Insight

July 21, 2016

Oh, The Places You’ll Go: Dodd-Frank Edition

In the Dr. Seuss classic, readers learn their path to the future is an optimistic journey. The same vision was outlined by Dodd-Frank’s supporters – a cost-efficient future free of financial market failure. As we approach the sixth anniversary of Dodd-Frank, however, it’s increasingly obvious how much better off we would be and how many better places we could have gone if Dodd-Frank had never come into existence.

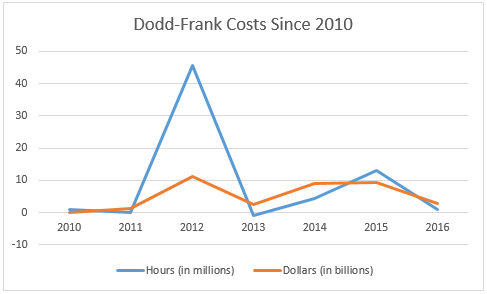

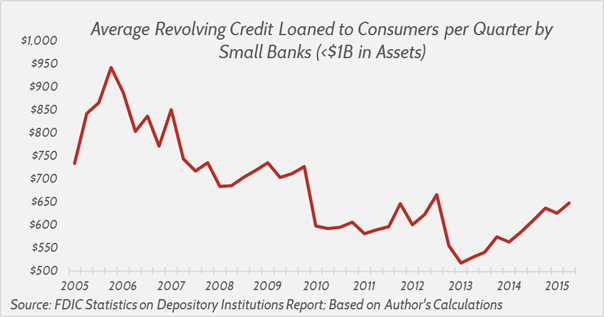

For starters, the availability of consumer revolving credit would be significantly higher. As American Action Forum (AAF) research found earlier this year, Dodd-Frank financial reform has led to a 14.5 percent drop in consumer revolving credit since the law was passed in 2010. As a result, in part, of its $36 billion in final regulatory costs and 74 million hours of paperwork, consumer credit has been one of the most substantially hit victims of the reforms.

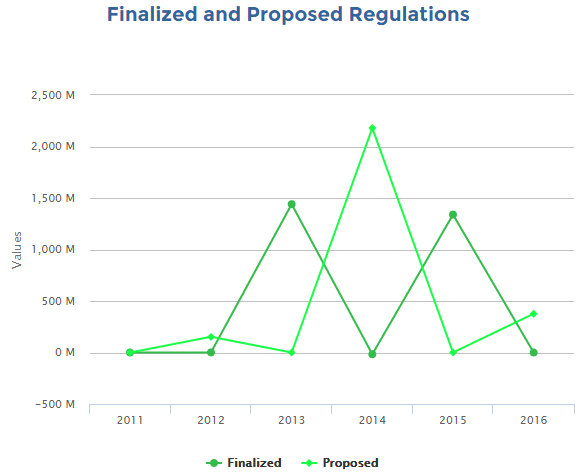

In a recent AAF update on Dodd-Frank, we noted how the Federal Reserve’s (Fed) final rule for “Margin and Capital Requirements,” a product of Dodd-Frank, could cost up to $46 billion with a more conservative estimate of $5.2 billion. The stream of capital, oversight, and reporting requirements has already imposed tens of billion in costs on the U.S. financial system, including small and mid-size banks, despite the authors of the law insisting that the large banks would bear the majority of these costs.

Dodd-Frank’s regulatory burden must be borne by someone, whether by financial institutions and their employees, shareholders, or consumers by way of higher prices and less access to credit. Unfortunately, it appears that the law has affected all three. Further, we know that Dodd-Frank has imposed a regressive impact on smaller financial institutions, has driven up the price of obtaining a mortgage, along with its reduction in average revolving credit loaned to consumers by small banks, as shown in the chart below.

Without Dodd-Frank, we would also be without the Volcker Rule, which was adopted in 2013 by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC), the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), and the Fed, and took effect on July 21, 2015. At its heart, it prohibits banks from engaging in proprietary trading and subjects those banks that do trade to enhanced prudential monitoring by the Fed. It also limits banks’ ownership in hedge and private equity funds. By the government’s own estimates, the Rule will cost banks $4.3 billion. Not only that, Volcker statutorily limits bank’ ability to “make market” by buying selling, and holding inventories in various securities. As banks are forced to shed their market-making operations, customers lose their ability to trade quickly and at a steady price.

Furthermore, now that banks have higher capital requirements, another product of Dodd-Frank, they’re not taking up any excess space holding inventories of assets awaiting a buyer. By way of example, in 2007, JPMorgan carried $2.7 trillion in corporate bonds. By 2015 that number was down to $1.7 trillion and falling. That decrease in liquidity directly hurts consumers, as their options for financial products and services become more limited, and indirectly, as less liquid U.S. banks use their competitiveness abroad – Europe and much of the rest of the world are not restricted by bans on proprietary trading, etc.

Relatedly, it is well documented that as liquidity decreases, the cost of capital for businesses, especially small businesses, decreases. A 2006 Amihud and Mendelson study shows that the level of liquidity (which the study measures as the bid-ask spread on a sample set of securities) affects the anticipated return on those securities and thus the firm’s resulting cost of capital. There is therefore a positive relationship between stocks’ excess monthly returns and bid-ask spreads for any given level of systematic risk. And, as such, average returns are higher for stocks with higher bid-ask spreads, and the increase in the bid-ask spread as a result of the Volcker Rule will result and has resulted in higher capital costs for those businesses, which, of course, results in slower economic growth and reduced job creation.

If we never had Dodd-Frank, we would have never had the Bureau of Consumer Financial Protection (CFPB), the agency created by the law that has thus far burdened consumers with nearly 17 million hours of paperwork requirements and almost $3 billion in regulatory costs.

That doesn’t account for the billions in civil penalties that the Bureau has levied on businesses, many of which resulted from unsubstantiated accusations that were agreed upon under the sole direction of the Bureau’s director, without the oversight of a panel or even the oversight of being dependent on congressional appropriations. (Instead, the CFPB relies on a set, guaranteed fund from the Fed.) If we had never had the CFPB, the taxpayers wouldn’t be footing the bill for the CFPB’s $216 million renovation (which was originally a $40 million proposal back in 2012) of the building it leases, which is valued at $150 million.

Dodd-Frank created another government entity that we could have done without: the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC), which, among other things, is tasked with designating companies as Systemically Important Financial Institutions (SIFIs). Unfortunately for those companies and their customers, these designations can be slapped on businesses that pose no discernable systemic risk to the U.S. economy, like insurance companies MetLife and Prudential. Nevertheless, they are being subjected to intrusive, unnecessary regulation that dries up capital for infrastructure projects and harms investors and policyholders. To make matters worse, FSOC’s process for designating these companies lacks transparency and doesn’t allow companies to work with FSOC to shed their designation.

What does a designation mean for a SIFI? At a minimum, it means increased costs. Since these designations are relatively new, we don’t yet know exactly how high those costs will be, but in the U.S. District Court’s opinion in MetLife v. FSOC, Judge Collyer explains that FSOC “foist[ed] billions of dollars of regulatory costs on MetLife under the auspices of safeguarding it.” And, as a result, MetLife “would have to raise prices and withdraw from certain markets, thereby reducing consumer choice and competition.” For an entity and a designation process that was intended to strengthen companies and increase their ability to withstand a financial crisis, increasing their costs so significantly and forcing them to lose their competitive edge are not the results that anybody wanted.

And the United States isn’t the only place that would be better off had Dodd-Frank never existed. The “conflict minerals rule” is one of the most notorious of the costly regulations to come out of Dodd-Frank. It requires companies to disclose whether they are receiving any “conflict minerals” – coltan, tungsten, tin, and gold – from the conflict zones of, in particular, the Congo. Even though these minerals in the Congo had nothing to do with the crisis, it still cost $4.7 billion and 2.2 million in paperwork hours.

However, the real costs were borne by the Congo. Where possible, firms moved their purchases to other countries’ mines to free themselves of the disclosure requirements, thereby reducing to almost zero the demand from Congo’s mines. In turn, Congo’s government shut down its entire mining industry for six months before proposing a certification process to assure the U.S. that the country’s minerals do not come from “conflict zones.” The delays and politics of the process have all but ended the country’s mining industry. As of October 2011, only 11 of more than 900 mines in South Kivu, Congo, met Dodd-Frank’s standards. Before the law was passed, a kilogram of tin sold for $7, now it sells for $4 even in the certified mines. The Congolese artisanal mining industry employed around 11 million people, most of whom are now being forced to find work elsewhere, which, more often than not, ends up being with an armed militia – the very groups Dodd-Frank’s authors aimed to curtail.

There are many, many more hypothetical situations in which we would be much better off without Dodd-Frank, but perhaps it’s most effective to leave it at this: Without Dodd-Frank, we would have paid $36.2 billion less in total regulatory costs and spent 73,943,194 fewer hours doing government paperwork. That’s an average of $114 and about 15 minutes wasted on Dodd-Frank per U.S. resident.