Insight

March 19, 2020

New Developments for Industrial Loan Companies: A Primer

New Developments for Industrial Loan Companies: A Primer

Executive Summary

- A new rule proposed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) codifies its approach to the management of industrial loan companies (ILCs), although the rule does not in and of itself make an industrial loan company charter any easier to obtain.

- Designed to provide very limited lending support to a market commercial banks were not serving, some ILCs have since morphed into large-scale financial services firms with activities rivalling that of commercial banks, although they do not need to be owned by banks and therefore are not regulated as banks by the Federal Reserve.

- This new rule did not give any indication that the FDIC would be lifting the moratorium it set on new ILC applications in 2006, so it was surprising that a day after this rule the FDIC announced that it had approved two new ILCs.

Context

On March 17, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) unanimously approved a proposed rule that would “codify existing practices” used by the FDIC in managing the industrial loan companies (ILCs) that it supervises. This proposed rule was closely followed on March 18 by news that the FDIC had approved ILC charters for fintech company Square and student loan servicer Nelnet, the first new charters since 2006. What, then, is an ILC, and why is this subject a source of considerable controversy in the United States?

History and Legal Framework

ILCs, also known as industrial banks, emerged in the early 1900s as a source of funding for industrial workers and other wage earners with moderate incomes, to whom traditional commercial banks were at the time not willing to offer uncollateralized loans. Industrial banks were always intended to provide only a fraction of the services that traditional banking provides, broadly acting as lenders but not as deposit-takers (deriving their funding solely from the issue of investment certificates). Industrial banks nonetheless dominated the consumer credit market for the middle classes for most of the 1920s and 1930s until traditional commercial banks expanded their consumer lending businesses.

Industrial banks have always been state-chartered, but one incidental impact of the 1982 Garn-St. German Depository Institutions Act was to make industrial banks eligible for the first time for FDIC deposit insurance, bringing these banks under the regulatory and supervisory authority of both their state and the FDIC.

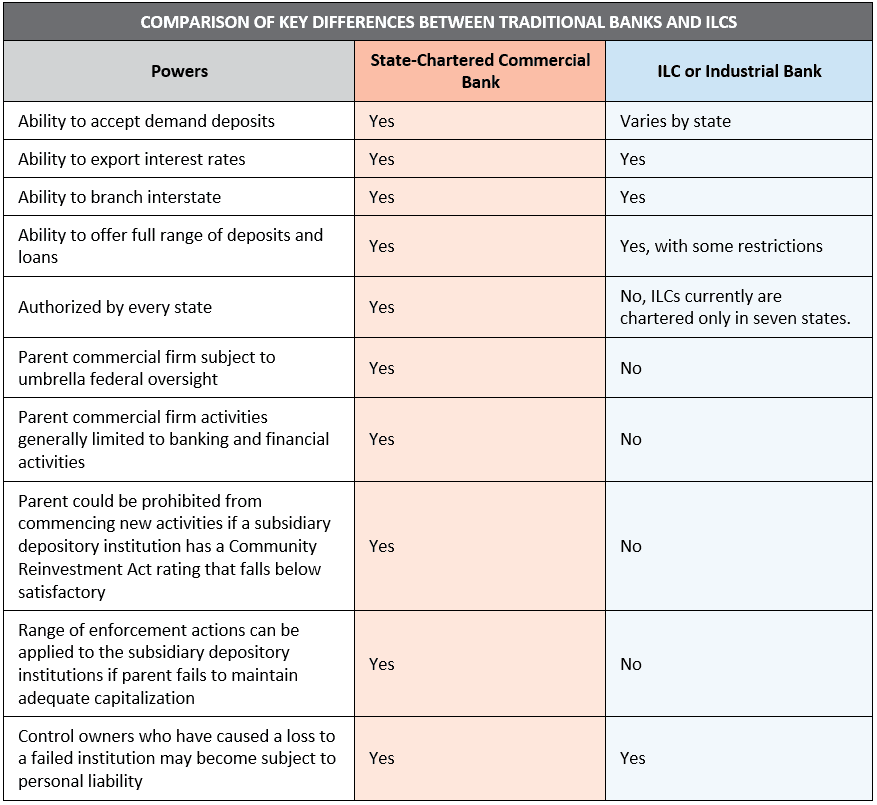

It was two other developments, however, that made ILCs the controversial topic that they are today. The first development is progressive expansion of powers by individual states over the last century. As a result, many ILCs perform activities largely identical to today’s top commercial banks, including in some cases deposit-taking activities, as the table below shows.

Source: Adapted from Lexis Nexis

In addition, ILCs have not necessarily remained small. As the Government Accountability Office (GAO) noted in 2005, “The ILC industry has experienced significant asset growth and has evolved from one-time, small, limited purpose institutions to a diverse industry that includes some of the nation’s largest and more complex financial institutions.” Total assets held by ILCs have grown from $4.2 billion in 1987 to a peak of $213 billion by 2006. Following the FDIC moratorium of 2006 (see below), this number currently stands at $102.4 billion.

It is not inherently concerning for industrial banks to be performing the activities of commercial banks, provided that industrial banks are subject to the same regulation and oversight as commercial banks. This is not the case, however, and follows from the second development, the 1987 Competitive Equality Banking Act. This law identified ILCs as an exception to the rule that all companies that own and control banks be registered as Bank Holding Companies (BHCs). Although this can get a little technical, it has two implications. First, under the normal course of events, only banks can own and control banks. Second, these banks – both the commercial banks and the BHCs – are regulated and supervised by the Federal Reserve Board (the Fed). As a result of the 1987 Competitive Equality Banking Act, ILCs do not have to be owned by banks and are not subject to scrutiny by the Fed.

Fear of the “unique risk” that ILCs thus pose to the safety and soundness of the banking system appears to have led the FDIC not to issue an ILC charter in decades. Nevertheless, controversy surrounding ILCs appears to be relatively new. In 1988, General Motors was granted an ILC charter, closely followed by other firms including BMW, Harley-Davidson, General Electric, and Target, all chartered in either Utah or Nevada. In 2006, however, when Walmart filed an application with the FDIC to be chartered in Utah, there was an enormous outpouring of protest. Two public hearings were held on Walmart’s specific case, and the FDIC enacted a moratorium on new ILC charter applications. Ultimately Walmart withdrew its application before a decision was made, and research by the Milken Institute shows that since this date all states in which ILCs are permitted have passed laws restricting the powers of ILCs.

More recently, similar arguments both for and against expansion of ILC membership have been made following applications in December 2018 by Square, an American fintech firm, and in August 2019 by Rakuten, a Japanese e-commerce company, both of which saw considerable media comment. On March 18, news broke that the FDIC had approved charters for both Square and Nelnet, a student loan servicer. Square announced that it had already achieved charter approval from Utah, but it is believed Nelnet is still waiting for state-level approval.

Conclusions

The proposal is undoubtedly a step in the right direction. Simply codifying existing practices into a regulatory architecture is a desirable goal in and of itself, but the rule goes further by proposing some new requirements, including that a parent company make available a constant pool of capital or access to credit to the bank that it owns.

While these developments are to be welcomed (and unanimity at FDIC only highlights this point), the impact is confined solely to the ILCs that the FDIC already regulates, and this proposal on its face thus does not indicate that any de novo ILC charters would be granted. It was therefore surprising that a day later the FDIC approved two new charters, the first since 2006. Fresh life has been breathed into the viability of ILCs, and this is a series of decisions that fintechs and other firms will be following closely and should lead to an explosion in the number of ILC applications to the FDIC.