Insight

March 4, 2021

Lowlights of CBO’s Long-Term Budget Outlook 2021

Executive Summary

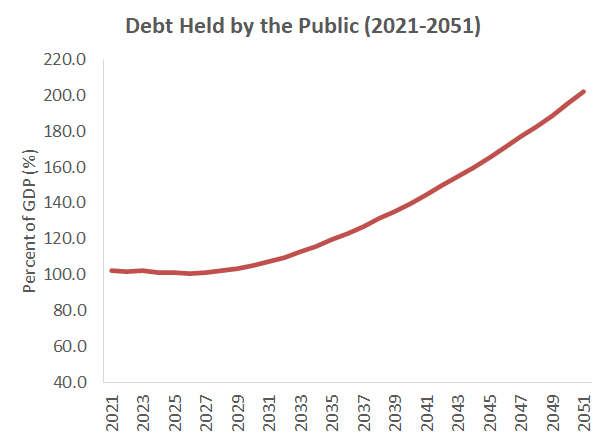

- According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), debt held by the public will reach 202 percent of gross domestic product in 2051.

- This report essentially confirms CBO’s September update, which indicated that the COVID-19 pandemic has given rise to substantial borrowing, but the long-term fiscal trajectory of the United States remains a function of long-standing budgetary pressures.

- Before long, stabilizing the debt will require an unprecedented fiscal consolidation.

The Long-Term Budget Outlook

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) released its updated Long-Term Budget Outlook and projected that the U.S. debt will essentially double as a share of the economy by 2051, rising from the current level of 102 percent to 202 percent of gross domestic product (GDP). This report, coming just 5 months after CBO’s last update, is largely unchanged and reflects the substantial deterioration in the nation’s fiscal outlook – already troubled – due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Figure 1

Over the medium term, increased projected deficits necessarily reflect the economic effects from and federal response to the pandemic. But over the longer term, the debt outlook remains driven by demography (which hasn’t changed since the last Long-Term Budget Outlook), the nation’s major entitlement programs (which are also unchanged), and growing interest on the nation’s ever-larger debt portfolio.

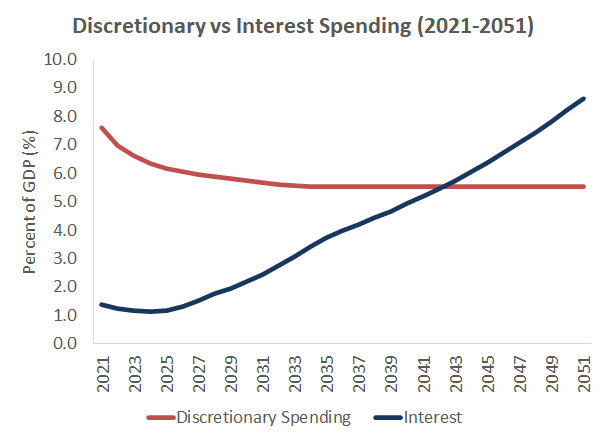

The long-term outlook reaffirms a trend in the nation’s finances, as Figure 2 illustrates. Despite continued markdowns in interest rates, debt service costs will crowd out other federal expenditures, and in 2043 these costs will exceed all other discretionary programs – defense, education, infrastructure – combined.

Figure 2

CBO has also previously calculated what is essentially the cost of delaying needed fiscal consolidation, shown in Figure 3. As the long-term outlook is substantially unchanged from CBO’s previous estimate, these calculations remain useful for characterizing the magnitude of fiscal consolidation to achieve debt stabilization goals. To hold debt held by the public as a share of GDP to about current levels, 100 percent, in 2050 would require an annual reduction (relative to CBO projections) in the primary deficit (a revenue increase, spending decrease, or both, excluding net interest) of 2.9 percent if begun in 2025. Achieving the same level of debt in 2050 would require a much larger fiscal consolidation if delayed until 2030 or 2035.

Figure 3

The same story holds true if the United States were to return to its 2019 debt level of 79 percent of GDP. It would require annual savings of 3.6 percent if begun in 2025, but 4.4 percent if begun in 2030. In both instances, achieving the necessary deficit reduction to achieve fairly modest debt targets in 2050 would be difficult if begun now, but would be more than 50 percent more painful if delayed for 10 years. For context, the magnitude of fiscal consolidation contemplated in any of these scenarios significantly dwarfs all but one historical tax increase. Essentially, this challenge would require deliberate fiscal consolidation on an unprecedented scale.