Insight

September 21, 2023

Industry Concentration Is the Wrong Way To Judge Meatpacking Mergers

Executive Summary

- In September, Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) introduced the Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement for Meatpacking Act which would establish concentration thresholds to define a merger or acquisition in the meatpacking industry deemed a monopoly and considered in violation of antitrust law.

- While the bill aims to prevent the meatpacking industry from further consolidation, it risks blocking potentially procompetitive mergers by ignoring the limitations of industry concentration measures in assessing competitive effects.

- Current antitrust laws and provisions in the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 are sufficient to protect consumers from mergers and acquisitions among meatpackers where the effect is market power that results in consumer harm.

Introduction

On September 14, 2023, Senator Josh Hawley (R-MO) introduced the Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement for Meatpacking Act aimed at clarifying the definition of a merger to monopoly to prevent further consolidation in the meatpacking industry. The bill would amend the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 and establish specific market concentration thresholds as the sole determinant in deeming a merger a monopoly and therefore in violation of antitrust law, a prescription that aligns with the concerns of the Biden Administration that the industry is overly concentrated. The bill’s introduction closely followed Tyson Foods’ announcement that it will close two poultry plants in Missouri, a third in Arkansas, and a fourth in Indiana.

Measures of industry concentration are limited in their ability to assess competitive effects. For more than 40 years, antitrust enforcers – the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) – understood these limitations and reserved concentration measurements as the initial screen in the merger evaluation process. The agencies would supplement industry concentration measures with other, more economically rigorous analysis focused on market power. In other words, the agencies were more concerned with a merged firm’s ability to raise prices, reduce output, or otherwise harm consumers.

Current antitrust law governing mergers and acquisitions and provisions in the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 are sufficient to protect consumers from mergers in the meatpacking industry where the effect is market power. The proposed legislation would likely result in blocking potentially procompetitive mergers.

Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement for Meatpacking Act

The Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement for Meatpacking Act would amend the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 to clarify which mergers or acquisitions are to be considered a monopoly, and therefore illegal. The meat of the act “establish[es] specific thresholds for market concentration, allowing federal antitrust authorities to more effectively prohibit or unwind acquisitions that concentrate the meatpacking sector.”

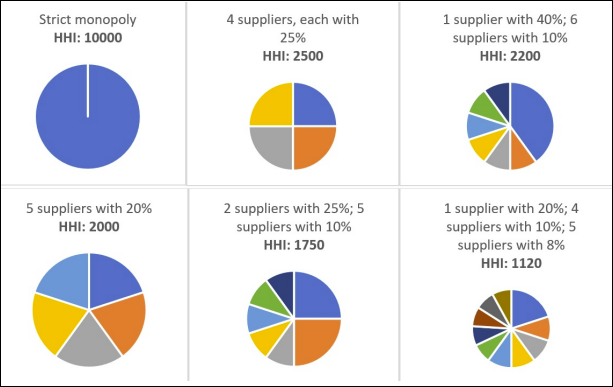

Using the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) as the measure of market concentration, the bill proposes a post-merger or acquisition threshold of 1,800 or an increase in the HHI of more than 100 in any relevant market be “deemed to create a monopoly,” and therefore illegal.

The concentration thresholds in the bill align with those proposed in the FTC and DOJ’s jointly published draft Merger Guidelines (dMG). Guideline 1 of the dMG creates the same structural presumption where a post-merger HHI greater than 1,800 and a change in HHI over 100 will be considered by the agencies to be in violation of the antitrust laws.

In addition to preventing prospective mergers, Senator Hawley’s press release indicated that the bill should make enforcement more effective in unwinding acquisitions already consummated. The language of the text provides no such parameters for enforcement, however. Omitting any guidance from the bill could leave businesses unsure of whether the antitrust agencies will attempt to unwind mergers already completed.

Limitations of Measures of Market Concentration

For more than 40 years, antitrust enforcement has focused on protecting the welfare of consumers from market power. This means that antitrust enforcers block mergers where the effect is higher prices, reduced output, or other harm to consumers. The Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement for Meatpacking Act breaks from this enforcement principle.

Using a measure of market concentration as the determining factor in defining a merger to monopoly is insufficient to explain whether the merged firm has market power. This notion was included in the DOJ and FTC’s jointly published 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines (2010 HMG) (actively being revised by the agencies) in which the agencies warned that “market shares may not fully reflect the competitive significance of firms in the market or the impact of the merger” and that they are to be “used in conjunction with other evidence of competitive effects.” See the American Action Forum’s analysis of the 2010 HMG.

Several former antitrust agency chief economists concluded that “it is unhelpful (and may be actively misleading) to simply measure the relationship between HHI and price in an industry and use that relationship to try to predict future price effects, in merger analysis in particular,” and that “most economists today agree that more concentrated markets are not always less competitive than less concentrated markets” They add that “in some markets, competitors are more efficient at higher levels of scale, meaning that competition among a small number of large firms may be more vigorous than competition among a large number of smaller businesses.”[i]

This reality is why antitrust enforcers, over the last 40 years, have been skeptical in relying solely on market concentration as a predictor of anticompetitive harm.

Figure 1 shows several examples of market structures and HHIs.

Figure 1

*Image taken from Antitrust: Principles, Cases, and Materials

To illustrate the flaws of using market concentration to determine competitive effects, consider the example from Figure 1 of two suppliers each with 25 percent market share, five suppliers each with 10 percent market share, and a pre-merger HHI of 1750. If two of the firms with a 10 percent market share merged to yield a combined market share of 20 percent, the post-merger industry would have an HHI of 1950 and a change in HHI of 200. Such a transaction would be deemed illegal as proposed in the Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement for Meatpacking Act, though it is unlikely that such a merger would have anticompetitive effects. Conversely, the merger could enable the merged firm with a 20 percent market share to be more competitive with the two larger firms still in the market.

According to the Biden Administration, the four largest beef-packing firms control 82 percent of the market. Assuming an equally divided market of these four firms (with 20.5 percent each), the bill would prevent the two remaining firms with a combined market share of 18 percent from merging. The post-merger HHI would increase from 1843 to 2005, a difference of 162. Both the level and change in the HHI would exceed the threshold, though it is difficult to imagine a market with four dominant firms and two small firms being more competitive than five firms with similar market shares. This is likely a prime example of the notion presented by the economists in which “in some markets, competitors are more efficient at higher levels of scale, meaning that competition among a small number of large firms may be more vigorous than competition among a large number of smaller businesses.”

While the examples are simplified, so too is using market concentration as a proxy for market power. Focusing simply on the number of actors in a market ignores the potentially procompetitive effects of such a merger.

Section 7 of the Clayton Act and Packers and Stockyards Act

Current antitrust legislation, as well as provisions in the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921, are sufficient to prevent mergers that pose anticompetitive harm to consumers.

Section 7 of the Clayton Act is the primary statute governing mergers. The law prevents mergers and acquisitions where the “effect of such acquisition may be substantially to lessen competition, or tend to create a monopoly.” As described in the example, it is unlikely that such a merger violates Section 7, yet it would exceed the market concentration thresholds of the proposed bill and would therefore be deemed illegal.

Limiting the merger criteria to a measure of market concentration robs the merging parties of a more thorough assessment of the proposed merger. The agencies employ econometric tools that enable them to quantify whether the merged firm would be able to exercise market power in the form of higher prices, reduced output, or pose other harm to consumers.

Furthermore, the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 was signed into law to “assure fair competition and fair trade practices, to safeguard farmers and ranchers…to protect consumers…and to protect members of the livestock, meat, and poultry industries from unfair, deceptive, unjustly discriminatory and monopolistic practices.”

Section 202 of the Packers and Stockyards Act outlines unlawful practices. Using language similar to the Sherman Act, another cornerstone of antitrust law, it prohibits practices where the effect is price fixing or manipulation, restraining commerce, or creating a monopoly.

Conclusion

While the Strengthening Antitrust Enforcement for Meatpacking Act aims to prevent further industry consolidation, it would undermine the very complex merger evaluation process undertaken by the antitrust agencies. Current antitrust laws and provisions in the Packers and Stockyards Act of 1921 are sufficient to protect consumers from mergers and acquisitions among meatpackers where the effect is market power. The proposed legislation attempts to oversimplify this process and risks blocking potentially procompetitive mergers.

[i] Antitrust: Principles, Cases, and Materials, page 58-59; the conclusion is based on Nathan Miller et al., On the Misuse of regressions of Price on the HHI in Merger Review, 10 J. Antitrust Enforcement 248 (2021); and Steven Berry, Martin Gaynor & Fiona Scott Morton, Do Increasing Markups Matter? Lessons from Empirical Industrial Organization, 33. J. Econ. Persp. 44 (2019); Lenoard W. Weiss, The Structure-Conduct-Performance Paradigm and Antitrust, 127 U. Pa. L. Rev. 1104 (1979)