Insight

May 5, 2023

Pharmacy Benefit Managers: Transparency Measures Aren’t a Silver Bullet

Executive Summary

- In response to rising prescription drug costs the Senate Finance Committee released a bipartisan transparency framework, alongside the Senate Committee on Heath, Education, Labor and Pensions transparency bill language, to require pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) to provide comprehensive information on drug costs, rebates, and patient utilization to plan sponsors.

- These transparency requirements are intended to allow plan sponsors to better investigate the flow of monies in the drug supply chain under the suspicion that PBMs increase patient costs.

- These transparency requirements are unlikely to reduce costs for health plan enrollees and run the risk of inadvertently reducing competition and increasing health care costs by forcing PBMs to comply with costly and time-consuming reporting mandates.

Introduction

In response to rising prescription drug costs, the Senate Finance Committee released a bipartisan transparency framework, and the Senate Committee on Heath, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) published transparency bill language, that would require pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) provide comprehensive drug utilization data on drug costs, rebates, and patient utilization to plan sponsors, typically employers. These requirements are intended to allow plan sponsors to better investigate the flow of monies in the drug supply chain, under the suspicion that PBMs increase patient costs. Nevertheless, these transparency reforms would set expensive reporting requirements in private business contracting that could ultimately undermine the PBM incentive structure, limiting competition and increasing costs.

PBMs are contracted by health plans to provide pharmacy benefits to plan sponsors’ enrollees. They also offer drug formularies to health plans by negotiating rebates from drug manufacturers. PBMs create pharmacy networks, reimburse pharmacies for dispensing and purchasing a drug, and provide utilization management tools such as prior authorization and step therapy. It is important to note that PBMs are third-party administrators who pay pharmacy claims on behalf of the health plan and aren’t hired or even seen by the patient. Rather, PBMs use rebate negotiations with drug manufacturers to reduce the health plans’ overall prescription drug costs, not the cost of an individual patient’s transaction.

PBMs exist at the opaque intersection of health plan services and payments. Legislators at the federal and state levels for years have called for transparency requirements around their rebate negotiations but have mostly focused their efforts on enrollees’ costs at the pharmacy counter for specific medications. States have in the past tried and failed to make PBMs directly accountable to patients outside the scope of their relationship with health plans.

Pharmacy Benefit Managers: Just a Middleman

What are PBMs?

PBMs are third-party administrators that work on behalf of health plans to provide pharmacy benefits to beneficiaries, which includes designing a prescription drug formulary, creating a network of pharmacies for beneficiaries to visit, and reimbursing pharmacies for dispensing and purchasing a drug.

What do they do?

PBMs provide numerous administrative and claims-processing services to health plans, including negotiating rebates with drug manufacturers to manage a drug formulary, creating networks of pharmacies, reimbursing pharmacies for dispensing as well as purchasing a drug, and employing unpopular but cost-saving utilization management tools for health plans, such as prior authorization and step therapy. PBMs may or may not own and operate retail or specialty pharmacies.

What PBM transparency measures is Congress considering?

The Senate Finance Committee released a bipartisan transparency framework following a March hearing on PBMs. This framework aims to delink PBM compensation from drug prices set by manufacturers and enhance price transparency in future legislative text that will presumably provide more detail. Some experts have speculated that the committee will release legislative language to provide specific authority to the Federal Trade Commission to oversee PBM business practices as described in a separate bipartisan package recently reported out of the Senate Commerce Committee.

Additionally, the Senate HELP Committee released transparency bill text on PBMs. The bill would ban spread pricing and require that PBMs remit 100 percent of rebates, fees, alternative discounts and other remuneration from drugmakers, distributors, wholesalers, and rebate aggregators to applicable health plans. It further requires PBMs to report comprehensive data related to drug utilization and other related payment information to plan sponsors on an annual basis. The bill also requires PBMs provide specific information to the Government Accountability Office. The May 2, 2023, hearing ended in an unexpected recess as senators expressed concerns around marking-up the bill prior to the hearing with drug manufacturers and PBMs on insulin costs scheduled for May 10, 2023.

Transparency measures aren’t a silver bullet

Since 2016, PBMs have been at the heart of state-level transparency legislation. Currently, 14 states have passed laws to gain insight into the U.S. prescription drug chain.[1] Although transparency reforms are popular as a bipartisan solution to mitigate drug costs, they do little for individual beneficiaries. For example, the state of Georgia requires PBMs publish specific payment data related to pharmacy pricing. Prime Therapeutics, a PBM, posts this information on its website – an almost 2,000-page report detailing pharmacy reimbursement. Policymakers intended this law to increase public transparency into PBM payments, but it may also have the unintended consequence of, over time, pressuring competing PBMs to align their payment amounts to pharmacies.

PBMs participate in many different complex financial transactions, which can, at times, appear opaque to the health plan, pharmacy, and patient. Yet in mandating that PBMs comply with costly and time-consuming reporting requirements as outlined in these proposals, lawmakers risk increasing costs for plan sponsors – and likely their beneficiaries – as PBMs will likely charge health plans for the costs of such disclosures.

Why are PBM services controversial?

Over the last decade, drug manufacturers have set higher list prices, while increasing the size of the rebates they offer to secure placement on a PBM’s drug formulary, as part of the manufacturer-PBM negotiation process. The surge in rebates, as well as PBM compensation tied to a percentage of rebated dollars, also known as spread pricing, has led to two prominent state investigations (Pennsylvania and Ohio investigations) into PBM profits in Medicaid. Furthermore, New York has carved out PBMs from Medicaid-managed care over concerns of misused rebated compensation.

Some studies have shown that their negotiations may artificially increase drug list prices as the rebate process is fairly arcane, inefficient, and opaque. PBMs are quite profitable (and often benefit from taxpayer money) without producing a drug or caring for a patient. The three largest PBMs (CVS, Express Scripts, and OptumRx) dominate approximately 80 percent of the market and are owned by, or own, a health plan. MedPAC’s 2023 report to Congress on Medicare Payment Policy warns that these large PBMs may have conflicting interests among their integrated entities.

The focus on rebated compensation may be misdirected. One study highlighted that “PBMs pass back…90% of total rebate dollars, regardless of form, received from brand-name pharmaceutical manufacturers.” In managed Medicaid, spread pricing is a payment arrangement to mitigate financial risks to the health plan if its beneficiary pool had an unexpected increase in claims, typically paid via administrative and other service-related fees. In 2019, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued guidance on this practice.

Rebates are not the sole indicator of cost-savings for a plan or reimbursement for a PBM. According to a IQVIA study, 91 percent of the 6.4 billion prescriptions filled in the United States in 2021 were generic drugs.[2] Typically, generic manufacturers do not offer rebates for preferred placement on a PBM’s drug formulary.[3]

Other services performed by PBMs can generate additional fees.[4] To offset rebates that are entirely sent to the health plan, PBMs “have been getting fees from manufacturers that are not strictly called ‘rebates,’ but that still function as de-facto rebates,” as the Advisory Board, a health care consulting firm, observed. As rebates become increasingly controversial, PBMs look to other sources of revenue – including those PBMs that own and operate pharmacies – to increase profits.

What are rebates and how do they relate to beneficiary cost-sharing or savings?

PBMs negotiate rebates with drug manufacturers to reduce the amount a health plan would have to pay for drugs. Rebates are also used by PBMs when creating a drug formulary. Drugs with higher rebates can typically increase market share by receiving a preferred status on a drug formulary over other drugs. PBMs then offer different formularies to health plans to select for their beneficiaries.

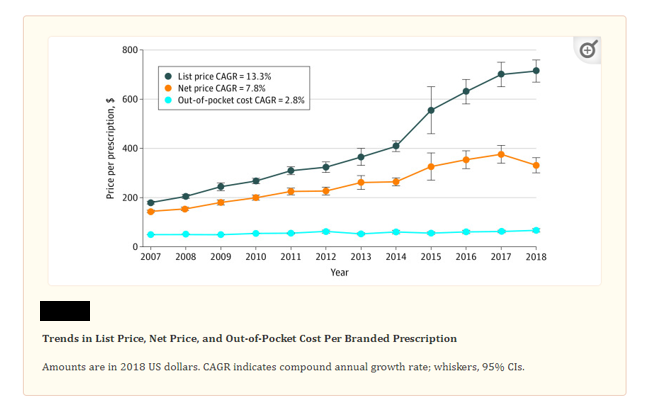

For Medicare Part D beneficiaries, however, some evidence has circulated that PBMs may not consider the individual transaction for a beneficiary based on their cost-sharing as a percentage. [5] CMS found that “Higher point-of-sale prices generally result in higher beneficiary cost-sharing obligations as cost-sharing is often assessed as a percentage of the list price. For example, if a beneficiary’s cost-sharing obligation is 10 percent out-of-pocket, a beneficiary will need to pay $10 for a drug with a list price of $100, as opposed to $5 for a drug with a list price of $50.”[6] Yet the PBM may prefer the high-cost drug, as the rebate to the health plan is more beneficial to the pool of covered beneficiaries as compared to limited transactions when the beneficiary may pay a slightly larger coinsurance. One study found that beneficiaries’ out-of-pocket costs have remained statistically similar since 2007, with an increase in out-of-pocket costs of $4 for branded drugs between 2007–2013 and $11 per branded drugs between 2014–2018. (see chart, below)

Kai Yeung, Stacie B. Dusetzina, and Anirban Basu “Association of Branded Prescription Drug Rebate Size and Patient Out-of-Pocket Costs in a Nationally Representative Sample, 2007-2018” JAMA Network Open. 2021 Jun; 4(6): e2113393.

Yet not all drugs have rebates, and according to a recent study, “rebates as a percentage of total spending increased from 22 percent to 24 percent for brand drugs, while for specialty drugs it increased from 10 percent to 13 percent between 2017 and 2019.” Notably, the study found that while total pharmacy spending increased, overall rebates received by health plans from the PBM saved the plan money.[7]

Maine PBM Reform and Repeal

In June 2011, Maine’s legislature repealed a costly 2003 state law[8] that mandated “fiduciary-disclosure requirements on PBMs…the law had forced all employers into a mandated state-prescribed contracting model for pharmacy benefits.”[9] Following the enactment of the law, PBMs left the state, citing a poor business climate. PBMs’ exit from the state market resulted in projected higher drug costs and less competition, leading Maine lawmakers to reverse course.

Furthermore, most states rejected similar laws since the enactment of the Maine legislation, citing increased costs and little benefit for patients. In place of these fiduciary laws, most states have amended their statutes to required PBMs act in “good faith and fair dealing.”[10] In 2022, New York extended this requirement to patients.[11]

Conclusion

PBMs exist at the opaque intersection of health plan services and payments. Their unclear business practices, concentration in the market, and the nature of their reliance on rebates often draw scrutiny. But the Senate Finance Committee transparency bipartisan framework and HELP transparency bill may ultimately undermine the PBM incentive structure and set precedents in private business contracting that limit competition and increase costs.

[1] National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP), Drug Price Transparency Laws Position States to Impact Drug Prices. According to NASHP “Vermont passed the first state drug price transparency law in 2016. Since then, 13 other states have passed transparency laws focused on drug manufacturers and other actors within the supply chain — CA, CT, ME, MN, NV, NH, ND, OR, TX, UT, VA, WA, and WV. Most state programs require reporting from manufacturers when they increase the wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) of a drug above a certain threshold or if they introduce a drug with a high launch price. Several states also require reporting from insurers and pharmacy benefit managers.”

[2] Association for Accessible Medicines “The U.S. Generic & Biosimilar Medicines Savings Report.” 2022.

[3] American Health Law Association “The Role of Rebates in the Pharmaceutical Industry” July 30, 2021. The authors explain that “Generic manufacturers do not typically enter into supply agreements with PBMs (apart from PBM-run mail-order operations). Instead, they generally negotiate pricing with the companies that stock their products, such as retail pharmacies and generic source programs (a generic drug one-stop-shop alternative for independent pharmacies run by wholesalers like McKesson).”

[4] For example, UnitedHealth Group reported in their 2022 10-K report that OptumRx managed “$124 billion in pharmaceutical spending, including $52 billion in specialty pharmaceutical spending” and “total manufacturer rebates receivable…amounted to $8.2 billion” in 2022. PBMs do not profit only from rebates but from a variety of services they offer for health plans.

[5] Elizabeth Plummer et al “Trends of Prescription Drug Manufacturer Rebates in Commercial Health Insurance Plans, 2015-2019.” JAMA Health Forum. The authors found that “While drug rebates can reduce plans’ net costs, rebates do not reduce patients’ cost sharing, which is usually based on prerebate list prices set by drug companies.Drug rebates can incentivize drug manufacturers to inflate list prices and PBMs to distort drug formularies to favor high list price and high rebate therapies.”

[6] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, “Medicare Part D – Direct and Indirect Remuneration (DIR)” 2017.

[7] Center for Improving Value in Health Care “Drug Rebates Impact Rising Prescription Drug Spending and Continue to Increase for High Cost Drugs Like Brand and Specialty.” CIVHC found that “In the analysis of 2017-2019 drug rebate information submitted to CIVHC by health insurance payers in the state, total pharmacy spending increased from $3.8B to $4.4B, or 14%, without rebates. However, when factoring in rebates received back by payers through their Pharmacy Benefit Managers, pharmacy spending increased 11% ($2.9B to $3.2B), indicating that drug rebates are helpful in reducing overall spending.”

[8] L.D. 554 (2003) or An Act To Protect Against Unfair Prescriptive Drug Practices.

[9] PBMs are typically not considered fiduciaries under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA).

[10] Nev. Rev. Stat. § 683A.178; CA Bus & Prof Code § 4441 (2021)

[11] N.Y. Pub. Health Law § 280-a