Insight

September 9, 2021

Highlights of the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act

Executive Summary

- The Infrastructure and Investment Jobs Act was passed by the Senate in August and awaits action in the House, reportedly until the chamber acts on a forthcoming reconciliation bill.

- The arcane budgetary treatment of certain transportation spending masks the true cost of the bill, which could be as high as $400 billion over the next decade.

- With a substantially higher share of the Act financed through borrowing, the value proposition of the Act is somewhat lower than if it were efficiently financed.

Introduction

On August 10, the Senate passed the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act, the formal name for the Bipartisan Infrastructure Framework (BIF), which was supposed to be a paid-for infrastructure investment measure. The reality is somewhat different from the advertising, however. The Act is far from paid-for, which in turn undermines the economic rationale for infrastructure spending. Somewhat obscuring the cost is the arcane budgetary treatment of certain transportation spending. Indeed, the Act authorizes $191.5 billion in new spending that is not reflected in the deficit effects of this bill. While investment in infrastructure can be productivity-enhancing, which can mitigate cost, it is not a “free lunch.” As laudable as bipartisan legislating may be, its products are rarely good for the budget, and this Act is no different.

Budgetary Considerations

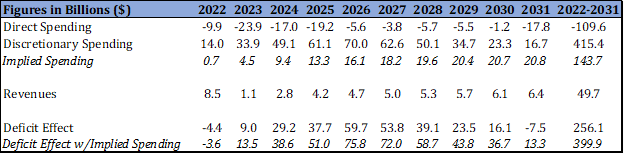

The Act authorized, on net, $68 billion in direct or mandatory funding for infrastructure projects, but according to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), these authorizations would correspond with a net reduction in direct spending of more than $109 billion over the next decade. This seeming disconnect emanates from one of the most maddening federal budget concepts, which treats the funding (contract authority) and resulting spending (outlays) for transportation projects differently from all other mandatory spending. Indeed, the most conspicuous aspects of the Act – new spending on roads, highways, and other transportation – don’t “count” in this bill. Rather, the Act authorizes the new spending, but the outlays associated with the new funding are within the purview of the Appropriations committees, meaning the costs associated with new spending won’t show up until the Appropriators write bills to spend their new, higher allowance. In total, the Act provides $196.5 billion in new contract authority for spending on surface and transit transportation projects. The actual spending associated with this new funding, using CBO’s spendout model, would amount to about $143.7 billion over the next 10 years. Combined with the $415.4 billion in additional spending estimated to emanate from the Act, and netted against the $49.7 revenue offsets, the Act would increase the deficit by $399.9 billion over the next decade.

Economic Considerations

The reality of this Act differs somewhat from the textbook exercise that informs the value proposition of public spending on infrastructure. Fundamentally, infrastructure investment passes the (economic) cost-benefit test when, on net, the productivity effects of the new investment exceed the costs. Painting every highway in America my favorite color, for instance, would likely fail this balancing test. Federal investment in intermodal freight projects, on the other hand, would likely pass. The benefits that accrue to the economy in the form of improved productivity will reflect the degree to which those dollars spent on infrastructure genuinely improve productivity. The Act would seed both kinds of projects. It is not, fundamentally, just a physical infrastructure bill, but includes billions in new spending on myriad projects across many sectors. The evidence suggests that, broadly, infrastructure spending more often than not contributes to productivity. But with Congress involved, well less than 100 percent of this bill is in core, productivity-enhancing projects. So, the gross benefits of the Act are somewhat dilute compared to the ideal. But one must also examine the financing mechanism.

Just borrowing more to finance spending is a loser, according to CBO. The benefits of high-quality infrastructure investment can indeed outstrip the costs, but it can be a close call. Financing public investment with tax policies that particularly affect private investment, for example, fails that cost-benefit test. According to CBO, the Act is financed with a patchwork of familiar budget offsets that fall well short of fully covering the cost. It is possible that a mix of borrowing and contemporaneous offsets can finance infrastructure that offers a positive value proposition, but that is jeopardized by the substantial borrowing implied by this Act.

Conclusion

The Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act advertised a significant “investment” in America’s infrastructure. Infrastructure is very much in the eye of the beholder, and the Act funds myriad projects through multiple federal departments and agencies. To the extent this spending is on projects that do not enhance productivity, the more the financing matters in assessing the cost-benefit proposition offered by the Act. Unfortunately, the Act relies, as is increasingly the case, on borrowing. While the Act’s sponsors are to be commended for pursuing a bipartisan approach to addressing a major policy challenge, the final product, awaiting House attention, falls somewhat short of its initial promise.