Insight

December 20, 2022

Highlights of the FY2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act

Executive Summary

- The fiscal year 2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) provides $1.7 trillion in discretionary funding for federal agencies.

- The bill includes just over $85 billion in combined supplemental funding for disaster recovery efforts and support for the defense of Ukraine.

- The bill provides an increase of $69.3 billion for the Department of Defense, and somewhat departs from the practice of matching defense increases with non-defense increases.

- The CAA also includes additional policy changes, including to the process for presidential elections, retirement policy, and most significantly from a budgetary perspective, the deferral of a $138 billion funding cut due to Statutory Pay-As-You-Go.

Introduction

Fiscal year (FY) 2023 began on October 1, but as has become routine, Congress had failed to enact full-year funding laws for federal agencies. Rather, Congress relied on temporary measures – continuing resolutions – to fund agencies. The most recently enacted continuing resolution expires Friday. There was some doubt as to whether Congress could find agreement on discretionary spending levels given that the House will have a new majority next year, but just in time for the holidays, a deal appears to have been reached to enact all 12 appropriations bills. That $1.7 trillion in appropriations is crammed into a sprawling 4,000-plus page omnibus in the waning days of the year with little time for review, and with unrelated policy measure hitching a ride is, again, typical. In general, the FY2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA) provides somewhat less non-defense discretionary funding than the current congressional majority would have enacted, while providing a significant boost to defense. The omnibus also includes supplemental funding of $38.2 billion and $47.3 billion for disaster recovery efforts and support for the defense of Ukraine, respectively. The bill also includes reforms to the elections law and retirement policy. Perhaps the most consequential element of the omnibus, at least in budgetary terms, is the deferral for two years of a hypothetical $138 billion in spending cuts that were scheduled to take effect early next year.

Funding Levels

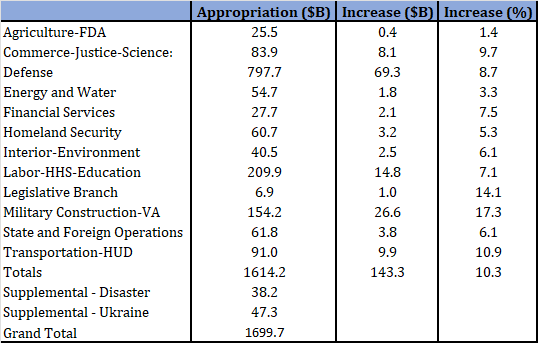

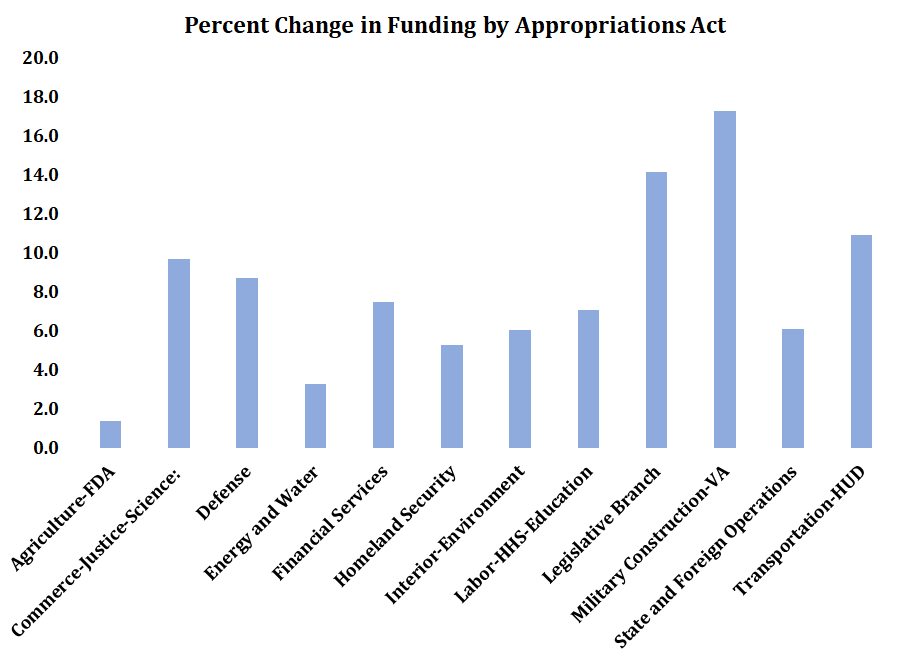

On Wednesday, Senate Appropriations Committee Chairman Patrick Leahy released the FY2023 Consolidated Appropriations Act, which provides full-year funding for federal agencies. Enactment of full-year appropriations is increasingly a holiday-season exercise. This year, midterm elections and the resultant change in majorities in the House of Representatives in the next Congress animated some of the delay, as did basic policy differences related to defense and non-defense funding levels. According to the Senate Appropriations Committee, the CAA will provide about $1.6 trillion in base discretionary funding, which is about $140 billion more than was enacted for FY2022, roughly a 10 percent increase.

The key policy debate that held up this spending deal was on the relative funding for defense and non-defense activities. This bill reflects somewhat of a departure from the dubious “parity principle” that informed past appropriations deals, which required that defense spending increases be matched by non-defense increases. The CAA provides a significant boost to Department of Defense (DoD) funding specifically, both over current law, and over the president’s request. According to the Appropriations Committee, overall defense funding, which includes activities outside of DoD, is $858 billion, which would mean that more than two-thirds of the discretionary increases are devoted to defense.

It is important to note, however, that there are some inconsistencies in how these increases are characterized by the appropriations committees. Ideally, members would debate each appropriations act, as well as amendments, and provide the budget agencies, members, and the public with an opportunity to scrutinize the acts. One distressing element of the current approach to federal funding coincides with the return of earmarks. Enacting massive omnibus acts obscures the thousands of “congressionally directed” spending projects, the new term for what has often been understood to be pork-barrel projects. This latest CAA is a classic example, and is brimming with at least 3,000 earmarks totaling more than $5 billion.

Supplemental Elements

In addition to funding normal federal operations or “base discretionary funding,” the CAA includes two supplemental spending provisions. The first would provide $38.175 billion in emergency funding to provide for relief and recovery efforts necessitated by hurricanes, tornadoes, flooding, and wildfires that occurred over the course of the year. In terms of funding, the largest recipients of this supplemental are the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s Disaster Relief Fund ($5 billion), the Department of Agriculture’s Farm Disaster Assistance ($3.7 billion), Housing and Urban Development’s Community Development Block Grant Disaster Recovery Grant Program, ($3 billion) Department of the Interior ($2.43 billion), U.S. Forest Service ($2.056 billion), Health and Human Services ($1.75 billion), the Environmental Protection Agency ($1.668 billion) and the Army Corps of Engineers ($1.4 billion).

The supplemental also includes additional funding to support Ukrainian defense efforts against the Russian invasion. In total, the Ukrainian supplemental provision provides $47.332 billion in funding for military and humanitarian assistance. Of this amount, over $27 billion is devoted to direct security assistance to Ukraine, as well as replenishment of U.S. munitions production, among other security assistance provisions. The balance of the funding is devoted to humanitarian assistance such as food and refugee assistance. The provision also provides funding for energy supplies.

Policy Changes

End-of-year spending deals are often referred to as Christmas trees, such that every special interest in Washington can hang its policy ornament on them before the legislation reaches the president’s desk. This particular tree is somewhat less glittery than initially hoped for by some members and leaves out a major tax package, immigration reforms, and other policy changes. Three major policy elements did make it into the CAA, however. First, the bill includes the Electoral Count Reform Act, which would update the 1887 Electoral Count Act governing presidential elections. The act would clarify some statutory elements in the process and reduce ambiguities in the roles of federal and state officials in the process.

Second, the CAA includes the SECURE 2.0 Act. The bill is a follow-on measure to the First SECURE Act, which itself follows a long line of retirement policies enacted by now-Senators Ben Cardin and Rob Portman. The act contains a number of changes to the tax treatment and eligibility for retirements benefits. It would expand auto enrollment in retirement plans while providing businesses with assistance in establishing retirement plans for employees. It would expand the Saver’s Credit, and also allow for credit for employers matching contributions for those making student loan payments. For older workers, the bill would increase the age at which individuals must begin taking mandatory distributions from their existing plans.

Finally, the CAA builds on past congressional practice and punts a major spending cut for two years. Under current law, largely due to the American Rescue Plan Act, there is a $742 billion positive balance on the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go (S-PAYGO) scorecard. All else equal, this would mean that early next year the president would be required to order a sequestration of $742 billion. There is nowhere near that much funding eligible for sequestration under current law, however, meaning the actual cut would be closer to $138 billion—but even that appears to be too much deficit reduction for congressional appetites. Congress has thus deferred this spending cut until 2025, at which point the theoretical cut would be about $1.5 trillion.

Conclusion

An unfortunate tradition in Congress has played out yet again. With just days until funding for the federal government expires, Congress will likely enact with little scrutiny a $1.7 trillion funding package into law. There is no formal cost estimate available for the legislators or the public to get an objective view of the budget effects of the potential new law, and there is precisely zero chance the public has had the time to carefully scrutinize the bill and related report language in totality. There are some meaningful policy improvements, but in general, the CAA reflects the worst tendencies in the modern Congress.