Insight

November 24, 2025

Novel Drug and Biologic Development: Impacts of Recent FDA Regulatory Efforts

Executive Summary

- Under its current leadership, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has initiated sweeping reforms intended to optimize the development and approval process of novel drugs and biologics.

- These reforms include updates to translational and clinical research practices, new avenues of communication with therapeutic sponsors, adoption of tools and methods designed to make the agency more efficient, and alignment of FDA operations and regulatory incentives with broader federal health initiatives.

- Although some of the FDA’s recent actions offer promising solutions to long-standing challenges faced by both pharmaceutical sponsors and patients – perhaps driving future biopharmaceutical innovation – the near and long-term success of these actions will likely depend on their proper implementation and potentially confounding impacts of conflicting government priorities.

Introduction

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has recently initiated sweeping reforms intended to optimize the development and approval process of novel drugs and biologics. These endeavors demonstrate current agency leadership’s commitment to address real and perceived regulatory inefficiencies that may have impeded biopharmaceutical innovation and patient access to promising new treatments. Central to this strategy is a series of recent guidance documents and policies designed to update translational and clinical research practices, improve communication between the reviewers and drug and biologic sponsors, bolster the agency’s workload efficiency, and align FDA operations and regulatory incentives with broader federal priorities outside of the agency’s traditional purview, such as reducing prescription drug and biologic prices and onshoring manufacturing facilities. Together, these actions affecting both the speed and basis of FDA decision-making will likely elicit significant disruptions to the tightly regulated and deeply prospective drug and biologic market.

Efforts to update the FDA’s review process are a recognition of challenges facing drug and biologic sponsors. Although the FDA continues to approve novel therapeutics at a steady rate, industry data highlight the substantial resources necessary for marketing success within the current development pipeline. Some estimates suggest that bringing a single product to the market may require an investment of $2.2 billion on average, distributed over the course of more than a decade. These figures, which reflect expensive pharmacologic investigations, as well as high rates of failure at various points in the regulatory process, have led larger firms to acquire promising therapeutic candidates from smaller competitors. Over time, this consolidation may weaken the industry’s collective research and development (R&D) portfolio, as a growing share of the sector focuses on more narrow coveted therapeutic areas – such as anti-obesity medications – instead of pursuing new molecular discoveries.

Ensuring that the cost, time, and risks associated with novel drug and biologic development are sustainable is a key, often overlooked role of the FDA. The predictability of the regulatory environment is a crucial consideration for sponsors when deciding whether to pursue the next therapeutic product. In the past, favorable regulatory conditions have contributed to significant growth in R&D spending, resulting in the biopharmaceutical sector collectively spending more than $100 billion last fiscal year. Although some of the FDA’s recent actions offer promising solutions to several of the unique challenges faced by both drug and biologic sponsors and patients, their near and long-term success will likely depend on proper implementation and potentially confounding impacts of conflicting government priorities.

Trends in Novel Drug and Biologic Approvals

Since the beginning of 2015, the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) and Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) have collectively approved just over 600 novel drug and biologic products for marketing (see Figure 1). These products contain unique active moieties – the component of a drug or biologic that induces its therapeutic effect – that had not previously been approved as any treatment by the FDA. They often address unmet medical needs for patients with rare diseases, including certain genetic conditions, cancers, and autoimmune disorders. Other novel therapies may originate from the need to address emerging public health threats, such as the mRNA vaccines developed during the COVID-19 pandemic.

FDA marketing approval is preceded by many years of costly R&D and regulatory compliance. Much of this time is spent conducting multiple clinical trials, culminating in the sponsor submitting a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics License Application (BLA) to the FDA for a final marketing review. Given the agency’s stringent standards for product safety and efficacy, FDA-approved drugs and biologics are relatively uncommon. Over the past decade, the agency averaged just under 56 novel drug and biologic approvals per year.

Figure 1: Number of Novel NDA/BLAs Approved & Denied by CDER & CBER

Sources: FDA, The Pink Sheet

Over this same period, the FDA issued 157 complete response letters (CRLs) for novel NDA and BLA submissions. These letters, issued to sponsors of unapproved therapies, identify deficiencies that must be resolved before a product can be considered again. Depending on the complexity of these adjustments, as well as the time it takes the FDA to conduct a secondary review, approval may take several months or years to achieve.

The observed decline in NDA/BLA approval rate charted above should not be misconstrued as evidence of systematic failure. Instead, the data highlight moderate volatility in year-over-year approvals amid constantly evolving scientific and regulatory standards. This does not necessarily indicate a flaw in the existing review process, but rather a feature of the FDA’s responsibility to approve only the most clearly beneficial treatments. Understanding the urgent needs of many patients, however, the FDA has continued to evaluate new methods of enabling faster development and approval cycles for certain drugs and biologics that address market shortcomings.

Past Efforts to Change Novel Drug and Biologic Development and Approval

Prior to the enactment of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act (PDUFA) in 1992, almost all NDAs and BLAs underwent a standard review process, with marketing decisions typically made between 21 and 29 months after the application was filed. To address this slow regulatory timeline, PDUFA authorized the FDA to collect user fees from drug and biologic sponsors in order to support an expansion of agency resources, thereby accelerating the decision-making process. As a result, standard reviews today are usually made within just 10 months of application filing. Additionally, PDUFA also authorized the creation of several expedited review pathways, designed to incentivize the development of certain therapeutics by offering even shorter regulatory timelines and sometimes additional benefits. In most cases, eligibility for expedited review pathways is predicated on the therapeutic’s indication for serious, life-threatening conditions and the potential to address unmet medical needs. Drugs and biologics meeting these criteria may earn consideration for one or more expedited review programs — including Fast Track, Breakthrough Therapy, Accelerated Approval, and Priority Review.

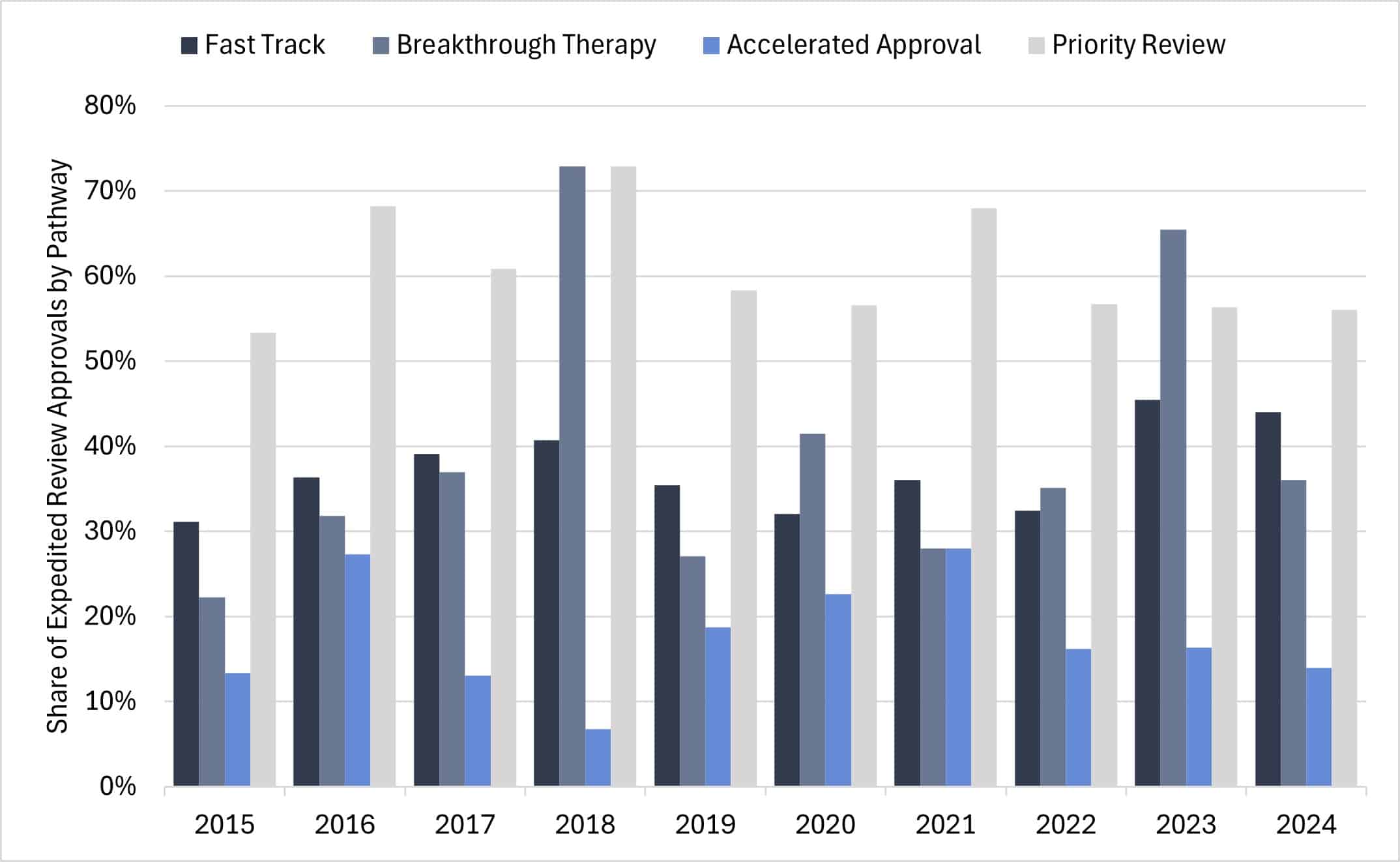

Examining expedited review pathway approvals (only including CDER) for novel drugs and biologics over the past decade indicates most products received designations under multiple pathways. Priority Review remains the most frequently used program, accounting for over half of all expedited approvals each year (see Figure 2). Priority Review shortens FDA market-decision timelines but does not offer additional benefits provided by other pathways. For instance, therapies granted Accelerated Approval may have lower R&D costs by skipping clinical trials, relying instead on surrogate endpoints to support early market access. Likewise, products approved through the Breakthrough Therapy pathway often benefit from shorter development cycles, using intermediate or surrogate endpoints at key points in clinical development. Finally, the Fast Track program enables more frequent communication with the FDA and allows for rolling submission and review of NDA or BLA data.

Figure 2: CDER Expedited Review Approvals by Pathway Designation

Source: FDA

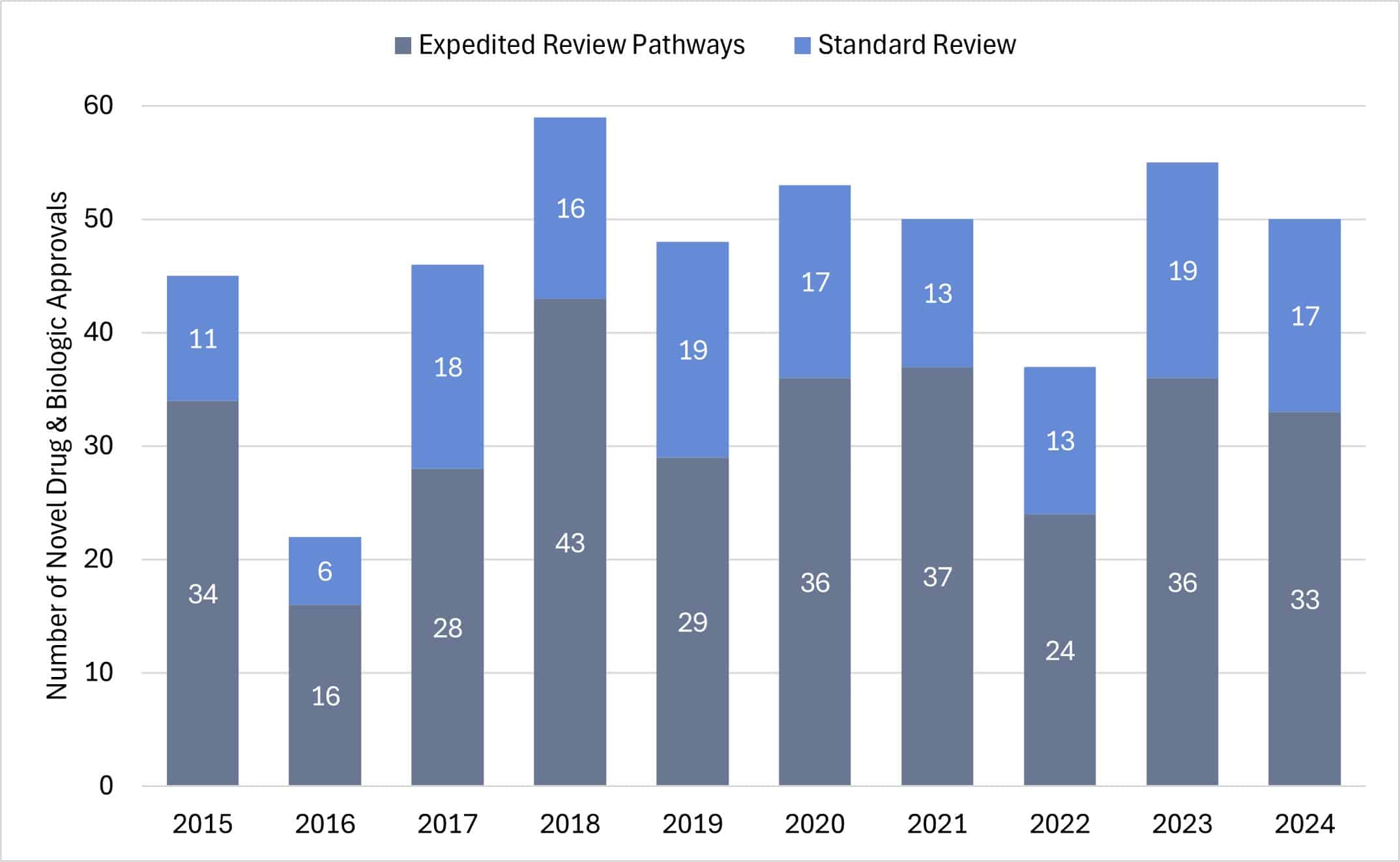

In recent years, novel drugs and biologics approved through expedited review pathways far exceeded those approved under standard review (see Figure 3). This trend demonstrates the impact of PDUFA and its regulatory incentives designed to promote therapeutic innovation in specific, high-priority therapeutic areas. Given that expedited review pathways often remove the scientific modalities necessary for standard reviews, ultimately decreasing the time spent in development, firms may continue to invest heavily in the R&D or acquisition of drugs and biologics indicated for defined high-priority diseases.

Figure 3: CDER Novel Drug and Biologic Approvals by Standard and Expedited Review Pathways

Source: FDA

Despite the success of expedited review programs in expanding treatment options for vulnerable patients, concerns about ethics and scientific integrity persist. Some therapies approved through these pathways have later been found to be unsafe or ineffective. While such cases may be unavoidable, recent studies reveal that available regulatory buffers are often neglected. According to these sources, the Accelerated Approval and Breakthrough Therapy pathways frequently do not enforce postmarket surveillance measures or confirmatory trials for approved therapeutics, a process that is supposed to be mandatory. Current leadership at the FDA has similarly questioned the use of these programs, which may have been the impetus behind recent policies intended to amend the drug and biologic development and approval process.

Recent Updates to the Novel Drug and Biologic Development Process

Earlier this year, FDA Commissioner Martin Makary and CBER Director Vinay Prasad published an article detailing the agency’s new priorities. Key proposals in this manifesto included reforming preclinical testing requirements, expanding and revising review pathways, and fostering more collaborative arrangements between product sponsors and the agency. Many of these goals broaden FDA’s strategic agenda from previous administrations. Since the article was published, the FDA has released a series of guidance documents and codified other changes updating the drug and biologic approval process.

New Molecule Discovery

Novel drug and biologic development begins with the identification of a “target” agent, usually a protein or gene, that is linked to a specific disease. After a target is established, researchers screen thousands of chemical or biologic compounds to find those with promising therapeutic effects on that agent. Molecules that move past the initial vetting process are then retested to produce and identify more potent pharmacokinetic effects. Sponsors may advance one or more “lead” molecules to preclinical testing based on the preliminary results. In total, the discovery stage can take more than four years and account for roughly 30 percent of final R&D cost.

Although the discovery stage occurs before direct FDA oversight, the agency’s guidance applied in later development stages greatly shape the direction of preliminary research. Using this influence, the FDA published draft guidance specifically promoting the discovery of novel non-opioid analgesics by laying out clearer, more predictable development pathways and regulatory incentives. These recommendations – particularly those addressing clinical trial design – aim to reduce uncertainty and help sponsors better assess the likelihood of marketing approval during early development.

More broadly, sponsors tend to align new molecule discovery efforts in therapeutic areas where the FDA provides clear recommendations and opportunities for shortened approval pathways. This may be evident in the recent rise of investigational new drugs – such as monoclonal antibodies and cell and gene therapies – targeting rare diseases, which now benefit from more explicit regulatory incentives. While FDA guidance cannot dictate how sponsors conduct R&D, the perceived benefits can influence upstream novel molecule discovery.

Preclinical Research

After a molecule is selected but before the therapeutic can begin clinical trials in humans, it must first undergo preclinical studies to evaluate its safety, toxicity, and pharmacokinetic properties in other organisms. These assessments are commonly based on evidence collected from tests in animals or in vitro models using human cells or tissues. The cost and duration of this development stage can vary widely and is often associated with relatively high molecule attrition rates. Molecules that show potential clinical benefit – including preliminary biomarkers supporting safe starting doses – may then be considered for clinical trials.

Modernizing preclinical research has become a key area of interest for current FDA leadership, reflecting the agency’s intent to strengthen the reliability of translational studies, while reducing the need for animal testing. In April, the FDA published updated guidance addressing long-standing concerns about the predictive value of animal studies and redundancy of certain testing protocols. The agency’s new recommendations endorse the use of many new approach methods (NAMs) as alternatives to traditional in vivo studies. Specifically, the guidance encourages sponsors to leverage computer modeling and artificial intelligence (AI) or lab-grown human organoids to predict a drug or biologics behavior in humans.

Through NAMs, the FDA aims to modernize scientific standards, streamline preclinical evidence generation, and reduce R&D costs during early-stage development. While NAMs have several notable limitations – particularly the scope of their physiological replication – sponsors continue to invest in their adoption. To promote further implementation, the FDA has also proposed expedited review pathways and other regulatory incentives for sponsors engaging in non-animal testing preclinical studies. Proponents suggest NAMs could enable more ethical, reliable, and cost-effective R&D practices, resulting in greater downstream innovation.

Investigational New Drug Application

Prior to conducting clinical studies, drug and biologic sponsors must submit an investigational new drug (IND) application to the FDA. This submission includes data from preclinical studies – providing evidence on pharmacology and toxicology – in addition to details about clinical trial protocols and manufacturing controls. At this stage, sponsors may also request special designations, which often include expedited review pathways or other benefits.

The IND application stage marks the FDA’s first direct involvement in drug and biologic development and represents a pivotal shift from new molecule discovery to use in humans. Given the high attrition rate of candidates during subsequent clinical trials, the FDA has sought to strengthen IND sponsor alignment with agency standards. Assuming these agency standards reflect the most reliable methods for predicting a drug or biologic’s clinical benefit, stronger alignment could improve review efficiency by preemptively eliminating unsafe or ineffective candidates from the development pipeline.

One area the FDA has focused its IND realignment efforts is cell and gene therapies (CGTs). Specifically, the FDA’s recent draft guidance on the Regenerative Medicine Advanced Therapy (RMAT) designation offers updated recommendations on what methods can be used to provide “preliminary clinical evidence,” which includes support for adaptive clinical trial designs, novel endpoints, and various enrichment strategies. Moreover, the guidance recommends that CGT sponsors engage in frequent communication with CBER review staff during the early stages of development, encouraging more transparency around FDA expectations. Finally, the updated policy clarifies the agency’s recommended use of real-world evidence to support Accelerated Approval when conventional clinical trials and scientific review are not feasible. While together these provisions indicate streamlined development for high-priority therapeutics, current leadership at the FDA has demonstrated restraint in approving CGTs.

Beyond CGTs and technical considerations for IND applications, the FDA has also taken steps to broaden expedited review pathways aligned with less conventional agency priorities. In June, the agency announced the Commissioner’s National Priority Review Voucher (CNPV) Pilot Program, which grants the FDA commissioner the ability to designate therapeutics for shortened review periods. Sponsors can redeem vouchers for any of their products, reducing standard NDA or BLA review times from 10–12 months to as little as 1–2 months. As an added provision, sponsors with CNPVs may receive enhanced communication benefits, which include interim reviews and early feedback throughout the clinical trial process. Thus far, the FDA commissioner has awarded vouchers to 15 recipients, many of whom were selected because of assurances to onshore manufacturing facilities or commitments to effectuate significantly lower prices across one or more products. Although recipients of CNPVs may also be selected if their therapy addresses a public health crisis or unmet medical need, leadership at the FDA have signaled a preference for sponsors that are willing to align with other strategic priorities.

Clinical Trials

Once an IND application is approved by the FDA, sponsors may initiate human clinical trials. Much like preclinical studies, these trials assess a drug or biologic’s safety and effectiveness, but differ significantly in terms of subjects, protocol, and scale. Clinical trials typically occur in three phases, starting with tests of small groups to determine safe dosage, then gradually expanding to evaluate the long-term therapeutic effect of treatments across larger populations. Each phase is closely monitored by the FDA and designed to identify only the most promising candidates for final marketing consideration. Depending on regulatory designations, the clinical trial process can take as long as 8–9 years and account for roughly two-thirds of R&D costs.

Given the high ethical and financial stakes associated with conducting clinical research, the FDA maintains significant oversight throughout the trial process. The agency enforces regulations for Good Clinical Practice, ensuring both the protection of trial participants and the integrity of clinical data collection. As the science behind drugs and biologics evolve, the FDA and other regulatory bodies must frequently amend clinical trial standards to harbor innovation, while also maintaining paramount considerations for patient safety.

In September, the FDA finalized guidance on E6(R3) Good Clinical Practice (GCP), aligned with principles from the International Council for Harmonization, to emphasize clinical trial focus on early-stage quality considerations, risk-based oversight, and greater flexibility in trial design. To put these principles into practice, the guidance also encourages sponsors to implement new digital tools, including AI-driven data monitoring and wearable devices for remote patient observation. These updates to GCP are reflected in other agency guidance, including those targeting novel therapeutics for gastroesophageal reflux disease and malaria. Provisions in E6(R3) aim to streamline drug and biologic development by modernizing GCP mechanisms, in addition to fostering one global standard for all clinical practices.

In November, FDA Commissioner Martin Makary and CBER Director Vinay Prasad authored an article on the agency’s new “plausible mechanism” pathway, which outlines unique principles for evaluating bespoke drugs and biologics. Specifically, the pathway enables qualifying sponsors to submit aggregated clinical data on therapeutic platforms tailored for individual patients, when traditional randomized control trials are not feasible. According to the authors, the FDA will consider “success with several consecutive patients” and “clinical improvement” as a basis for either standard or accelerated approval. Notably, sponsors will be required to establish mechanistic rationale through preclinical testing and historical data. Generally, the FDA plans to extend the plausible mechanism pathway designation to gene-editing biologics indicated for highly debilitating, often fatal conditions; however, the pathway may become available to sponsors of small molecule drugs in the future.

New Drug Applications and Biologics Licensing Agreements

As previously noted, the final regulatory hurdle before initial marketing involves sponsors submitting a New Drug Application (NDA) or Biologics Licensing Agreement (BLA) to either CDER or CBER. Both centers are required to make filing determinations within 60 days of receipt. Successful applications are properly formatted as common technical documents and provide all the requisite information to inform marketing decisions. CDER and CBER may also refuse to file an application if it has clear deficiencies precluding it from a comprehensive review. Sponsors paying user fees typically receive marketing decisions within 10 months of filing; although some sponsors may experience shorter review timelines through expedited review pathways.

To promote transparency, the FDA has published the NDA and BLA filing checklist currently used by both CDER and CBER. Although the Manual of Policies and Procedures (MAPP), which outlines this checklist, had previously been made available to sponsors, the extensive appendix recently made public was not included. By releasing this additional information, the FDA presents a clearer picture of how both centers conduct reviews. The MAPP and its resources also identify common filing issues and ways to address easily correctible application deficiencies, preventing more trivial problems from interrupting and delaying the review process.

Months prior to the MAPP update, the FDA began proactively publishing almost all CRLs – including past actions – on an open-source database. These files demonstrate how reviewers at both CDER and CBER made the decision to refuse acceptance of an NDA or BLA. Although some content remains redacted, the database gives sponsors material insight into the reasons each marketing application was denied. According to leadership at the FDA, these policies aimed at improving agency transparency may help reduce preventable errors and lower review burdens.

Beyond recent actions to enhance transparency, the FDA has moved to improve review efficiency and reduce application backlogs by launching its generative AI tool “Elsa.” The AI – intended to expand operational bandwidth – assists CDER and CBER staff with reviewing clinical trial protocols, screening technical documents, and identifying adverse events after marketing approval. Other digital adoption at the FDA includes new guidance on alternative tools used to assess a drug or biologic manufacturing facility. The guidance enables CDER and CBER to conduct remote or peer-reviewed inspections of manufacturing facilities in lieu of traditional onsite surveys. Together, these policies are designed to modernize FDA review procedures and greatly accelerate regulatory decision-making.

Postmarket Surveillance and Confirmatory Trials

Drugs and biologics approved for public use remain under ongoing regulatory oversight. The FDA establishes best practices for postmarket surveillance on product safety, effectiveness, and efficacy. These periodic evaluations, coordinated with sponsors, are intended to identify potential adverse events that may not have been observed during clinical trials. Products granted marketing approval based on intermediate or surrogate endpoints must first undergo prompt confirmatory studies. Typically, this requires sponsors to conduct at least one randomized controlled trial. If safety concerns arise, regulators may initiate further investigations, mandate label changes, or even order product recalls.

Under current FDA leadership, efforts to modernize postmarket surveillance have centered on rare diseases. Notably, drugs and biologics marked for these indications are inherently more difficult to evaluate, as the low prevalence of many conditions – sometimes affecting mere hundreds of patients – often makes traditional clinical trials impractical, if not impossible.

To address both ethical and scientific concerns, the FDA proposed new Rare Disease Evidence Principles (RDEP), aimed at improving safety and quality assurances. These principles update the review requirements for ultrarare genetic diseases. Sponsors are recommended to conduct one well-controlled clinical study, in addition to providing confirmatory evidence from relevant animal models or real-world evidence. These new assurances are intended to reduce the need for additional confirmatory clinical trials during postmarket surveillance. While RDEP does not explicitly modify surveillance measures, it – along with other plans to adapt review pathways – reflects the FDA’s approach to reducing the regulatory burden of postmarket oversight.

Potential Complications

Recent FDA actions demonstrate a clear commitment to optimizing the development and approval process of novel drugs and biologics. While many of these policies and strategies build on those introduced under previous administrations, others are new approaches intended to address both existing and emerging national health priorities. The CNPV program exemplifies this evolution, leveraging an existing framework to grant FDA officials greater discretion in advancing drugs and biologics aligned with new federal initiatives. By accelerating these objectives, the FDA aims to have more influence in drug and biologic innovation.

It is important to recognize that none of the policies discussed above operates in isolation. While the FDA may characterize them as one-size-fits-all approaches to specific problems in the drug and biologic development pipeline, each policy interacts with both existing frameworks and external market forces. The intersection of these factors poses many challenges for drug and biologic sponsors that require time and resources to recalibrate regulatory compliance. Given the extraordinary rate of new guidance and the magnitude of change, sponsors will have to weigh opportunity costs when considering the significant investments required for developing novel treatments. Industry leaders and investors have recently warned that volatility at the FDA – particularly among its leadership structure – will have negative implications, suggesting the uncertainty “will reduce overall investment in biomedical innovation.”

One major source of industry uncertainty is the FDA’s operational capacity. Earlier this year, the agency underwent extensive personnel changes following government-wide efforts to reduce the federal workforce. While leadership at the FDA claimed to spare employees involved in drug and biologic review, quarterly hiring reports indicate that both CDER and CBER observed sizable net staffing losses since the reduction in force. Several industry experts have expressed concerns about shortages, suggesting that novel drug and biologic development could be adversely affected. These fears have at least partially been realized, as missed PDUFA deadlines increased to 11 percent – up from an average of 4 percent – in Q3 this year.

The FDA’s new AI platform Elsa – intended to streamline regulatory review workflows – has similarly faced scrutiny. While the tool promises a safe approach to accelerate scientific reviews for drug and biologic applications, several sources currently or formerly involved at the FDA have expressed doubts, citing its inability to provide accurate information. Others have even suggested that Elsa can misrepresent or fabricate scientific studies. Although leadership at the FDA has since denied that Elsa can “hallucinate” when used properly, some staffers note that the agency frequently overstate its capabilities. Regardless of Elsa’s functionality, these conflicting reports demonstrate a prominent divide at the FDA, which may cast further uncertainty across the biopharmaceutical industry.

Beyond guidance from the FDA, sponsors involved in drug and biologic development often depend on assurances and incentives from other areas of the federal government. Notably, a significant share of new molecule discoveries and early-stage development activities are at least partially supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), which issues billions of dollars in research grants each year. This funding stream, however, could be reduced by as much as 40 percent, potentially resulting in many independent and small firm researchers being forced out of therapeutic development entirely. One study found that an earlier cut of similar magnitude may have affected more than half of drug approvals over the past two decades. Of course, such an event could significantly undermine promises to expand treatment options for patients.

The above examples provide only a brief analysis of the potential challenges that may impede the intended impact of recent FDA policies. Other considerations should be made about potential sources of uncertainty after a novel drug or biologic is already launched on the market. For instance, sponsors with products approved through the CNPV may experience pushback from prescribing entities that do not trust the FDA’s basis for approval. While these concerns should not discredit all agency efforts to restructure the novel drug and biologic development and approval process, they should be viewed as a source of caution. As noted previously, sponsors involved in developing innovative therapeutics depend on regulatory certainty and functionality to calculate R&D risk. Without these assurances, fewer products make it through the development pipeline, ultimately preventing crucial treatment options for millions of patients.

Conclusion

Under its current leadership, the FDA has initiated a series of guidance documents and policies intended to optimize the development and approval process of novel drugs and biologics. These endeavors are a recognition of several challenges facing both sponsors and patients, including unnecessary or obsolete regulatory hurdles that may have impeded biopharmaceutical innovation and patient access to viable treatments. From the introduction of new approach methods in preclinical testing, to basing initial marketing approvals on plausible mechanisms, the FDA has signaled notable shifts in the novel drug and biologic market. While some of these recent strategies offer promising solutions to the identified challenges, their near and long-term success will likely depend on proper implementation and potentially confounding impacts of conflicting government priorities.