Congress that the United States had reached its statutory debt limit and would need to exercise its “extraordinary authorities” to ensure that the Treasury Department would have sufficient cash to pay the nation’s obligations. The communication set off a negotiation between, primarily, the House of Representatives and the White House. That negotiation culminated in the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, which provides for an increase in the federal debt limit and suspends the federal debt limit until January of 2025. In addition, the Act includes a number of policy changes, including reforms to certain benefit programs, a mechanism for constraining administrative actions, and renewed discretionary spending caps.

Spending Caps and Budgetary Provisions

In exchange for suspending the debt limit until January of 2025, The Fiscal Responsibility Act imposes spending caps for fiscal years (FY) 2024 and 2025. These are essentially a renewal of the cap regime imposed by the Budget Control Act, which expired in 2021.

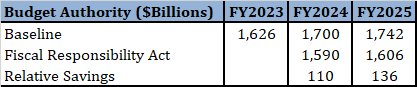

Figure 1. Spending Caps

Under the Act, base defense funding would be set at $886 billion for FY2024 and $895 billion for FY2025. Non-defense funding would be capped at $704 billion and $711 billion for FYs 2024 and 2025, respectively. Combined, the Act would cap base discretionary funding at $1,590 billion and $1,606 billion, respectively. Members of Congress and the administration have made public claims as to the relative savings. But those estimates are necessarily relative to a given baseline, and the respective branches of government maintain their own baseline estimates. Compared to CBO’s non-emergency, base discretionary funding of $1,700 and $1,742 for FYs 2024 and FY2025 (adjusted to remove certain, non-base funding), respectively, the Act would save $110 billion in the first year of the caps, and $136 billion in the second. This bill reflects a departure from the dubious “parity principle” that informed past appropriations deals, which required that defense spending increases be matched by non-defense increases. Additionally, the Act contains a mechanism that will reduce the discretionary caps by one percent if Congress fails to enact all 12 appropriations bills by January of 2024.

Beyond FY 2025, the enforceable caps expire, and are supplanted by spending limits that are designated as discretionary spending levels for the purposes of a Congressional Budget Resolution. The Act establishes reduced spending levels over the subsequent four fiscal years, but notably, these levels are not enforceable through sequestration as is the case for spending levels imposed under the statutory caps operative in FYs 2024 and 2025.

The Act also contains 81 rescissions of unspent budget authority for certain programs that received funding during the COVID-19 pandemic. These rescissions reportedly amount to a $28 billion reduction in funding, though until CBO provides a cost estimate, it is unclear how much spending would ultimately be forgone. Additionally, the Act rescinds $1.4 billion from the Internal Revenue Service’s new funding received under the Inflation Reduction Act. According to news reports, the White House and congressional Republicans agreed to a deal whereby $20 billion in funding would be repealed outside of this bill. This will likely allow for an additional $20 billion in discretionary spending under the caps.

Additional Policy Changes

The Fiscal Responsibility Act includes a number of additional policy changes that include modest reforms to the student loan program, the Temporary Assistance to Needy Families (TANF) program, and the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Programs (SNAP). The Act would end the current student loan repayment pause 60 days from the date the Act becomes law. Under TANF, states can receive credit for caseload reductions, as measured against certain levels. The Act would update the reference period to 2015 from 2005, which may incrementally reduce caseloads. With respect to SNAP, the Act increases the age of exemption from work requirements on able-bodied recipients without children from 50 to 55, phased in over three years. This change sunsets in 2030, however, and was also paired with broadened work requirement exemptions for the homeless, veterans, and others that may leave the program’s beneficiary population unchanged.

Somewhat outside of fiscal policy, the Act includes two provisions that seek to improve the nation’s regulatory environment. First, the Act includes the Administrative Pay-As-You-Go Act, which imposes new reporting requirements on the director of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and agency heads. Among other elements, the new policy would require that agency heads must submit an estimate of the effects on direct spending from a potential discretionary administrative action. If administrative action would have the effect of increasing spending, the agency head must submit to OMB a proposal to offset that spending increase with administrative actions. Notably, this new policy expires at the end of 2024, and it provides the OMB director with authority to waive the new requirements. Last, the Act includes modest permitting reforms that would allow for the designation of a lead federal agency as part of the environmental review process required for major energy-related projects. In addition, the Act would require that such reviews should take no longer than two years.

Conclusion

By far, the most significant policy change in the Fiscal Responsibility Act is the suspension of the debt limit until January of 2025. That policy change forestalls a potential default, the consequence of which would far outweigh the effects of any of the Act’s other policy changes. Nevertheless, the Act will, relative to current projections, save hundreds of billions in taxpayer funds, and modestly improves other federal policies.